Indeed, the first bishop of Toronto, Michael Power, was criticized for building the magnificent and permanent symbol of Catholicism in Toronto too far from the hustle-and-bustle areas of the city’s early years.

Instead, Bishop Power thought the ideal location was an old colonial estate once belonging to a high-ranking administrator in York and prominent Protestant named Captain John McGill of the Queen’s Rangers. McGill received 7,500 acres in land grants and he gave this particular farmland to his nephew, Peter McGill. Bishop Power paid the nephew 1,800 pounds, including money from his own savings, to acquire a plot of land in early 1845. Most of the estate was farmland, some of which had not yet been cleared of trees and forest, hence the nickname “St. Michael’s in the Fields.”

“Bishop Power was a visionary who knew this is where he wanted his cathedral because this would be the very heart of the city,” said Fr. Michael Busch, St. Michael’s rector.

Almost 175 years later as the cathedral re-emerges in much of its original form, it’s difficult to imagine it located elsewhere.

Mayor John Tory calls the renovation “a great gift” to Toronto because the cathedral’s history is so closely linked to the city’s history.

“We have done such a poor job in Toronto of retaining our heritage,” said Tory. “We have far too few places in Toronto where we’ve actually gone to the trouble of not just preserving the building but making sure it looks inside and out the way it looked originally.”

When one thinks of Toronto’s early days, the image that comes to mind is that of the English Protestant power brokers of the Family Compact pulling the levers of power in politics, business and religion. Catholics, and the Irish immigrants, were on the margins, many desperately poor or sick after sailing for weeks across the Atlantic.

Bishop Power and his successor, Bishop Armand de Charbonnel, were instruments of social change and spiritual growth, and the Irish and French influence on St. Michael’s Cathedral is strong and readily apparent. Just looking around in the renovated church one sees Irish and French symbols in abundance; from shamrocks to fleur-de-lis, stained glass windows and stations of the cross from Europe, and more.

If Bishop Power is the most important person in the creation and building of St. Michael’s — a symbol that proudly proclaimed in the mid-19th century that Catholics were here in Toronto to stay and help build the city — then Bishop de Charbonnel is a very close second.

Bishop Michael Power. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto (ARCAT).)

Bishop Michael Power. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto (ARCAT).)

“Charbonnel is a very underrated bishop,” said Fr. Seamus Hogan, Assistant Professor of Church History at St. Augustine’s Seminary and an expert on the bishops of the Archdiocese of Toronto. “The things he did are still being felt by people in the archdiocese today and affecting the lives of so many Catholics and others in the city.”

The stories of both these bishops — and their respective roles in the building of St. Michael’s — are fascinating history.

Bishop Power was born in Halifax in 1804, the eldest son of Irish immigrants. Incredibly, at just 11 years old, he was sent to Montreal to study for the priesthood in August 1816, according to Mark McGowan in his fascinating book Michael Power: The Struggle to Build the Catholic Church on the Canadian Frontier.

Growing up in Halifax, Bishop Power lived among English Protestants and learned religious tolerance and respect for other faiths. This would position him well years later in Toronto.

“He had a strong connection to England and he was very much an Empire Loyalist and that resonated well with the city fathers here,” said Fr. Busch. “They really loved the man. The fact that all the other faiths in the city came to dig out the foundation of the cathedral (in April 1845) attests to that.”

In 1827 at age 22, the bilingual future bishop was ordained in Quebec and went on to work as a missionary priest in outposts across Lower Canada for the next 14 years. In December 1841, a second diocese in Upper Canada was formed. Called the Diocese of Toronto, it was a huge area of land covering most of future Ontario, from west of Kingston to Windsor and north to what is now Thunder Bay. Bishop Power was appointed bishop and, being a modest man, he reluctantly accepted after doing his best to convince his superiors someone else might be better for the job.

Following papal approval, Bishop Power was consecrated on May 8, 1842 at age 37 and was formally installed upon his arrival in Toronto on June 26.

Once in Toronto, Bishop Power called a synod where he laid down a number of rules designed to rein in the free-wheeling frontier aspects of the huge new diocese. Known as “Power’s Rules,” priests were not allowed to wander outside of their assigned parishes; they were not allowed to charge a fee for the administration of the sacraments; churches were required to erect baptismal fonts and confessionals, as well as keep detailed baptism, marriage and funeral records. One rule irked many priests and that was the wearing of cassocks in public because they feared being targets of verbal and physical attacks from the Orange Order. Bishop Power believed that in order to put a permanent stake in the ground, Catholic priests had to be willing to proudly show they were Catholics, not only to their flock but to non-Catholics.

“He could be tough, but he was fair and he was hardworking and a real leader,” said Fr. Hogan.

Days after the synod, Bishop Power wrote to an Irish bishop who was educating and training priests. He laid out his challenges in this frontier diocese.

“I have but 20 clergymen throughout the whole county... I have neither colleges, nor schools, nor men… I pray to God most earnestly that the Irish College for Foreign Missions may prosper and fully answer all our expectations… I am determined to have a whole district without any spiritual assistance rather than to confide the poor people into the hands of improper or suspended men,” Power pleaded.

There were about 3,000 Catholics in Toronto and about 50,000 scattered across his diocese in 1842. After his installation, Power was out exploring and meeting people on pastoral visits to Penetanguishene, Manitoulin Island and down through what is now southwestern Ontario. It was likely during these travels that he settled upon the idea of erecting a permanent Catholic shrine at the heart of the diocese — St. Michael’s Cathedral.

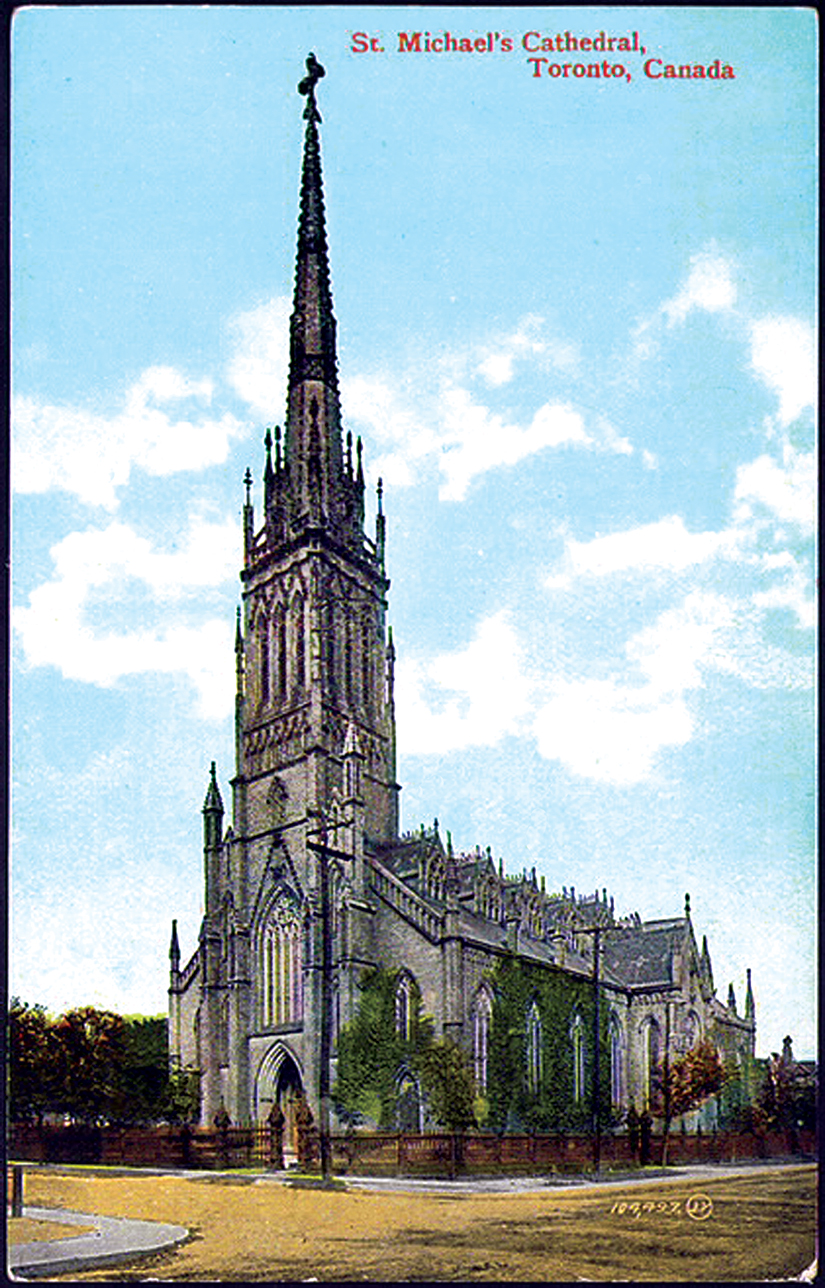

St. Michael’s Cathedral, circa 1910, as depicted on a postcard.

St. Michael’s Cathedral, circa 1910, as depicted on a postcard.

Construction began on the cathedral on April 7, 1845. Hundreds of men with ploughs, picks, axes, shovels, wagons and horses began digging the foundation. An oxen was barbecued and a grand party held to celebrate the beginning of the project.

John Harper was the contractor working to the plans of well-known cathedral architect William Thomas.

Over the course of its construction, many of the workers — from masons to carpenters and roofers to painters — were fresh off the boats from Ireland. Some worked for food, others for nominal wages. The crypt and the foundation were finished in under two months and, as per contract, for a grand total of £474.

The bishop’s palace, or rectory, was completed first and blessed on Dec. 7, 1846. In 1847, there were still only 25 priests in the Diocese of Toronto and Bishop Power knew he needed more. So he left on a six-month trip to Europe, seeking to recruit additional priests and to raise funds for the cathedral. In Ireland, he witnessed the devastation of the potato famine. Tens of thousands of Irish would migrate to Toronto and his diocese and be the direct human link between St. Michael’s and the potato famine.

When he returned to Canada in the summer of 1847, Bishop Power began ministering to the newly arrived immigrants. However, many of the Irish who arrived in Canada during the late 1840s and early ’50s were infected with typhus and confined to “fever sheds” erected by the Toronto Board of Health. In the summer of 1847 alone, 863 Irish immigrants died of typhus.

There were at least 12 sheds and Bishop Power visited these miserable places often, as did other priests.

While the city lived in dread, Bishop Power brushed away fears of the contagious disease and tended to the plague-stricken and starving Irish immigrants.

Meanwhile, months before when he was in Ireland in 1847, Bishop Power arranged for the Loretto Sisters to establish a mission in Toronto. The first five sisters arrived on Sept. 16, 1847, to find Bishop Power totally engaged in caring for the typhus patients. Days later, the bishop himself contracted the disease and died on Oct. 1. Some 3,000 Torontonians of all faiths attended his funeral at nearby St. Paul’s Church. His body was then taken to unfinished St. Michael’s where he was placed in the crypt, long before a roof or windows were on the cathedral. (He remains there, through the restoration, along with the remains of more than 60 others.)

Though he was bishop only five years, Bishop Power achieved so much, not least of which was the unfinished cathedral, In 1848 the bishop of Montreal consecrated St. Michael’s Cathedral on Sept. 29, the Feast of St. Michael the Archangel.

Toronto was without a bishop until the 1850 appointment of Armand de Charbonnel, who, like Bishop Power, was also a social crusader and visionary. Bishop de Charbonnel came from a wealthy land-owning French family. One of the first things he did was sell property he owned in France to help pay off much of the huge debt on the cathedral, said Fr. Hogan.

“He’s also responsible for making it look beautiful by putting in that big chancery window and things like the stations of the cross. He really beautified it because he had the means to do so.”

He also took 10 per cent of money collected by priests in their parishes to be used for the ongoing construction of the cathedral and ratcheted up fundraising with donations coming from as far away as the United States and Europe and some of Toronto’s leading Protestants, such as George Brown.

Beyond beautifying the cathedral and nearly finishing it (the tower and spire were done in 1867), Bishop de Charbonnel launched initiatives still impact Toronto:

• – In 1850, he established the St. Vincent de Paul Society to help the poor;

• – In 1851, he brought the St. Joseph Sisters here to help the poor and sick and move into education;

• – In 1852, he brought the Basilian Fathers to Toronto and they started St. Michael’s College School;

• – In 1854, he established the Toronto Savings Bank to help the poor manage what little money and investments they had;

• – In 1857, he started the House of Providence which today still cares for the elderly but back then also looked after orphans and others in need;

• – All through his tenure, he was a tireless advocate for a separate school system for the Catholic minority in today’s Ontario.

“Bishop de Charbonnel was a brilliant man and a social justice crusader who really cared about the poor and he deserves so much credit for improving the lives of so many, not just back then but still today through his legacy,” said Fr. Hogan.

On the first day of construction, workers celebrated by roasting an ox similar to this.

On the first day of construction, workers celebrated by roasting an ox similar to this.