Valeriote was so offended by the modern tabernacle he persuaded Our Lady Immaculate pastor Msgr. John H. Newstead to dust off the old one and take it to a locksmith for repairs. To get at the twisted, dysfunctional lock, the locksmith had to unscrew a plate from the inside of the the tabernacle door while Valeriote and Newstead watched. There on the inside of the plate, where only God could see it, were the names of local Irish farmers who long ago had combined their savings to buy and install the tabernacle.

While The Catholic Register has not been permitted to disassemble the tabernacle, it seems very likely the name Collins is inscribed there. The Collins family arrived in Guelph in 1832, homesteading on Puslinch Lake. They were citizens of Guelph just four years after John Galt and the Canada Company established the town.

Thomas Collins is the first bishop to ever emerge from Guelph, the first archbishop ever born in Guelph and now the first cardinal elector to have called Guelph home. He is as humble, modest and self-effacing as any of Guelph’s 19th-century homesteading Irish farmers.

As a youngster, Thomas Collins was curious about everything, says older sister Cathy. He taught himself to read before entering Grade 1.

Photo courtesy of the Collins family

The Collins family has always been in Guelph, but now all of Guelph is paying attention. The Guelph Mercury will send a reporter to Rome to cover the Feb. 18 consistory where Collins will be made a cardinal. Mercury managing editor Phil Andrews considers Collins more than just newsworthy.

“It’s incredibly significant. He’s incredibly well known and appreciated,” said Andrews. “He has gone to lengths to maintain contact with Guelph.”

Over the years Guelph has produced Olympic athletes and Stanley Cup winners, but nothing really compares with a cardinal, according to Andrews.

When Our Lady Immaculate pastor Fr. Dennis Noon announced Collins would be made a cardinal the congregation broke into spontaneous applause at all three Masses.

Collins said his first Mass in 1973 at Our Lady Immaculate Church. He served there as an altar boy in the 1960s.

Collins said his first Mass in 1973 at Our Lady Immaculate Church. He served there as an altar boy in the 1960s.

When Collins was first made a bishop and sent north of Edmonton to the vast, sparsely populated diocese of St. Paul, he granted an interview to the little weekly paper in Guelph. The Guelph Tribune reporter asked him about the honour and awesome responsibility. He tried to explain how he was only doing what Pope John Paul II had asked of him.

“It’s very exciting, this whole thing of obedience,” he said.

This whole thing of obedience is indeed the whole thing for Thomas Christopher Collins. This is a man whose goal in life was to be a priest — to stand with the people of God in the unbroken line of Christ’s Church.

“I really love being a priest and always have. It’s a real joy,” he told the Tribune in 1997.

It’s clear he regards being a cardinal as more of the same. During a recent visit to his home town, he told a Rotary Club audience about the stages of his vocation.

“The call of God comes deep from the heart,” Collins said. “The call to be a bishop comes by telephone. I got the call to be a cardinal over a BlackBerry.”

Nobody is surprised he got that call. Ever since Pope John Paul II plucked him out of St. Peter’s Seminary to be a bishop Collins has displayed very definite ideas about what a bishop should be and do. By the time he reached Toronto he was on a path.

Pope Benedict XVI was clearly relying on him as he appointed Collins apostolic visitor to Ireland in 2010, brought him to the 2010 synod on the Middle East, appointed him in 2011 to the International Commission on English in the Liturgy and made him the official delegate for Canada responsible for implementing Anglicanorum Coetibus.

Of course, it is a lie that modesty and humility are the opposite of ambition. Collins managed a master’s in English literature from the University of Western Ontario at the same time he was studying for the priesthood at St. Peter’s Seminary in London, Ont. That’s ambition. His doctoral dissertation at Rome’s Pontifical Gregorian University, “Apocalypse 22:6-21 as the Focal Point of Moral Teaching and Exhortation in the Apocalypse,” ran to 732 pages — more than 700 pages on 15 verses of Scripture. That’s more ambition.

Of course, it is a lie that modesty and humility are the opposite of ambition. Collins managed a master’s in English literature from the University of Western Ontario at the same time he was studying for the priesthood at St. Peter’s Seminary in London, Ont. That’s ambition. His doctoral dissertation at Rome’s Pontifical Gregorian University, “Apocalypse 22:6-21 as the Focal Point of Moral Teaching and Exhortation in the Apocalypse,” ran to 732 pages — more than 700 pages on 15 verses of Scripture. That’s more ambition.

If Collins’ highest ambition was for priesthood, his priesthood is also his dearest, most precious possession. His clear, unequivocal response to clerical sexual abuse makes the point.

“People expect that one who is consecrated with the holy oil of Chrism will act in an exemplary manner and never betray the trust which people know they should be able to place in a Catholic priest,” Collins told the faithful at St. Michael’s Cathedral April 18, 2010. “And yet, to our shame, some have used the awesome gift of the holy priesthood for base, personal gratification, betraying the innocent and devastating their lives.”

That bitter sermon full of steadfast resolve was posted on the archdiocese of Toronto web site and distributed in every parish bulletin in the archdiocese. Collins clearly felt the betrayal of abusive priests personally.

He announced new norms for handling abuse cases in the archdiocese. But his initiative went beyond legal and administrative procedures. Collins also let it be known Catholics would not indulge in self-pity, would not blame the media or minimize the damage done.

“We should always be thankful when wrongdoing is revealed, for that can lead to renewal, but in the face of this constant criticism, Catholic clergy and lay people alike can feel discouraged, angry, confused and ashamed,” he said.

While priests who abuse are the exception and not the measure of the Church or its ministry, that does not excuse the whole Church from repentance — repentance that begins with setting things right for victims. From the beginning, Collins linked his reforms to the Pope’s agenda. If obedience is an exciting thing, sometimes it is also hard.

While it might have been a bit of Vatican PR to appoint bishops of Irish descent to the apostolic visitation to Ireland, there can be no doubt that Collins was chosen for reasons deeper than a 180-year-old connection to the Emerald Isle. The Pope and his advisors clearly saw a bishop who understood the spiritual dimensions of the abuse crisis and was prepared to confront it.

The investigation into a culture of cover-up in the Irish Church is an assignment that speaks volumes about who Collins has grown to become. It is a difficult, delicate assignment which begins with the care of souls — souls who may no longer love or trust the Church. He has undertaken it in direct and generous response to the Pope and for the sake of the universal Church.

It won’t be Collins’ name on the report or the recommendations in the final report that will go in confidence to the Pope. He will provide his best insights and if his recommendations are accepted they will belong to the whole Church and Collins will slip into the background.

During seven-plus years as archbishop of Edmonton, Collins demonstrated a style of leadership that had very little to do with pride of office or ostentation.

“He is uninterested in the trappings of high office. It’s not his taste. It’s totally not him,” Basilian Father Timothy Scott of St. Joseph’s College in Edmonton told The Catholic Register when Collins was appointed to Toronto.

It was Edmonton where Collins first launched monthly lectio divina sessions at St. Joseph’s Cathedral Basilica. He showed what the new evangelization might look like when he rented a former Eddie Bauer store in Edmonton’s City Centre Mall and turned it into St. Benedict’s Chapel, a base for ministry to downtown shoppers and office workers.

“He’s a man of initiative. He’s got a great vision of things and he’s got a great love of the Church, and a great love of the priesthood, and a great love of the people,” said archdiocese of Edmonton chancellor Fr. Gregory Bittman.

Collins, who spent almost a decade in Alberta, estimated he might have spoken directly with the province’s premier twice. He doesn’t see himself as a power broker. But that doesn’t mean that he has shied away from public life.

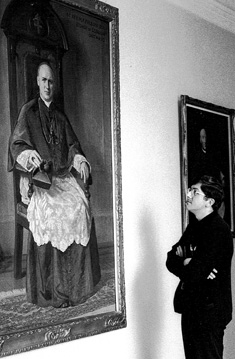

Then-Fr. Collins stands in front of a large painting of Bishop Michael Francis Fallon, the bishop of London who founded St. Peter’s Seminary back in 1912. Little did Collins know he would follow Fallon’s path to the episcopacy.

- Photo courtesy of St. Peter's Seminary

Growing up in Guelph, Collins was quiet, studious and right at the heart of life in his city. He grew up on Durham Street, a couple hundred metres down the hill from Our Lady Immaculate Church. His dad, George, was circulation manager for the Guelph Mercury. His Uncle Joe was city editor at the Mercury.

In those days virtually every household in the Royal City got the local daily. It bound the community together, gave them something to talk about, gave them an identity. All the Collins kids had paper routes. When other kids went on vacation, they had multiple paper routes.

As a student at St. Stanislaw’s Elementary School, Collins walked up the hill on dim wintery mornings to serve Mass. His house faced the back of the church, where a statue of St. Michael is tucked into an alcove and looks down the hill.

There was more to it than early morning deliveries and early morning Masses. Being connected to the paper and the church made the Collins’ kids connected to everything.

Older sister Cathy remembers how curious and persistent Thomas was even before he began school. Seven years older, she was his afternoon baby-sitter before Mom and Dad came home from work. Some days it felt like she spent all day answering questions. The boy taught himself to read before he began Grade 1.

Collins’ first attempt to advance in the Church was thwarted by John Marrin, the formidable choir master, organist and music director at Our Lady Immaculate. Marrin excluded Collins from the boys’ choir because he couldn’t seem to generate any meaningful volume. More than 50 years later, Cathy Collins finds the idea her brother wasn’t loud enough a bit amusing.

“You hear that booming voice when he sings at Mass,” she points out.

The whole family knew he was the smart one, said Cathy, who herself went on to a career as a teacher and school principal. They knew he would go far on the strength of his intellect. But they didn’t know how far he would rise in the Church, she said. There’s more than intellect involved in a priestly vocation.

The 1960s have been burned into our collective memory by the social, political and cultural upheaval caused by the baby-boom generation coming of age and demanding change. It started on big-city university campuses in Paris, New York and San Fransisco but eventually it seemed the whole world was crying out for a new order. The ’60s were supposed to be a clean break from tradition, authority and easy assumptions about right and wrong.

But it was a different sort of ’60s in Guelph.

“We might have been a bit insulated,” concedes Cathy Collins. “I don’t think we experienced any major upheavals in values. We were a fairly stable community.”

The University of Guelph was still an agricultural college. Guelph was a town connected to surrounding farm families. There were good jobs in small factories — everything from the Biltmore Hat factory to Imperial Tobacco. Mothers stayed home. Fathers went to work early and came home to read the Mercury before dinner.

The Collins’ siblings, Cathy, seated, Thomas and Patricia.

Photo courtesy of the Collins family

Faith, family, community pride and stability cocooned Guelph, even as Toronto’s Yorkville was filling up with American draft dodgers, hippies and folk musicians. Schools and churches anchored Guelph. These institutions, so central in Collins’ life, expressed the collective will of the city’s mothers and fathers to protect and nurture their families.

Collins fit right in. He developed an interest in photography, collected stamps and took guitar lessons. His first job was as a car-hop in a drive-in burger joint. He went on to work serving tables at the Jesuit philosophy college on the northern edge of the city. He worked his way through university at a fibreglass plant and on a grave-digging crew at Guelph’s Catholic cemetery.

Cathy believes the cemetery gig helped her brother in his later career.

“It stood him well because when he became a priest he knew the risky places to stand,” she said.

In high school, Collins had a thrilling and impressive English teacher. The young, dynamic Fr. Newstead could sweep into class and recite whole blocks of Macbeth with the book closed in his hand. Newstead had a feel for the power and beauty of language. He could persuade a classroom full of teenagers to apply their minds and hearts to ideas that Shakespeare embodied in characters.

Newstead loved to make summer trips to Stratford for the Shakespeare festival. He loved to talk politics and its underlying truths in history. He was not a priest who feared or rejected the world. Newstead was a man of his times, deeply interested in people and events.

The young Collins was already nursing the notion of a vocation when Newstead gave him a little push.

“He’s forever grateful to Msgr. Newstead. He asked him, ‘Tom, why don’t you consider becoming a priest?’ ” recalled Cathy. “That sort of solidified his thinking.”

Difficult concepts seemed to always come easy to Collins. His seminary brothers often looked his way when trying to decipher difficult concepts.

Photo by Michael Swan

Knowing how they valued academic excellence, the Jesuits attracted Collins’ attention. But in the end he was drawn to the spirituality of the diocesan priest — rooted in a sense of place, a feeling for home and a drive to nurture and encourage a community of families.

While Jesuits are determinedly itinerant — vowing to go anywhere the Pope asks — Collins wanted his life planted firmly somewhere he could call home. His home address remained Guelph until he was 50 years old, when he was ordained in 1997 as a bishop for the diocese of St. Paul.

The career path from associate pastor through high school English teacher to professor of Scripture and rector of St. Peter’s Seminary, bishop and archbishop was never some scheme to rise in the Church. It was an ambition to serve. But the ambition isn’t solely his. Strangely, his elevation to the College of Cardinals fulfills a dream Guelph’s founders had for the city.

“The Catholic world as well as the rest of the world doesn’t recognize the significance of Catholic history in Guelph,” insists

Gill Stelter, University of Guelph emeritus professor of history.

“It’s quite astounding.”

The first cardinal from Guelph was supposed to be Cardinal Thomas Weld, a British Catholic nobleman elevated to the purple in 1830. It was all part of John Galt’s vision of Guelph as an important city. Weld was willing to relocate, but he was made a cardinal by Pope Pius VIII and died in Rome in 1837.

The first cardinal from Guelph was supposed to be Cardinal Thomas Weld, a British Catholic nobleman elevated to the purple in 1830. It was all part of John Galt’s vision of Guelph as an important city. Weld was willing to relocate, but he was made a cardinal by Pope Pius VIII and died in Rome in 1837.

Galt was a Scottish novelist, biographer of Lord Byron and entrepreneur. He was secretary (in modern terms, chairman and CEO) of the Canada Company. The Canada Company made money selling land it got for almost nothing to Irish and Scottish farmers. For farming to be viable, the Canada Company needed a city to anchor the local economy — a market for farm goods and a hub for agricultural services.

But Galt’s vision went beyond functional economics. Churches were needed to civilize the place — not just in the sense of good manners and respect for the law, but to proclaim a certain dignity, to stand up and call people to their better selves.

“A town without a spire is like a face without a nose,” Galt wrote.

To that end, he wanted a bishop in Guelph.

Galt annoyed the British, Protestant establishment of Upper Canada’s Family Compact by granting Catholics the most prominent piece of land in the whole region for their church. This was 1827, when it was still illegal to be Catholic in England. Catholicism was mostly tolerated in the colonies, but in the eyes of Anglican Bishop John Strachan and his circle of business friends known as the Family Compact, that didn’t mean you had to give the Catholics choice real estate.

Somehow Galt, a lowland, Protestant Scot, had struck up a friendship with Bishop Alexander Macdonell, a highland Catholic Scot. The alliance encouraged Galt to dream big. When the land for the Catholic church was set aside, Galt wrote of one day building a cathedral that would rival St. Peter’s in Rome. That may have been fanciful, but in 1852, when the town was 25 years old, Austrian Jesuit John Holzer was appointed pastor of the parish that would eventually become Our Lady Immaculate Church.

Though the Church of Our Lady Immaculate was consecrated in 1888, its towers were added by other architects in another style in 1926. Meanwhile north of the city another sort of Catholic ambition was shaping up on 240 hectares of farm land. The Jesuits established a novitiate for English-speaking Canada there in 1913. By 1958, when Collins was 11 years old, the Jesuit presence had grown into Ignatius College, incorporating both a novitiate and philosophate.

Stetler believes Collins stands in the line of those visionary founders of Guelph, Our Lady Immaculate and the Jesuit project.

“These guys are the tradition Collins represents,” said Stetler. “They were visionaries. He stands in a great line of visionaries.”

Collins wants people to experience the love of God that so often eludes us.

- Photo by Michael Swan

Collins is conscious of his history. Stelter gives Collins credit for the best history yet written about Our Lady Immaculate — a little book published more than 20 years ago, now out of print. History was always one of Collins’ favourite subjects, said his sister.

For Collins, being Catholic is about finding yourself a little bit outside looking in on the flow of history — tethered to the past by tradition and yearning for an ultimate future promised in Scripture. “We are an analogue people in a digital world,” he told The Catholic Register in July 2011.

There’s more to the history that produced Collins than just ambitions of church men. Guelph was also the birthplace of Canada’s Communist Party. That isn’t to suggest the Pope has set aside a gold ring and a red hat for a Bolshevek. But if it’s tempting to think of Guelph as a sleepy backwater where nothing happens, it’s good to remember that Collins’ home town has a knack for finding itself in the middle of the great, passionate debates of history.

Collins’ uncle Joe Downey, in addition to his career as a newspaperman, was a Conservative Member of Provincial Parliament for Wellington South. His grandfather George Keen was a key figure in the co-operative movement in Canada — helping to establish grain co-ops out west and fishing co-ops in Atlantic Canada.

“In terms of skills and even appearance, I think my brother most resembles (Keen),” said Cathy. “He was a very intelligent man, very learned, a person who has read a lot of books.”

Keen was awarded an honorary doctorate by St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, N.S. Without him the Antigonish Movement might have been more a theory than a practical attempt to re-orient the economics of the 20th century.

It comes as no surprise there’s a little politics in Collins’ background. When things began unravelling at the Toronto Catholic District School Board in 2008, Collins stepped decisively into the political arena. He did not speak softly or seek the hush of back-room meetings. Elected officials to a body with Catholic responsibilities were found to have used public funds for private purposes. The archbishop spoke up publicly.

“We believe that the largest Catholic school board in the country has experienced a leadership crisis and consequences are required,” he told The Toronto Star.

Politics is only part of how the Church is engaged in the world. In Toronto, home to refugees from around the world, Collins has sought to make the archdiocese more effective in reaching out and helping people whose lives and homelands have been stolen from them by defective politics. He established the Office for Refugees in 2008. In 2010 he began the process to sponsor an Iraqi refugee family — inspiring dozens of parishes across the archdiocese to set up refugee sponsorship committees of their own.

A scholars’ life has suited Collins well. He spent two decades guiding young seminarians.

Photo courtesy of the archdiocese of Toronto

For Collins, politics are neither beneath the dignity of his office nor too far removed from ecclesiastical expertise. As a cardinal, Collins intends to continue to be heard by politicians about political responsibilities.

“We don’t choose a party. But I intend to speak out on the moral issues in society,” he said after his appointment to the College of Cardinals was made public on Jan. 6.

Nor is it surprising Collins was so forceful when the subject was education. This is a man whose first response to the world has always been to study it. He is the brother, the grandson and the great-grandson of school principals.

“We couldn’t help but talk about education (around the dinner table),” said his sister.

Following in the footsteps of Newstead, as a young priest Collins taught high school English.

The right words in the right place were Collins’ first love. Anyone who has listened to him preach has also heard the man call up stretches of poetry from memory. It’s more than a trick he learned from Msgr. Newstead. Collins believes there are words worth holding in our hearts. He pronounces them in order to place them in the hearts of his hearers.

The right words in the right place were Collins’ first love. Anyone who has listened to him preach has also heard the man call up stretches of poetry from memory. It’s more than a trick he learned from Msgr. Newstead. Collins believes there are words worth holding in our hearts. He pronounces them in order to place them in the hearts of his hearers.

Studying Old English at Western, Collins was so adept at the language his professor had him record language lab tapes so other students would have the sound of Beowulf in their heads.

Fr. Dennis Noon was a year behind Collins in the seminary. Now the pastor at Our Lady Immaculate, Noon recalls how his seminary brothers would turn to Collins for a clear, plain English explanation of often abstruse concepts shovelled at them in convoluted, latinate language during theology classes. Everybody knew Collins understood the complicated philosophical terminology, but they admired him for his ability to make it human and make it real.

“Collins’ biggest attribute, I always thought, was his humility,” Noon said.

That’s still who he is, and it’s because he grew up in small town Guelph, said Valeriote.

“It’s how he talks to people. He’s a very down-to-earth person. He speaks the common dialect,” Valeriote said. “You know he is academically right up there.”

Noon still remembers the talk he had with the seminary rector at St. Peter’s shortly before graduation. It was a chance for Noon to tell the rector (and thereby get word to the bishop) about his successes and frustrations in the seminary, and what they might indicate about his future ministry. But the two of them got onto the topic of Tom Collins.

“I’ve taught here for 46 years and he’s the smartest person I’ve ever taught,” said Fr. Jim Carrigan.

Collins’ first sojourn in Rome at the Pontifical Biblical Institute taught him about the deeper meanings and uses of scholarship. He graduated with more than a licentiate. There he experienced the role of the scholar in the Church.

For Collins, the Christian life must be focussed on simple, direct, human experience of God in our lives.

Photo courtesy of the archdiocese of Toronto

The scholar’s life was something that suited him well. He thoroughly enjoyed his 20 years of teaching and guiding young seminarians. The relative asceticism of his life in Toronto is based in part on that scholar’s instinct for paring things down to allow more scope for study.

How pared down? When he moved from Edmonton to Toronto he declined offers to help him find a suitable house. He took up residence in a small apartment at St. Michael’s Cathedral. And he has remained there.

The apartment is so small there is no room for his cat, Frodo. His sisters, Cathy and Patricia, have adopted the cat, though they are deferential to the idea Frodo belongs to their brother. Frodo has no comment.

The simplicity of Collins’ life isn’t just scholarly. For Collins, the Christian life must be focussed on simple, direct, human experience of God in our lives. The more electronic noise we introduce into our days the harder it is to hear the call of the divine. One of Collins’ favourite prayers is from the First Book of Samuel — “Speak, Lord, for your servant is listening.”

To make that point, Collins instituted a propaedeutic year for his seminarians. It’s a year in which men working toward priesthood have minimal contact with the Internet, e-mail, social media, television, even newspapers.

“Sometimes when you’re studying about Jesus all the time, you’re writing exams on Jesus and all that, you may never stop to think, do I give my heart to Jesus? And do I give my whole life to Him?” Collins said when the program launched last summer.

Collins has thought long and hard about how technology has formed the modern consciousness, but not out of fear. He loves his BlackBerry. It’s said to be loaded with apps. He loves gadgets. He speaks often about how we need to see technology as a tool, rather than allowing technology to direct our actions.

Collins leads people through vespers and lectio divina once a month at Toronto's St. Michael’s Cathedral.

- Photo by Michael Swan

As he leads people through vespers and lectio divina once a month at St. Michael’s Cathedral, it’s clear Collins wants people to experience that single-minded, single-hearted love of God that so often eludes us. He tells people as often as he can that prayer begins with knowing that God is God and I am not.

Once you know who God is you’re ready to be human. In his book about lectio divina, or prayerful reading of the Bible, Collins urges people to experience the holiness of being God’s creature by reading Scripture aloud and then stepping back into silence to feel the weight of the words.

“We can become so abstract, so virtual; using our bodies to speak aloud and hear the words is a way to become more fully human again,” he urges readers of Pathways to our Hearts.

The point of the whole exercise is that “We seek to be humbly attentive to God’s holy Word,” Collins writes. And by “God’s holy Word” he means much more than words on a page. He means the Word that was made flesh, the Word that calls us over and over to the simple truth of God alive and present in our world, in our lives.