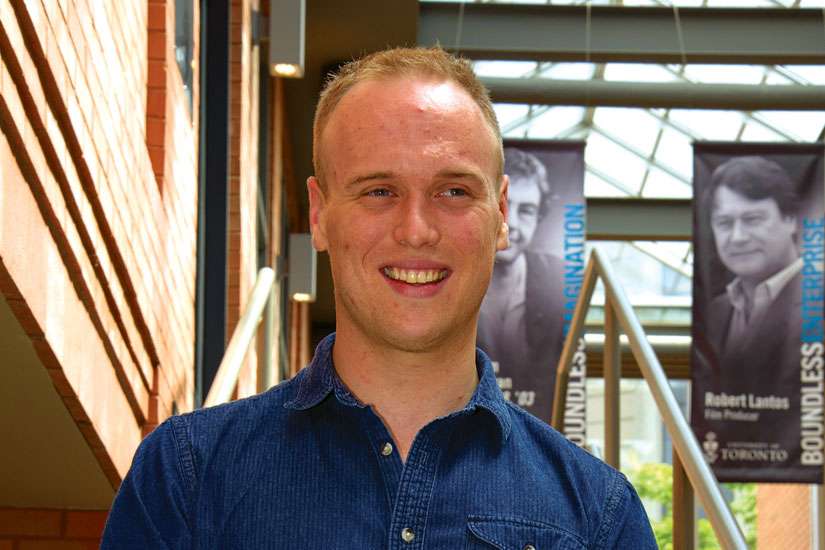

At 27 he’s comfortable talking with the media. He easily marshalls statistics and anecdotes to support his arguments. He speaks convincingly about his spiritual life, his ambitions and his dreams.

Five years ago he was homeless — couch surfing, addicted, aimless, living on the margins just out of reach of anything legitimate or legal.

“Youth make bad choices. This is life. I made bad choices. My friends made bad choices,” he explains. “We’re young. We’re stupid. We think we’re invincible.”

Beckett credits Covenant House with helping him turn his life around.

“It was pivotal. It was actually necessary to the success I enjoy today,” he said. “They just have so many areas of support for youth, whether it be education, health, counselling… It is kind of a one-shop deal — everything under one roof.”

Covenant House is an international agency providing support and services to homeless and at-risk youth. Covenant House Toronto is Canada’s largest homeless youth agency, helping street kids at its downtown Toronto facility in the heart of city just off of Yonge Street.

Things started going downhill for Beckett when he was 14. His parents were divorced and his mother was losing a battle with alcoholism.

“She would move from place to place, taking me along and really kind of uprooting me from any place where I sort of started to make roots,” he said.

When he was 15, Beckett’s mother decided she couldn’t really provide for her son. She called in the children’s aid society and the boy was taken under a temporary

See EARLY on Page 11

care agreement. That turned out to be less of a solution than Beckett might have guessed. A year later the agreement ended and at 16 Beckett had to find somewhere else to live.

At 17 the Oakville kid had his first go ‘round at Covenant House.

“I was pretty intimidated by the whole ordeal — a big downtown shelter… It was just so hard to grasp that I was homeless,” he said.

There are 6,500 homeless youth on the street or camped on someone’s basement couch on any given night in Ontario. Last year the Ontario government pledged to end long-term, chronic homelessness in the province in the next 10 years. The key to fulfilling that promise is going to be our capacity to intervene in the lives of homeless young people and set them on a new path.

“The earlier you intervene the more likely it is that you will be able to effect change,” said Covenant House Toronto CEO Bruce Rivers. “Intervening in situations with youth who are homeless offers you an opportunity to actually interrupt a trajectory that otherwise could lead to chronic and long-term homelessness.”

Rivers served on the province’s expert advisory panel on homelessness in 2015 — the body that convinced the government to declare its intention of reducing all homelessness to one-time, temporary and solvable problems.

“Setting a bold goal and measuring progress is an important element in making real change happen,” Ministry of Housing spokesperson Conrad Spezowka told The Catholic Register in an e-mail.

From the perspective of his own five-plus years of homelessness, Beckett thinks any talk of abolishing homelessness is “more rhetoric than reality.”

“Homelessness can be treated. It can’t be solved, frankly,” he said. “The causes are so vast and so encompassing.”

The province’s plans come with big financial commitments, including $4 billion committed for affordable housing since 2003 and $294 million budgeted in 2016-17 to the Community Homelessness Prevention Initiative. The most recent provincial budget put in $100 million over three years for housing allowances and support services going to people in supportive housing, plus construction of up to 1,500 new supportive housing units. There’s another $10 million dedicated to Ontario’s Local Poverty Reduction Fund in 2016-17.

On average, it costs close to $6,000 ($5,769.23 according to the Ministry of Housing) to rehouse an individual or family who is homeless. Prevention is cheaper at $1,056.34 per household, according to provincial officials.

There’s no better predictor of long-term homelessness than youth homelessness, said Stephen Gaetz, director of the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.

“A high percentage of adults who are homeless had their first experience of homelessness when they were teens,” he said. “We wait for young people to pull themselves up by the bootstraps. The problem is that when you do that, if you let any young person languish in homelessness, their health declines, they experience nutritional vulnerability, they’re more likely to be ill or injured, their mental health declines, there are higher rates of depression and suicidality, their risk of exploitation goes through the roof because there’s a lot of creepy people out there.”

At Covenant House, Rivers’ own research has shown that homeless youth are up to 40 times more likely to die young than their peers.

Youth homelessness is both different and the same as adult homelessness. It’s different in that the driving factor is family dysfunction and not simply poverty. Half of them come from middle- and upper-income households. Like adult homelessness, the results of youth homelessness are almost always best measured in terms of health. More than a third of the kids at Covenant House have mental health issues. Covenant House teams up with St. Michael’s Hospital’s inner city health department to extend basic medical care to kids who are undernourished, sick and at risk.

There are also new challenges in youth homelessness. While there have always been girls in the sex trade living at the mercy of pimps and ultimately organized crime, today the trade in human flesh has been amped up by technology.

“It used to be much more visible. Kids would be on the street, visibly prostituting,” said Rivers. “Today, that’s not necessarily the case with the evolution of the Internet and social media and all of these other avenues.”

Covenant House is trying to raise $10 million over five years to launch an urban response model to protect the girls. It will have to come mostly from donations. Only 20 per cent of Covenant House programming is funded by government. About $600,000 a year from the Archdiocese of Toronto has been a stable, sure source. But welcoming 250 young people a day, running a school, a housing program, a counselling service, a clinic and more is very expensive.

“It’s the donor dollar that has made Covenant House what it is today,” Rivers said.

What Covenant House is today is far more than just a shelter. This is an institution in the heart of the city that deals with a problem no one else wants to think about. Shelters are for emergencies. More than 3,000 kids a year, every year, is more a fact of life than an emergency.

“Providing people with three hots (meals) and a cot — however well meaning that is — it really doesn’t address the issues,” said Gaetz. “They need housing, which is not the same as an emergency shelter bed. They need adult support and mentoring. They need a chance to recover if they’ve experienced trauma. They need safety. They need a chance to get back to school. We have to stick with them for a long time, until they’re stable.”

Turning the corner on youth homelessness begins with thinking of young homeless people as children, minors, who don’t deserve the suffering they’ve found in life.

“We demonize other people. We think of them as criminals, or delinquents, or bad kids,” Gaetz said. “We’re here to help people grow into adulthood in a healthy way, in a safe way — and give them the support they need for as long as they need it, not thinking, ‘Oh great, here’s a cot, here’s a bologna sandwich. You should be thankful.’ ”

Nobody should be surprised that people who went through homelessness when their peers were working on high school yearbooks and organizing the school dance aren’t quite ready for independence at 21, said Becket.

“You need to be a little more merciful, perhaps extend a little more grace,” he said. “It’s a whole new ball game. Everything has changed.”