The director of the B.C. Aboriginal Network on Disability Society perfectly summarized last week’s delay in extending doctor-delivered death to the mentally ill. “It’s not like a win or anything,” Neil Belanger told Register reporter Anna Farrow.

Indeed, it was not anything like a win, especially for those deeply concerned — or angrily horrified — that the Trudeau government refuses to just scrub its legislation letting medical personnel administer lethal injections to Canadians with mental health afflictions.

If it was like anything at all, it was like the miasma of confusion that has infected the medical aid in killing (MAiK, as it should be called, not MAiD) debate since the lethal legal fog brought about by the Supreme Court’s 2015 Carter decision. In that ruling, the country’s top judges not only held, but wrote down on paper, the preposterous claim that it is discriminatory under our Charter of Rights to deny people their wish to be killed by public health care because it puts them at risk of becoming too weak to kill themselves.

Imagine that you are someone walking across a bridge who sees a forlorn soul sitting on the railing staring into the watery abyss below. Would you, being you, step up and ask: “Hey there, want me to give you a push in case you can’t manage the jump later?” And, no, your name can’t be Ted Bundy or John Wayne Gacy.

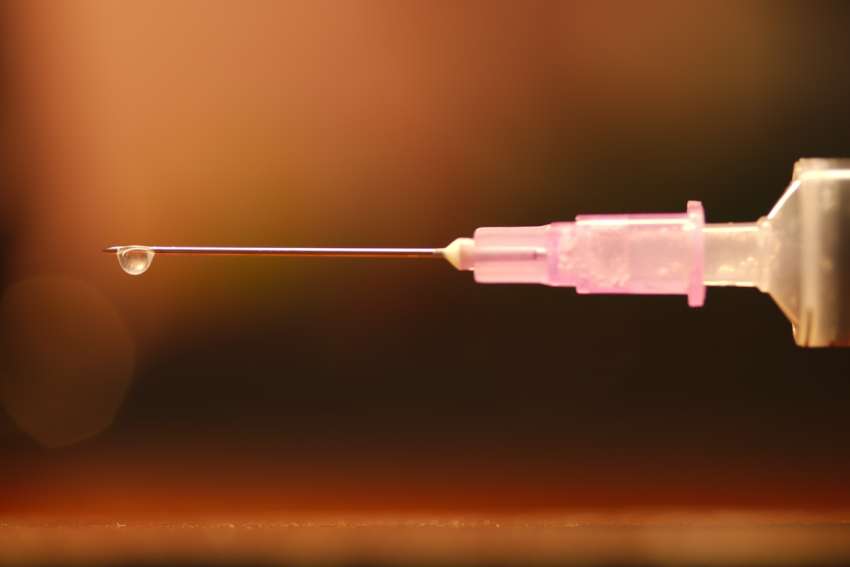

At least the SCOC had sufficient shreds of wisdom left at the time of Carter to add the proviso that death at least had to be foreseeable. Totally predictably, no sooner had the ink dried on Canada’s first MAiK/MAiD legislation in 2016 than medicalized death merchants began clamouring for expansion, leading us to the fastest growth in medically inflicted homicide in the world. And here we are, with the lives of mentally ill Canadians balanced on the needle point of a health-care practitioner’s syringe.

If confusion was a necessary consideration for all this in the beginning, it has now reached the border country of delirium. Consider the inherently contradictory arguments advanced for medically ending the lives of people afflicted with maladies from depression to bipolar disorder and beyond. The first salvo is routinely the claim that such conditions are — or at least can be — a form of torture. But under logical and language scrutiny, the claim is exposed as pure emotional political distraction. No one with a brain or heart would deny that mental illnesses reach the level of utter torment. But torture, in its meaning of extreme physical or mental agony, is what rogue States, terrorists or criminal gangs inflict on their victims. It connotes acts such as non-consensual fingernail removal, water boarding, and electrical shocks applied to tender bits of bodies. It is why as a matter of ironclad law we don’t accept confessions extracted by torture: there’s no way of knowing if victims meant what they said or said it only to make the agony stop.

Yet those seeking to extend medical aid in killing to those in mental-health crisis then double down on the confusion they’ve created. They contend it is discriminatory to deny that those suffering the “torture” of psychological breakdown are in a fit state of mind to choose doctored death. So… mental illness is torture but not torture that makes people say things they might not truly mean? So… torture that isn’t really torture? In other words, political hyperbole to achieve the pre-determined end of killing those whose suffering can’t otherwise justify death as a solution.

There lies the final confusion. How did Canada’s elites get us into this morass of medical death, which has left countries around the globe wondering whether we’ve lost our collective mind? As Neil Belanger correctly told The Register, the current delay in legislating medical death for the mentally ill is not a win. But let us pray it gives us time for clarity to finally stop the madness our political, medical, legal and media minds have inflicted on us.