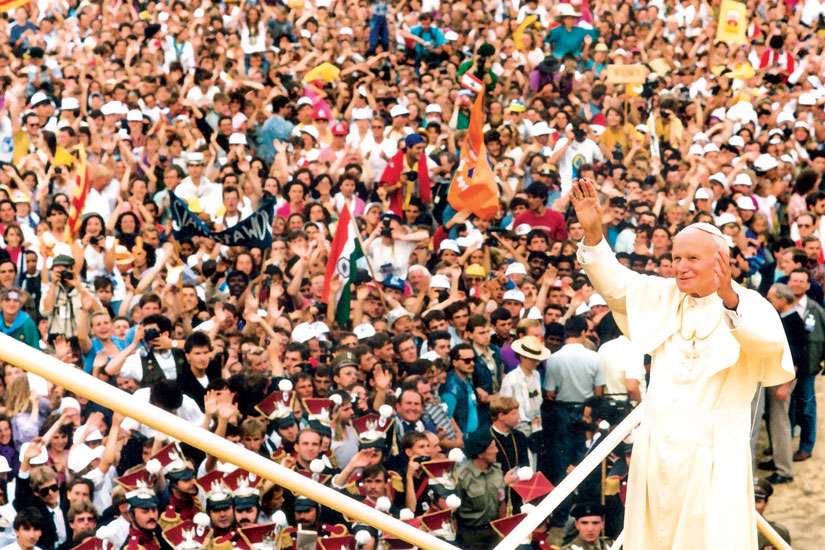

It was a week or two before Pope John Paul II was to land in Canada for World Youth Day in 2002. The photographers at this meeting had been chosen to contribute to a commemorative book about the event. With 20 different photographers looking at the Pope and the pilgrims from every possible angle, chances were these skilled professionals would (in fact, they did) produce a beautiful record of an unrepeatable episode in Canadian and Catholic history.

But many of them were commercial photographers who honed their craft photographing weddings, fashion spreads and shiny new products for sale. They weren’t photojournalists. One of these finally asked, “What if the Pope falls? What if he’s dying? Do we photograph that?”

The Pope obviously had Parkin- son’s (though the Vatican used to deny it). His curvature of the spine was increasingly painful to see. But he wasn’t retreating from the cameras or the crowds. He knew he would die and he wanted us to see it. This pope knew that to be human is to be mortal. He wanted us to see how life is lived right to the end. He was preaching with his body every time he walked out onto the St. Peter’s Square balcony, every time he mounted the popemobile, every time he struggled through his slurred and halting speech to say what he had to say.

The Pope was giving himself to us and to God, even in death. By photographing him we were inviting the world into something this old actor needed to show the world.

Just before John Paul II was to return to Rome, we were gathered in a hangar at Pearson International and one of the photographers turned to another and said, “Doesn’t the camera just love him? I can’t take a bad picture of the guy. I’m just saying, there’s something about him.”

Something indeed.

St. Pope John Paul II died in Vatican City, April 2, 2005 — ten years ago this week.

Mississauga Ontario’s St. Maximillian Kolbe, one of the biggest Polish parishes in the world with over 40,000 registered members and an average of 8,000 parishioners attending Sunday Masses, will mark the 10th anniversary with a special appearance by Warsaw auxiliary Bishop Rafal Markowski. He will celebrate the April 12, 11:00 a.m. Mass. The parish maintains its special relationship with St. Pope John Paul II with two first-class relics in the sanctuary — a spot of the Pope’s blood on a handkerchief and a cutting of his hair.

“People love him,” said St. Maximillian Kolbe pastor Fr. Janusz Blazejak. “They pray and venerate and ask graces from him.”

Blazejak’s parishioners remain profoundly moved by the Polish pope’s last lessons in dying.

“That image remains with the Polish people,” he said. “For Polish people it was the biggest retreat on dying and on suffering. That was something which they remember, because of his example of how to really suffer with dignity, to go to the next step, to die — he was an example for the elderly, shut-ins, sick people, people with terminal illness.”

As the Pope struggled to speak in the last week of his life, it was a message delivered in a universal language to the universal Church.

“He was so visible. He was there in public,” recalled theologian and executive director of the Canadian Catholic Bioethics Institute Moira McQueen. “He was a real witness — that’s the best word I can think of — to everybody else. He really lived out his own maxim.”

In his 1999 “Letter to the Elderly,” St. John Paul II wrote as an elderly man to the elderly of the world.

“It is wonderful to be able to give oneself to the very end for the sake of the Kingdom of God!” he wrote in this short encyclical.

The encyclical turned out to be a road map for the Pope’s own death.

“The signs of human frailty which are clearly connected with advanced age become a summons to the mutual dependence and indispensable solidarity which link the different generations, inasmuch as every person needs others and draws enrichment from the gifts and charisms of all,” he wrote.

It might be tempting to think of John Paul II as a kind of superhero of old age, who suffered all its attacks and disgraces with spiritual equanimity. Not so, recalled his biographer George Weigel on a visit to Toronto in mid-March.

Weigel, who met often with the Pope, recalled one of the last meetings, when a frail John Paul asked about the then long-retired president Ronald Reagan, an ally of the Polish pope in his quest to erase the iron curtain.

By then Reagan was suffering advanced dementia, unable to recall even that he had been president of the United States. It fell to Weigel to report this to John Paul.

The Pope became very quiet and clearly sad.

“He could imagine no greater burden or cross to bear than not be be able to reflect on his own life,” said Weigel.

For all his courage in facing physical frailty, there was a horror beyond that which even this brave man feared.

John Paul II’s “Letter to the Elderly” is the one papal document McQueen refers to in every presentation she makes to parishes. The value of life lived to the very end, past every frontier, is a vision the ethicist carries with her.

“These are not just wonderful words — though they are wonderful words of encouragement and very spiritual words,” she said. “But he lived them out. He actually demonstrated them personally.”

McQueen is quite sure she would lack the courage to show up in public if her hands were trembling, her speech was a struggle and nothing seemed quite in control.

“These are very normal, human reactions. Most of us would be mortified to be seen looking like that,” she said. “He just took it and did a complete reversal. ‘Here I am. I’m the Pope. I’ve got these afflictions, the same as you. And it’s not keeping me back.’ He was still stomping around the world. Not only that, he was really walking the walk and talking the talk.”

Elected pope in 1978, St. John Paul II never set out to be the pope of death, or the pope of old people. He was the pope who invented World Youth Day.

During his last two World Youth Days, in Rome in 2000 and Toronto 2002, he became the pope who united the generations, who railed against a world in which the young and the old occupy separate and hermetically sealed cultures, each suspicious of the other.

Again more by example than by word, he encouraged the old to place themselves among the young and draw hope from them. He encouraged the young to discover the world of the old and through them how their own youth might one day contribute to the story of a whole life.

The young who learned those lessons from aging Pope John Paul II became the John Paul II generation. Born in the 1970s and 1980s, this generation grew up knowing only one pope.

Weigel believes the deep, cultural and spiritual reform of the Church so heralded under Pope Francis began under Pope John Paul II with the words “New Evangelization.”

“The reform being the re-order- ing of every facet of Church life to mission,” he said.

The American historian and biographer believes Pope John Paul II inaugurated an epochal shift from Counter-Reformation Catholicism to a new era of Evangelical Catholicism.

“Faith by osmosis has no future in the conditions in which we live,” said Weigel. “Christian faith cannot be transmitted genetically, tribally, culturally.”

Karol Wojtyla learned that lesson facing down the Nazis and then the Communists in Poland. And he intended to transmit what he learned from tyrants to the world — faith must be actively, intentionally, consciously lived and communicated.

That is the link between Pope John Paul II and Pope Francis, said King’s University College moral theologian Carolyn Chau.

“One of the things that was part of his personality and part of his witness was an expression of compelling Christianity as a merciful Christianity,” she said.

If it was Pope John Paul II who put Divine Mercy Sunday (April 12 this year) on the Catholic calendar and Pope Francis who has declared a Year of Holy Mercy beginning Dec. 8, 2015, the link between the papacies should be obvious, said Chau.

“I’ve always loved that notion of mercy. I’ve always thought that’s the thing that’s going to welcome people back — the social teaching of the Church and mercy. We all need mercy today,” she said.

In 2000 Pope John Paul II sank to his knees at the Holy Door to St. Peter’s Basilica as he inaugurated the Great Jubilee. He begged for mercy. He confessed the sins of God’s people.

He journeyed from that day through five years, through the suffering that comes to us all, but always in the hope of mercy.