Cardinal Thomas Collins believes the Archdiocese of Toronto’s founding bishop was a martyr and is a saint. On the occasion of the archdiocese’s 175th anniversary, Collins announced he plans to begin the process that could make it official.

A message from the Cardinal

My Dear Friends,

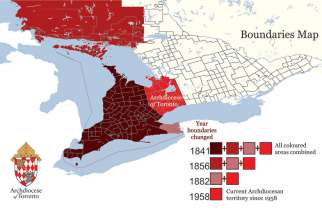

On December 17, 2016, the Archdiocese of Toronto celebrated its 175th anniversary, launching a year-long celebration to commemorate this historic milestone. Established in 1841 with 22 parishes and Michael Power as its first bishop, the archdiocese has grown to become a vibrant and diverse faith community of more than two million people. Together we celebrate the sacraments each week in more than 30 languages at our 225 parishes. We are truly blessed.

The Catholic Register has created this special commemorative magazine to reflect on our past, recalling the humble beginnings of our faith journey and to celebrate our many blessings along the way. We are forever indebted to those who came before us, sacrificing much and giving in abundance to plant the seeds of faith, outreach and service for generations to come.

Let us continue to follow their example of generosity and fidelity, ever mindful that our own witness can serve as a beacon of hope, love and inspiration. To all those who serve so faithfully: our priests, religious men and women and Catholics across the archdiocese, be assured of my gratitude for all that you do to spread the Good News.

As we celebrate our 175th anniversary, we ask for God’s blessing in our daily journey of faith. May we continue to build on the foundation established by Bishop Power and all those who have followed.

Yours sincerely in Christ,

![]()

Thomas Collins

Archbishop of Toronto

Anniversary Prayer

A special prayer for the 175th anniversary of the Archdiocese of Toronto

Loving Father,

We turn to you with gratitude for the many blessings you have generously bestowed

upon the people of the Archdiocese of Toronto,

who from the very beginning have arrived here from many nations to find

and strengthen a community of faith,

where we have been able to encounter your Son in our joys and sorrows.

As the Archdiocese celebrates its 175th anniversary,

we ask you to continue to bless your people with the gifts of the Holy Spirit,

so that all clergy, religious and faithful may be gathered and strengthened in their mission of

constantly proclaiming the wonderful works of salvation to all we meet.

We ask this through Christ our Lord. Amen.

Just off the boundaries of Mary Ward Catholic Secondary School there’s the site of a 600-year-old Huron-Wendat village — longhouses, sweat lodges and plots where people grew squash and beans. That little shard of Toronto’s mostly forgotten, 10,000-year history of human habitation reflects a little of the good news and bad news Toronto has accumulated in its Catholic history.

A history defined by Catholic charity

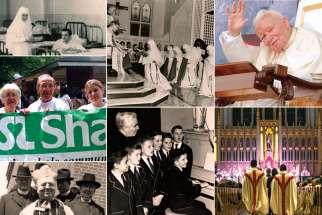

Catholic charity and the spirit of giving, regardless of a recipients’ religious affiliation, have been instrumental in shaping Toronto’s social, health care and political history through three centuries.

The Greater Toronto Area would be a vastly different place today without the fundamental commitment to charity that was mobilized in the archdiocese’s earliest days.

“We tend not to be boastful, but you have to get up and tell this story sometimes,” says Michael Fullan, executive director of Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Toronto. “It’s that important. And it’s not the work of my office, it’s the work of our member agencies.”

Catholic Charities, an umbrella group for 26 individual charitable organizations, was the brainchild of Archbishop Neil McNeil in 1913. But Catholic giving has been making its mark around Toronto for as long as the archdiocese has existed, perhaps longer. And so many different people have contributed, from bishops, priests and nuns to lay people, volunteers and administrators.

An interesting example of Catholic charity impacting both society and politics sits in the west end overlooking Lake Ontario and seen by thousands of commuters every week. Today it’s known as St. Joseph’s Health Centre, but it started as an orphanage and evolved into a first-class hospital due to the quick wits and vision of the Sisters of St. Joseph, who arrived in Toronto in 1851.

The Sacred Heart Children’s Orphanage — known as Sunnyside Orphanage — began around the time of Confederation to ease the overcrowding at the House of Providence on Power Street, which opened in 1857. (It moved to Scarborough in 1962 as Providence Villa and today is known as Providence Healthcare.)

At the House of Providence in the 1870s, about 300 orphans and several hundred poor and elderly adults, many so-called “incurables,” were being looked after by the Sisters of St. Joseph, nicknamed the “Sisters of Charity.” Despite best efforts, conditions would have been desperate, especially for children living amongst the dying.

“There was a large oven where the sisters baked bread for the children,” says Fr. Seamus Hogan, Assistant Professor of Church History at St. Augustine’s Seminary and an expert on the early bishops of the Archdiocese of Toronto. “The locals would say the oven was never cool to the touch.”

To ease the overcrowding, the Sunnyside Orphanage was opened in a large four-storey rented house owned by prominent 19th-century Toronto architect and developer John George Howard. In 1881, the nuns and the archdiocese bought the property, expanded it to both boys and girls a decade later, and served the needs of at-risk kids and orphans for three decades. But then, in the early 20th century, the city’s rapid expansion put the orphanage at risk. The sisters used political guile to outfox the politicians.

“In typical fashion,” notes the Toronto Historical Association website, “the City of Toronto decided to expropriate the property for use as a school in the growing residential area. To prevent the expropriation, the Sisters of St. Joseph and the diocese decided to convert the property into a hospital, which could not be expropriated.”

A couple of Felician sisters makes a social service call to a Toronto family. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

A couple of Felician sisters makes a social service call to a Toronto family. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

The orphanage was moved and in 1921 an important health care facility came to the west end. This was not the first political tussle for the Sisters of Charity. In 1892 they founded St. Michael’s Hospital. The next year, the city’s fathers wanted to withdraw grants to the hospital, in part by questioning the medical qualifications of the sisters. For help, they called upon Archbishop John Walsh, a likeable and dignified man who was not one “to inflame sectarian feeling or to embitter the relations between Catholic and Protestant,” as the Globe reported.

“If the occasion arose, however, Walsh was certainly capable of venting his anger,” writes Michael Power (not Toronto’s first bishop) in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. “In June 1893, when municipal politicians withdrew grants from all sectarian hospitals (including St. Michael’s), the archbishop dispensed with diplomacy and immediately responded with a scathing denunciation. In a brilliantly argued circular letter published in The Catholic Register, he vigorously defended the right of all hospitals to a share of public money. Within a week, the city council had reversed its decision and restored the grants.”

In his letter, Walsh called the city council’s actions “blind and brutal bigotry…. We must enable it to keep its doors wide open for the sick and poor, whether Catholic or Protestant. No child of misfortune of any creed or colour must ever be refused its sacred hospitality when suffering from the pangs of disease.”

Today, St. Michael’s is celebrating its 125th anniversary and remains a vital health care provider in the heart of Toronto.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, there was much Catholic charity in the diocese; beginning with the first bishop, Michael Power, whose ministering to the ill in the typhus “fever sheds” cost him his life. The second bishop, the unheralded and underrated Armand de Charbonnel, launched many charitable initiatives: founding the Toronto Savings Bank to help the poor save their money, bringing the St. Vincent de Paul to Toronto and spearheading Providence. The latter two still exist today, helping thousands every year.

“Charbonnel, although from a rich family, would join lay people visiting the poor in their homes. This was a powerful message of trying to be in solidarity with the poor,” Hogan said.

Succeeding Charbonnel was Bishop John Lynch, whose episcopal motto was, “He has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor.” He worked with the Sisters of St. Joseph in expanding Providence House, creating the St. Nicholas Home for Working Boys, founding the Sunnyside Orphanage for boys and establishing the Notre Dame Institute, a boarding-home for working girls and female students.

Following Bishop Lynch was Bishop Walsh, who, beyond saving public money for hospitals, founded the St. Vincent de Paul Children’s Aid Society of Toronto in 1894, the forerunner of Catholic Children’s Aid Society.

By the time Neil McNeil was named archbishop in 1912, those in need were being served by many well-established Catholic organizations. But Archbishop McNeil understood the delivery of services could be uneven, and there was no central body to oversee individual charities while keeping the chancery office informed and making long-range plans to meet future needs.

St. Michael’s Hospital, circa 1914, was established by the Sisters of St. Joseph in 1892. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

St. Michael’s Hospital, circa 1914, was established by the Sisters of St. Joseph in 1892. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

It was visionary thinking. Over the years, as the face of the archdiocese has changed, Catholic Charities has changed with it, ensuring that services meet existing needs while anticipating future ones.

What has remained unchanged, however, is the mandate at the heart of Catholic Charities: “Not only do we allocate the funds that ShareLife raises, but we also hold our agencies accountable for the provision of services within the Catholic tradition,” Fullan says.

At its core is Catholic social teaching focused on the poor and marginalized, urging citizens to build a just society and safeguard the dignity of every person. Bishops Power, Charbonnel, Lynch, Walsh and McNeil laid the groundwork that continues decades later.

For example, to ensure gaps were getting plugged and services were of the highest quality, in 1913 Archbishop McNeil appointed Fr. Patrick Bench superintendent of the newly created Catholic Charities. Regular reviews of each agency for “good practice and good Catholic practice” continues to this day, Fullan says.

There have been many challenges, of course, and, as is often said, history repeats itself. For instance, until 1919 individual charities were on their own in terms of fundraising. Then Catholic Charities shifted its operations with the formation of the Federation of Community Service to pool fundraising efforts. It was the forerunner of the United Way and various religions worked together to raise money for the greater good. It was very effective, resulting in a dramatic increase in funding for member agencies.

Then, to ensure the right services were getting to the people who needed them most, Archbishop McNeil commissioned an archdiocese-wide needs assessment. The results led to the creation of the Catholic Welfare Bureau, which was responsible for providing services for Catholic Charities, including family and child care services. Unfortunately, the fundraising benefit of the Federation of Community Service would last less than a decade. In 1927, the federation announced Catholic agencies and institutions would not be eligible to receive any funds in the coming campaign.

Was it the same anti-Catholic bigotry that threatened St. Michael’s Hospital almost 35 years earlier? Explanations for the decision vary. But the fact is Catholics, by and large, were poorer, made up of more immigrants and in need of social services more than others. That means they requested more of the money raised.

Archbishop McNeil, stunned by the decision, acted quickly and turned to the Catholic community for help. Along with religious and lay leaders, the archbishop launched the Federation of Catholic Charities, a reorganized version of Catholic Charities that included a fundraising component. In three weeks, almost $200,000 was raised.

(This “going alone” strategy would be a valuable precedent nearly 50 years later for Archbishop Philip Pocock when he established ShareLife. More on that later.)

The Great Depression of the 1930s stretched Catholic Charities to the limit, prompting salary cuts, services being triaged and budget tightening. But again, Catholics stepped up and staff at member agencies and a fleet of volunteers rose to the challenge of tough times, while those in the pews gave what they could to make it through those lean years.

St. Michael’s Hospital today is a major teaching and research medical facility. (Photo courtesy St. Michael’s Hospital)

St. Michael’s Hospital today is a major teaching and research medical facility. (Photo courtesy St. Michael’s Hospital)

With the end of the Depression came World War II and a united front against a common enemy. The city even saw a return to a unified charitable effort with the creation of the United Community Fund, the precursor to today’s United Way. It was such a success that Catholic Charities was able to raise salaries, expand services and improve agency facilities.

After the war, the federation, now operating under the name the Council of Catholic Charities, found a new director in Fr. John Fullerton (later Msgr. Fullerton). Known for his people skills, he had the diplomacy and intelligence needed to negotiate budgetary issues with the United Community Fund, as well as handle increasing negotiations with the provincial government.

In a clear indication of Catholic Charities’ increasing public profile, Fr. Fullerton was asked to serve as vice-chair of the three-person Ontario Hospital Services Commission.

In this role, his recommendations contributed to legislation that led to the eventual creation of OHIP, Ontario’s public health insurance plan.

For Catholic Charities, life was good for many post-war years with an expansion of amenities such as the establishment of Sancta Maria House, a home for girls with special needs, and many other needed social services for the poor and marginalized. But a crisis of thunderbolt proportions appeared in 1976. The United Way voted to admit the Planned Parenthood Association of Toronto, a group offering abortion counselling.

Planned Parenthood’s admission represented only a sliver of United Way funding, but its mere presence was an insurmountable obstacle for Catholics. After negotiations between United Way and Archbishop Pocock proved fruitless, the Council of Catholic Charities withdrew from United Way. To replace the lost funding, ShareLife was launched. No doubt, Neil McNeil’s need to go alone in 1927 gave Archbishop Pocock further confidence for ShareLife’s future success.

Today, the Archdiocese of Toronto is Canada’s largest diocese, stretching north to Georgian Bay and from Oshawa to Mississauga with almost two million Catholics. Catholic Charities this year will allocate $9.1 million to its member agencies to serve more than 200,000 people from downtown Toronto to Durham Region to Simcoe County to Dufferin-Peel.

For Catholic Charities, things are much different than in Neil McNeil’s time, but the philosophy of working together to best serve the poor and needy remains the same.

“I’ve been saying we need to do more together differently,” Fullan says, adding that shared services such as financial management and HR support have been a boon to its member agencies.

Later this year, once a pilot project is completed, shared IT support should be rolled out to all 26 agencies, Fullan says, enabling smaller agencies to take advantage of services they might not otherwise be able to afford, and ensuring that money given to ShareLife can be stretched as far as possible.

It also proves, once again, that even as times and needs change, the spirit of Catholic charity remains the same throughout the archdiocese.

St. Augustine’s Seminary ensured a healthy Church

For almost half a century after Confederation, young men training to be priests in the Archdiocese of Toronto were sent to Montreal for formation because there was no seminary in English Canada

The Archdiocese of Toronto’s vast geography and ever-increasing population have presented challenges for all of its bishops since the diocese was born 175 years ago. So much so that a recurring story of the archdiocese has been its growth followed by subdivision.

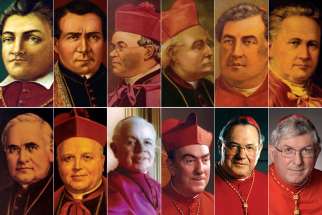

Bishop Michael Power

Bishop Michael Power

A native of Halifax, Michael Power was founding bishop of the Diocese of Toronto and the first English-speaking bishop born in Canada.

He arrived in Toronto in 1842 and quickly went to work building Canada’s newest diocese, which at the time encompassed the Niagara Peninsula, all of southwest Ontario to Windsor and north to Lakes Huron and Superior.

Among his achievements was founding St. Michael’s Cathedral. Construction began in April 1845; however, Bishop Power did not live to see it completed. While ministering to immigrants dying of typhus, he contracted the disease and died in 1847 shortly before his 43rd birthday. He was buried beneath his unfinished cathedral.

Bishop Armand François Marie de Charbonnel P.S.S.

Bishop Armand François Marie de Charbonnel P.S.S.

Toronto was without a bishop for 30 months until Armand François Marie de Charbonnel was consecrated in the Sistine Chapel by Pope Pius IX on May 26, 1850 and sent to succeed Michael Power.

Over the next decade, he doubled the number of priests and parishes. He built 23 new churches as the Catholic population grew to 43,000. He used personal funds to finish the Cathedral and brought the Basilian Fathers, the Christian Brothers and the Sisters of St. Joseph to Toronto to staff schools and provide services for the poor.

He retired in 1860 and adopted a monastic life in his native France. He died in 1891 at age 88.

Archbishop John Joseph Lynch C.M.

Archbishop John Joseph Lynch C.M.

Irish-born, John Lynch became Toronto’s coadjutor bishop in 1859 and succeeded Bishop de Charbonnel one year later. He became Toronto’s first archbishop in 1870 when Toronto was raised to an archbishopric by Pope Pius IX.

Under Archbishop Lynch, 70 priests were ordained as he built 40 churches and seven convents, while supporting the Sisters of St. Joseph who expanded services for the poor and opened Sunnyside Orphanage. He also welcomed the Redemptorist Fathers, Carmelite Sisters, Sisters of the Precious Blood and Sisters of the Good Shepherd to Toronto.

He fell ill in 1882 and was assisted by Auxiliary Bishop Timothy O’Mahoney until his death in 1888 at age 72.

Archbishop John Walsh

Archbishop John Walsh

John Walsh was made archbishop in a ceremony marred by some Orangeman pelting his carriage with stones as he arrived at St. Michael’s Cathedral. Irish born, he came to Toronto from Sandwich (now Windsor, Ont.), where he had served as bishop since 1867.

He continued the work of his predecessors in solidifying Catholic health, education and social services. He also undertook a Cathedral restoration by adding St. John’s Chapel and redecorating the Cathedral’s interior. As St. Michael’s Cemetery neared capacity, he opened Mount Hope Cemetery in 1898. He also founded the St. Vincent de Paul Society.

Archbishop Walsh died in 1898 at age 68 and was buried in St. Michael’s Cathedral.

Archbishop Denis O'Connor C.S.B.

Archbishop Denis O'Connor C.S.B.

Denis O’Connor was born in Pickering, schooled at St. Michael’s College, ordained by Bishop John Lynch in 1863 and became Bishop of London in 1890.

Made Archbishop of Toronto in 1899, he was a disciplinarian who enforced a doctrinal rigour that upset some priests and laity. He stressed religious instruction in schools. A proponent of fiscal restraint, he opened just four new parishes despite a sharp rise in the Catholic population. He did, however, commission a shrine to honour the Jesuit martyrs in Huronia, which eventually became the Martyrs’ Shrine.

Ill health and the burdens of office caused him to resign in 1908. He died in 1911.

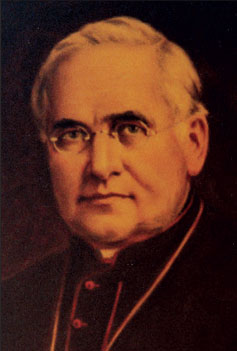

Archbishop Fergus McEvay

Archbishop Fergus McEvay

Fergus McEvay accomplished much in just three years as Toronto archbishop. Born in Lindsay and educated at St. Michael’s College, he was made Bishop of London in 1899 and replaced Denis O’Connor as Toronto archbishop in 1908.

He quickly established seven new parishes and approved construction of 10 churches. He also founded the Canadian Catholic Extension Society (which became Catholic Missions In Canada) and assured generations of Canadian ordinations by launching construction of St. Augustine’s Seminary.

Suffering from a blood disease since his arrival in Toronto, Archbishop McEvay, age 58, died on May 10, 1911 — before the seminary opened — and was interred at St. Augustine’s.

Archbishop Neil McNeil

Archbishop Neil McNeil

A Nova Scotia native, Neil McNeil served two years as Archbishop of Vancouver before 22 years as Archbishop of Toronto, starting in 1912. They were years in which Toronto’s Catholic population doubled.

In addition to completing St. Augustine’s Seminary, Archbishop McNeil created 32 new parishes, including parishes for non-English speaking immigrants.

He also campaigned for fair distribution of taxes to Catholic schools, and encouraged good relations between Catholics and Protestants, leading to the creation of the Federation of Catholic Charities. He oversaw the launch of the China Mission Seminary (later the Scarborough Foreign Missionary Society) and the Newman Club. He died on May 25, 1934, buried at St. Augustine’s Seminary.

Archbishop James Cardinal McGuigan

Archbishop James Cardinal McGuigan

James McGuigan was made Archbishop of Regina at age 35 and remained five years before being named Archbishop of Toronto in 1934. The PEI native led the archdiocese for an unprecedented 36 years. In 1946, he became Canada’s first-English speaking cardinal, and participated in the 1958 conclave that elected Pope John XXIII.

He initiated successful fundraising campaigns to pay the debt on St. Augustine’s Seminary, raise money for Catholic Charities, open high schools and add new parishes with ethnic priests to serve the immigrants who poured into Toronto following World War II.

Assisted for health reason after 1961 by coadjutor Archbishop Philip Pocock, he resigned in 1971 and died in 1974.

Archbishop Philip Porock

Archbishop Philip Porock

Philip Pocock became a bishop at age 37 and went from Bishop of Saskatoon to Archbishop of Winnipeg to coadjutor and then Archbishop of Toronto in 1971.

Born in St. Thomas, Ont., he arrived as Vatican II was being implemented and managed the transition by creating a senate of priests, a pastoral council and by urging laity to become more active in parish life.

During his seven years, several new parishes were opened. But he is best remembered for launching ShareLife after removing Catholic Charities from the United Way.

Health issues caused him to resign as archbishop in 1978 but he remained an active priest until his death at age 78 in 1984.

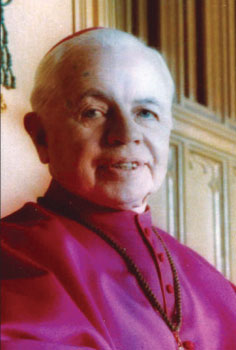

Archbishop Gerald Emmett Cardinal Carter

Archbishop Gerald Emmett Cardinal Carter

A Montreal native, Gerald Emmett Carter made his mark in Catholic education in his home city before being named Auxiliary Bishop of the Diocese of London and then Bishop in 1964. He was appointed Archbishop of Toronto in 1978. One year later, he was elevated to the College of Cardinals.

The cardinal was active in improving race relations, fighting against abortion, protecting the rights of Catholics and securing affordable housing for low-income families, senior citizens and the disabled. He was also active in opening Covenant House for street youth and in gaining full government funding for Catholic high schools.

He resigned as archbishop in 1990 and died in 2003 at age 91.

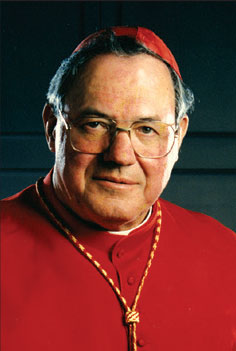

Archbishop Aloysius Cardinal Ambrozic

Archbishop Aloysius Cardinal Ambrozic

A native of Slovenia, Aloysius Ambrozic was appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Toronto in 1976. He became coadjutor Archbishop to Cardinal Carter in 1986, became Archbishop in 1990 and was elevated to the College of Cardinals in 1998.

As archbishop for 16 years, he saw Canada’s largest diocese become a multicultural, multi-racial community that grew from 1.1 to 1.6 million Catholics. He built 25 new churches, most in the rapidly expanding suburbs around the city, as ethnic parishes and groups flourished. He also created an office of youth ministry to develop spiritual and social programs for young people.

He retired as archbishop in 2006 and died in 2011 at age 81.

Archbishop Thomas Cardinal Collins

Archbishop Thomas Cardinal Collins

After nine years in Alberta as Bishop of St. Paul and then Archbishop of Edmonton, Guelph native Thomas Collins returned to Ontario to be installed in 2007 as Archbishop of Toronto. He was made a cardinal in 2012.

He has led efforts to welcome refugees and highlight the persecution of Christians worldwide. He has also denounced assisted suicide and euthanasia while arguing for conscience-protection rights for health care professionals.

In 2012, he issued a Pastoral Plan for the archdiocese. He also led a successful Family of Faith capital campaign, which has exceeded $170 million in donations and pledges to support the goals of the pastoral plan. In 2016 he rededicated St. Michael’s Cathedral Basilica after an extensive restoration.

Finding faith on the frontier

Baptisms. Weddings. Funerals. Masses. Confessions. These routine aspects of Catholic life today were rare and often inaccessible just five generations ago.

An essential obligation in the life of any diocese is to ensure the reverent care of its dead. For the Archdiocese of Toronto, the Irish potato famine and a local typhus epidemic forced it to accelerate its thinking on this important duty in the earliest days of its history.

The Archdiocese of Toronto has come a long way in 175 years but the journey is far from over. Future years will see more parishes, more ministries and a vibrant Cathedral Square, connected not only in spirit but interconnected by technologies that will link St. Michael’s Cathedral Basilica with parishioners stretching from Oshawa to Midland to Oakville.

Speaking in many tongues is hallmark of parish life

On a Sunday morning a steady stream of parishioners files through the glass doors of possibly the most bustling church in the Archdiocese of Toronto. Latecomers with toddlers in tow scan the crowded pews for a seat. As the procession ends, the priest reaches the presider’s chair and raises his right hand to his forehead.

The story of faith: a timeline

FORMATIVE YEARS

FORMATIVE YEARS

- - 1841 Dec. 17: The Diocese of Toronto is created. Michael Power is appointed its first bishop.

- - 1848 Sept. 29: St. Michael’s Cathedral is consecrated. Catholic population reaches 50,000.

- - 1850 Sept. 22: Bishop Armand-François-Marie de Charbonnel is installed as second bishop of Toronto. He uses his personal estate to pay off debt on St. Michael’s Cathedral.

- - 1856: Diocese of Toronto is divided by the creation of the dioceses of Hamilton and London.

- - 1857: House of Providence opens. St. Paul’s Church Cemetery is closed after filling up quickly with the burials of Irish immigrants who had succumbed to typhoid fever.

- - 1859 April 29: Bishop de Charbonnel resigns, Bishop John Lynch becomes third Bishop.

- - 1870 March 18: Pope Pius IX raises Toronto to an Archdiocese.

- - 1876: Sacred Heart Orphanage is established on the site of today’s St. Joseph’s Health Centre.

- - 1892: St. Michael’s Hospital is founded by the Sisters of St. Joseph.

- - 1893: The Catholic Register newspaper is launched.

- - 1908 April 13: Archbishop Fergus Patrick McEvay is appointed Archbishop of Toronto.

- - 1908: Canadian Catholic Church Extension Society is founded (changed to Catholic Missions In Canada in 1999).

- - 1911: Catholic population is 70,000 and total number of churches is 92.

- - 1912 Dec. 22: Archbishop Neil McNeil appointed to head Toronto archdiocese.

- - 1913: Catholic Charities office is formed. … Aug. 28: Opening of St. Augustine’s Seminary.

- - 1924: China Mission Seminary is established next to St. Augustine’s Seminary, later becoming the Scarborough Foreign Mission Society.

- - 1935 March 20: Archbishop James C. McGuigan is installed in Toronto.

MODERN ERA

- - 1949: Catholic population is 197,000, served by 158 parishes and missions.

- - Establishment of the Diocese of St. Catharines.

- - 1970 April: Toronto School of Theology is incorporated.

- - 1971: Cardinal McGuigan resigns and is succeeded by Archbishop Philip F. Pocock.

- - 1974: May-June: The first 26 Permanent Deacons of the Archdiocese of Toronto are ordained.

- - 1976: ShareLife is established when Archbishop Pocock withdraws the Council of Catholic Charities from the United Way.

- - 1978 April 29: Archbishop Pocock resigns and Bishop Gerald Emmett Carter is installed.

- - 1979 May 26: Archbishop Carter is elevated to the Sacred College of Cardinals.

- - 1982: Covenant House is established in downtown Toronto.

- - 1984: Catholic population is 1,214,000, served by 214 parishes, missions and chapels.

- - 1985: Ontario Government passes legislation providing full funding to Catholic high schools.

- - 1990 March 17: Cardinal Carter resigns, succeeded by Archbishop Aloysius Ambrozic.

- -1992: Catholic population is 1,337,000, served by 233 parishes, missions and chapels.

- - 1998 Feb. 21: Archbishop Ambrozic is elevated to the Sacred College of Cardinals.

- - 2000 Nov. 5: Official blessing of St. Paul’s Church as a minor basilica.

- - 2002 July 23-28: World Youth Day in Toronto, presided over by Pope John Paul II.

- - 2002 Nov. 16: Canadian Catholic Bioethics Institute is opened.

- - 2006 Dec. 16: Cardinal Ambrozic resigns and Archbishop Thomas Collins appointed as the 10th Archbishop of Toronto.

- - 2012 Feb. 18: Archbishop Collins is elevated to the Sacred College of Cardinals.

- - 2016 Sept. 30: St. Michael’s Cathedral officially reopens and is consecrated as a minor basilica after a five-year, $28-million renovation.

- - Today: The Archdiocese of Toronto is Canada’s largest diocese. The Catholic population of 2 million is served by 225 parishes and includes 806 priests and 91 religious orders.

As long as there has been a Cobourg, St. Michael’s has looked after its Catholic population

For as long as Cobourg, Ont., has existed, St. Michael’s parish has been there for its citizens.

St. Michael’s parishioners were to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the town’s original Roman Catholic parish with an anniversary celebration on Oct. 27.

“We just want to celebrate the wonderful gift of a parish, a Catholic parish, that’s 175 years (old),” said Fr. Andrew Ayala, St. Michael’s pastor.

Ayala was to kick off the day of celebration with a 5 p.m. Mass, with a sold-out dinner to follow at Cobourg’s historical Victoria Hall.

The parish hasn’t always gone by the name St. Michael’s. When it was established in 1837 by Fr. A. Kernan, the parish took the name of St. Polycarp. The original church building opened on William Street, about three km from the current location at 379 Division St., two years later. When the doors opened, the small wooden church served a congregation of 50 souls.

By 1859 the capacity of the 1,029-square-metre church was deemed inadequate by the parish’s third pastor, Fr. Michael Timin, who served for 33 years at St. Michael’s. So construction began on a brick addition to double the building’s size.

Four years later a fire destroyed the original wooden structure. Restored in brick to match the addition, Bishop Patrick Phelan rededicated the parish to St. Michael, who remains the namesake to this day.

On June 9, 1895 the cornerstone of the current church was laid. The new building was finished in less than one year.

The spirit that helped establish the parish and keep it going for 175 years can be seen in today’s parishioners, said Ayala, and in the planning for the milestone celebration in particular. Planning for the anniversary celebration began in August. This is where parishioners really stepped up to the plate to make the celebration come to fruition.

“God is giving this parish a great gift in the people it has,” said Ayala. “If I have to say something about this parish it’s that the lay people take very seriously their mission in the parish.”

The entire event, organized in less than two months, is a testament to the large impact a small community can have when they come together, said Ayala.

“At the end of August I shared this idea first with my secretary and my secretary told me about one person in the parish, the former mayor of the town, who would be able to organize that,” said Ayala.

That person was Peter Delanty who Ayala asked to establish an organization committee. Before the pastor knew it Delanty gathered seven others to work on the celebrations.

“In math one plus one is two but in my mission we say one plus one equals 2,000 because we can do much more when we come together,” said Ayala.

This was a great help to Ayala. A native of Argentina, English is his second language. And as pastor of a parish that sees about 900 visitors between the three Sunday services alone, Ayala’s time is limited. When the four high schools, hospital, youth correctional centre, five retirement homes and countless house calls, which absorb much of his non-preaching time, were factored in Ayala needed the help.

By early September the committee began holding meetings and relaying their plans to Ayala for approval.

“A wonderful committee of parishioners were able to organize it so well, I’m very happy with that,” he said. “There’s so much spiritual work to do I would have never been able to organize it if it wasn’t for the lay people,”

Along with dinner, those in attendance will also be entertained by the local jazz band from St. Mary’s Catholic Secondary School, receive a history lesson from Delanty and hear from Peterborough’s Bishop Nicola De Angelis.