This exhibition gathers together more than 100 finished works in various media as well as a fascinating array of source materials such as notebooks, letters and preparatory sketches and photographs. These works and supporting materials are arranged in different quadrants of the exhibition space that address the four great organizing themes of light, spirit, time and place. Taken together the viewer comes away with a very vivid appreciation of the tragically short life of this driven and restless artist.

That Chambers is less well known than many artists whose works, frankly, are not as accomplished is probably attributable to his too-early death from leukemia at the age of 47 before he could imprint himself on the national consciousness as an institution. In his hometown of London, Ont., where a school is named after him, he has attained such status.

Also discouraging broad recognition is that Chambers worked in so many radically different styles and media. There are early impressionist and surrealist works, and his infatuation with film led him to make a half dozen or so collage-like movies (which I find doomy and pretentious though they have a following) and a series of “silver paintings” (which don’t do much for me). In these, he worked with aluminum paint that, like a photographic negative, can either reveal an image or reflect opaque light depending on where you stand.

Deservedly, I would say, Chambers is best known for about a half dozen very large realist oil paintings — titled 401 Towards London, Sunday Morning No. 2, Victoria Hospital, Diego Sleeping No. 2, Lake Huron No. 4, Meadow — which were executed in a style he called “perceptual realism.” He created this tag largely to distinguish his art from the faddishness of so-called “Op Art” (celebrated for being as realistic as a photograph), which was fashionable in the late 1960s and early ’70s. Certainly Chambers worked from photographs in developing these great works but with their exquisite structure and stillness and radiance, there’s something much finer in play here than mere photo-likeness.

Chambers began to draw and paint while still in elementary school. From his early teens onward he knew that he wanted to be an artist. While his earliest works are understandably derivative, even canvases from his teenage years show great potential and he was often awarded prizes in group exhibitions and competitions. At the age of 16 he enrolled in art at London’s H.B. Beal Secondary School, then one of the finest visual art programs in the country, where he was able to devote nearly all of his time to painting. But he knew his vision wouldn’t really gel until he moved out of his hometown.

After short terms of living on his own and painting in Quebec City and Mexico City, Chambers took the money he’d earned from working three different menial jobs simultaneously and headed to Europe. He eventually landed in Spain, where he studied and worked for eight years, met his wife-to-be and converted to Roman Catholicism.

Toward the end of his life Chambers reflected on his time abroad, saying, “There were things I tried to do and couldn’t do, and I didn’t think that what I was looking for was to be found in Canada or the U.S.A. . . . I was not interested in style as such . . . I wanted something much more elemental; something like basic training, a visible standard that was not made distinctive by personal vision and accomplishment. I wanted a realistic standard of ability which was craft and not art.”

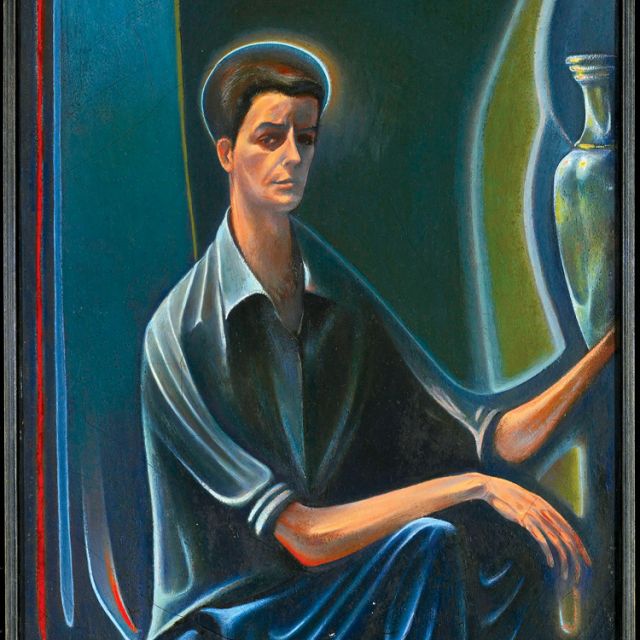

His conversion to Catholicism in 1957 was also partly driven by his desire to push himself harder and to hone his skills. “Catholicism to me was one way of putting a harness on the horse and getting the animal to work for an end. It was a way of harnessing a lot of energies, a lot of anxieties.”

Everything in Chambers’ life served his art, even his illness. Talking with the writer Susan Crean shortly after being diagnosed with leukemia, he said it helped him to focus and get down to work. “To have all the seats in the theatre to choose from provides you with a problem, eh? But if one seat is left, you jump into it and watch.”

Chambers’ faith would ebb and flow over the last 20 years of his life. Back at home in London with his wife and two sons and (together with his artist friend Greg Curnoe) spearheading an incredibly fertile explosion in the local art scene, Chambers was so fully engaged that his Catholic observances lapsed.

Diagnosed with leukemia in 1969 and told he had perhaps a year to live, he rejoined the Church and entered into a profound correspondence with Fr. Ambrose McInnes, a London friend from his youth who lived with the Dominicans in New Orleans and occasionally celebrated Mass at Chambers’ home.

Chambers lived with his fatal diagnosis for almost nine years, his stamina steadily dropping. During that period he produced much of his very best art, for which he was paid larger and larger sums, setting records for prices received by a living Canadian artist. Most of that money was socked away to provide for his family after he was gone. Some of it was spent on erratic trips to the United States, Mexico, England and India to visit clinics, gurus and assorted quacks in search of a magical cure.

The very last piece Chambers worked on was a painting of a subject McInnes had brought to his attention — a British army officer turned priest named Henry Edward Dormer, who is London’s only candidate for sainthood.

(Goodden is a freelance writer in London, Ont.)

AGO exhibit showcases life of Catholic artist Jack Chambers

By Herman Goodden, Catholic Register SpecialThe Canadian artist Jack Chambers (1931-78) is the subject of a major retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario that runs until May 13 in the Signy Eaton Gallery. “Jack who?” you may wonder.

AGO director Matthew Teitelbaum acknowledges in the first paragraph of his foreword to this show’s catalogue that Chambers’ “work has all but disappeared” from the national consciousness and that this exhibition is “a project of repositioning,” to pull “back into the spotlight an artist indispensable to a history of the image in 20th-century Canada.”

Please support The Catholic Register

Unlike many media companies, The Catholic Register has never charged readers for access to the news and information on our website. We want to keep our award-winning journalism as widely available as possible. But we need your help.

For more than 125 years, The Register has been a trusted source of faith-based journalism. By making even a small donation you help ensure our future as an important voice in the Catholic Church. If you support the mission of Catholic journalism, please donate today. Thank you.

DONATE