In the ancient Mediterranean and Middle East, that was literally true. Covenants and treaties were sealed with a sacrifice and the sprinkling of the two parties with some of their blood. After all, blood was the bearer of life and imbued with power and awe. To seal the covenant in blood signified that it was serious business and that the one breaking the agreement could expect dire consequences.

In Exodus’ account of the covenant between God and the people of Israel, the same pattern was followed. The people all enthusiastically and unequivocally voiced their commitment and willingness to do what the Lord had commanded.

There were no dissenting voices or waffling reported in the story. This was most likely an idealized account, for tent-revival type commitments usually don’t have a long life.

The Old Testament bears witness to the catastrophic failures of the people of God throughout their history. They often brought disaster on their heads for human sin usually sets off a chain reaction of consequences. Christians have not fared any better in their collective commitment to live up to the terms of their covenant with God. Human weakness is always with us, and the best of intentions waver and crumble over time. But even though humans did not keep their commitment, God kept His. God always has and always will. The covenant was always renewed and people were given the chance to start anew — often after experiencing suffering and struggle. Our own culture has even more difficulty with commitment, integrity, keeping one’s word and truth-telling. Remaining faithful to any commitment or sense of duty and honour, especially one spiritual in nature, is a very eloquent counter-cultural witness. But we cannot allow the faults and failures of others or of institutions to deflect us from the path that leads to life.

According to the theology of the author of the Letter to the Hebrews, sacrifice was at an end. The use of animal blood during sacrifices had a very limited ability to cleanse and purify, but the blood of Christ — the Son of God and Sinless One — was definitive and final. Humanity can continue the journey with a clear conscience and an assurance of a heavenly inheritance. This new covenant was indeed written in blood, but it will never have to be rewritten.

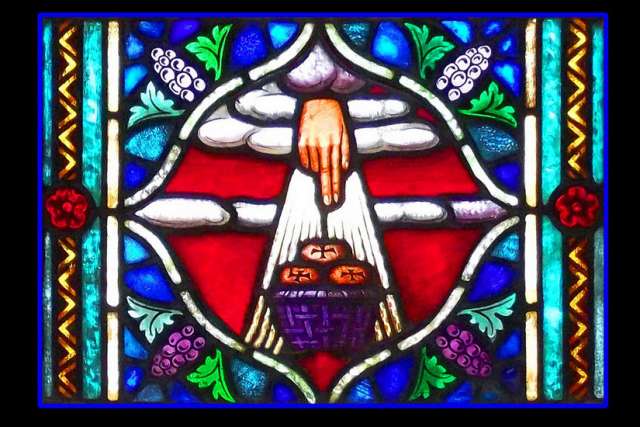

Mark’s description of the Last Supper is very simple but profound. It was a Passover meal, so it celebrated not only the liberation from slavery of the Jewish people many centuries before, but the redemption of humanity that the death of Jesus would inaugurate. The bread that Jesus blessed was His body that would be broken and divided, providing sustenance, nourishment and life for so many throughout the ages. Jesus saw His own death as the realization of the kingdom of God and the beginning of a new covenant between God and humanity. The phrase “for many” should be understood in the context of Semitic languages as a collective meaning “for all.” The blood of Jesus that was poured out was not some sort of price paid to assuage the wrath or wounded honour of God. His death was due to His utter fidelity to the mission God had given Him as the teacher and redeemer of humanity. He had not allowed personal safety or human concerns to hinder Him in any way. It was an act of self-giving love — His death would provide inspiration and the supreme example for people until the end of time.

The new covenant symbolized by His body and blood was not intended as merely a personal devotion or an assurance of heaven. To share the Eucharist with other believers was and should still be an act of public commitment, much like the one in the reading from Exodus. It was a promise and a commitment to be a disciple, not just a fellow traveller, and to continue the work of Jesus, labouring in His kingdom on behalf of others. And so it should be for us — how much does our celebration of the Eucharist affect the rest of our week?