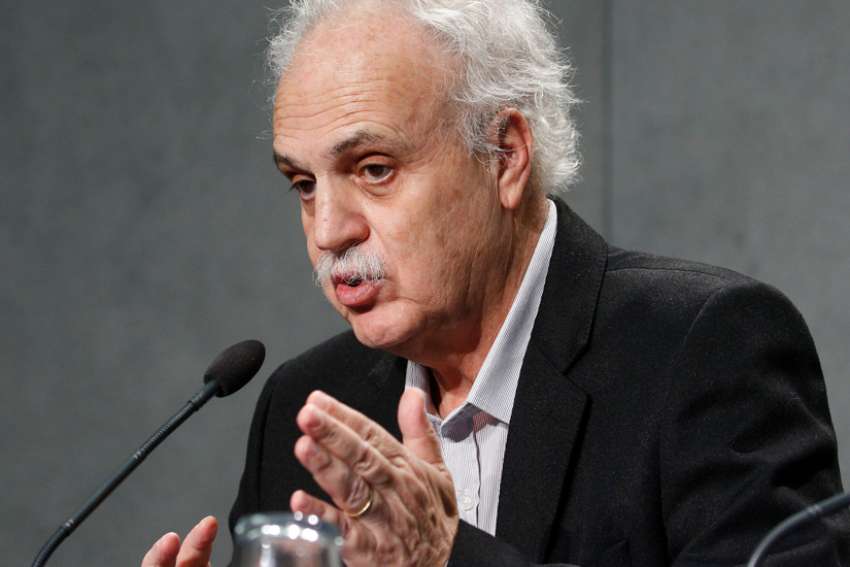

In his four-minute presentation to the synod on Oct. 15, economist Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University called for a common global plan for the forest and the peoples who live there. He proposed increased investment by the world's countries to preserve Amazonian forests, the creation of an international scientific panel, and action by governments to curb deforestation.

A week earlier, Brazilian climate scientist Carlos Nobre proposed taking advantage of modern technologies of what economists call the "fourth industrial revolution" to create a "bioeconomy" of sustainably produced items that would keep the forest standing. Processing Amazonian fruits and nuts, as well as crops like cocoa, can be more profitable than ranching, which is one of the main drivers of deforestation, he told Catholic News Service in a telephone interview.

Both proposals reflect a series of recommendations made in an essay titled "Scientific Framework to Save the Amazon," which was prepared for the synod by more than 40 scientists, including Nobre. The essay cites Pope Francis' encyclical "Laudato Si'" and calls for countries to adhere to the 2015 Paris climate agreement.

It also presents the proposal of developing "bio-industries" to produce foods, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and other products using forests as a source, and calls for companies to ensure that any products they purchase are sustainably produced.

Several synod participants worried that such proposals could sideline indigenous people from decisions about development, especially if their land rights are not secure. Local communities in the Amazon must have the power to decide what kind of development they want, they said.

The scientific framework essay links the proposed bioeconomy to concept of integral ecology described in "Laudato Si'." Critics, however, said that it put a price on nature and created the risk of privatizing forest resources that communities now view collective goods.

Others noted that although outside experts invited to the synod speak from their own perspectives, the rights of indigenous peoples have been a constant theme during individual presentations and small-group discussions.

People who questioned the proposals said Sachs and Nobre did not mention indigenous people's right to be consulted about projects affecting them, which is enshrined in international treaties. They also worried that outsiders could use development projects to benefit themselves instead of the communities from which forest products are taken.

Nobre told Catholic News Service that the proposal is still new and that the scientists involved have not conducted a formal consultation with indigenous groups. He said the idea is for communities to operate their own businesses and not to open the door to outsiders.

Although she did not refer directly to those proposals, Yesica Patiachi Tayori, a Harakbut woman from Peru, told journalists Oct. 16, "We don't want (the synod) to end in a mercantilist discourse."

Patiachi, who made that remark at the daily press briefing, was one of the speakers who addressed the pope in January 2018 during his encounter with indigenous people in Puerto Maldonado, Peru. On that occasion, she asked him to help her people defend themselves against "outsiders who see us as weak and insist on taking our territory away from us in different ways."

Inside the synod and at parallel events nearby, indigenous people have called for church leaders especially to support their efforts to obtain official rights to their territories. When they do not have legal title, they risk losing their land to land speculators, private enterprises like mining companies, or outsiders who engage in illegal logging, wildcat gold mining or other illicit activities.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has halted the demarcation of indigenous lands even where the process was underway. In Peru, hundreds of indigenous communities await titling.

Amazonian indigenous groups hope that the pope, as an internationally known figure, will amplify their demand for respect for their rights and territories, Gregorio Diaz, president of an umbrella organization of Amazonian indigenous groups, told CNS.

"The synod has to issue a strong message to governments that are making decisions (that affect) indigenous peoples," he said.

At a news briefing Oct. 14, he called for the church to stand up for indigenous people who risk assassination or who face criminal prosecution and imprisonment for defending their territories.

He also asked the church to help indigenous people "talk with the new gods of the developed world, (such as) Google, the International Monetary Fund, the European Economic Commission and the World Bank," and to encourage Amazonian governments to "sit down and talk with us."

Amazonian governors are expected to attend a meeting at the Vatican Oct. 28, Brazilian media reported.