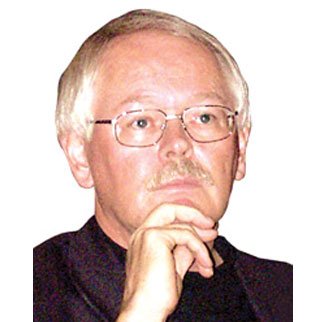

Fr. Ron Rolheiser

Ronald Rolheiser, a Roman Catholic priest and member of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, is president of the Oblate School of Theology in San Antonio, Texas.

He is a community-builder, lecturer and writer. His books are popular throughout the English-speaking world and his weekly column is carried by more than seventy newspapers worldwide.

Fr. Rolheiser can be reached at his website, www.ronrolheiser.com.

Consider the human heart’s complexity

In a book on preaching, entitled, Telling the Truth, Frederick Buechner challenges all preachers and spiritual writers to speak with “awful honesty” about the human struggle, even inside the context of faith. Don’t put an easy sugar-coating on things, he warns:

“Let the preacher tell the truth. Let him make audible the silence of the news of the world with the sound turned off so that in that silence we can hear the tragic truth of the Gospel which is that the world where God is absent is a dark and echoing emptiness; and the comic truth of the Gospel, which is that it is into the depth of this absence that God makes himself present in such unlikely ways and in such unlikely people that old Sarah and Abraham and maybe when the time comes even Pilate and Job ... and you and I laugh till the tears run down our cheeks. And finally let him preach this overwhelming of tragedy by comedy, of darkness by light, of the ordinary by the extraordinary, as the tale that is too good not to be true because to dismiss it as untrue is to dismiss along with it the catch of the breath, the beat and lifting of the heart near to or even accompanied by tears, which I believe is the deepest intuition of truth that we have.”

Reading this, I was reminded of some of the preaching in my own parish when I was a young boy. I grew up in a small, sheltered, farming, immigrant community in the heart of the Canadian prairies. Our parish priests, wonderfully sincere men, tended however to preach to us as if we were a group of idyllic families in the TV series Little House on the Prairies. They would share with us how pleased they were to be ministering to us, simple farm-folk, living uncomplicated lives, far from the problems of those who were living in the big cities.

The gift that was Henri Nouwen

Fr. Henri Nouwen was perhaps the most popular spiritual writer of the late 20th century and his popularity endures today. More than seven million of his books have been sold world-wide and they have been translated into 30 languages. Fifteen years after his death, all but one of his books remain in print.

Many things account for his popularity, beyond the depth and learning he brought to his writings. He was very instrumental in helping dispel the suspicion that had long existed in Protestant and Evangelical circles towards spirituality, which was identified in the popular mind as something more exclusively Roman Catholic and as something on the fringes of ordinary life. Both his teaching and his writing helped make spirituality something mainstream within Roman Catholicism, within Christianity in general, and within secular society itself. For example, American Secretary of State Hilary Clinton has stated that his book, The Return of the Prodigal Son, is the book that has had the largest impact on her life.

He wrote as a psychologist and a priest, but his writings also flowed from who he was as a man. And he was a complex man, torn always between the saint inside of him who had given his life to God and the man inside of him who, chronically obsessed with human love and its earthy yearnings, wanted to take his life back. He was fond of quoting Soren Kierkegaard who said that a saint is someone who can “will the one thing,” even as he admitted how much he struggled to do that. He did will to be a saint, but he willed other things as well: “I want to be a saint,” he once wrote, “but I also want to experience all the sensations that sinners experience.” He confessed in his writings how much restlessness this brought into his life and how sometimes he was incapable of being fully in control of his own life.

In the end, he was a saint, but always one in progress. He never fit the pious profile of a saint, even as he was always recognized as a man from God bringing us more than ordinary grace and insight. And the fact that he never hid his weaknesses from his readers helped account for his stunning popularity.

His readers identified with him because he shared so honestly his struggles. He related his weaknesses to his struggles in prayer and, in that, many readers found themselves looking into a mirror. Like many others, when I first read Nouwen, I had a sense of being introduced to myself.

And he worked at his craft, with diligence and deliberation. Nouwen would write and rewrite his books, sometimes five times over, in an effort to make them simpler. What he sought was a language of the heart. Originally trained as a psychologist, his early writings exhibit some of the language of the classroom. However, as he developed as a writer and a mentor of the soul, he began more and more to purge his writings of technical and academic terms and strove to become radically simple, without being simplistic; to carry deep sentiment, without being sentimental; to be self-revealing, without being exhibitionist; to be deeply personal, yet profoundly universal; and to be sensitive to human weakness, even as he strove to challenge to what’s more sublime.

Few writers, religious or secular, have influenced me as deeply as Nouwen. I know better than to try to imitate him, recognizing that what is imitative is never creative and what is creative is never imitative.

Where I do try to emulate him is in his simplicity, in his rewriting things over and over in order try to make them simpler, without being simplistic. Like him, I believe there’s a language of the heart (that each generation has to create anew) that bypasses the divide between academics and the street and which has the power to speak directly to everyone, regardless of background and training. Jesus managed it. Nouwen sought to speak and write with that kind of directness. He didn’t do it perfectly, nobody does, but he did do it more effectively than most. He recognized too that this is a craft that must be worked at, akin to learning language.

I dedicated my book The Holy Longing to him with this tribute: “He was our generation’s Kierkegaard. He helped us to pray while not knowing how to pray, to rest while feeling restless, to be at peace while tempted, to feel safe while still anxious, to be surrounded by light while still in darkness and to love while still in doubt.”

If you are occasionally tortured by your own complexity, even as your deepest desire is to “will the one thing,” perhaps you can find a mentor and a patron saint in Henri Nouwen. He calls us beyond ourselves, even as he respects how complex and difficult that journey is. He shows us how to move towards God, even as we are still torn by our own earthly attachments.

(Fr. Rolheiser can be reached at his web site www.ronrolheiser.com.)