He studied to be an ordained Lutheran minister but converted to Catholicism and was ordained a Catholic priest. He began as a left-wing activist of the 1960s but spanned the political spectrum to make his mark as a neo-conservative.

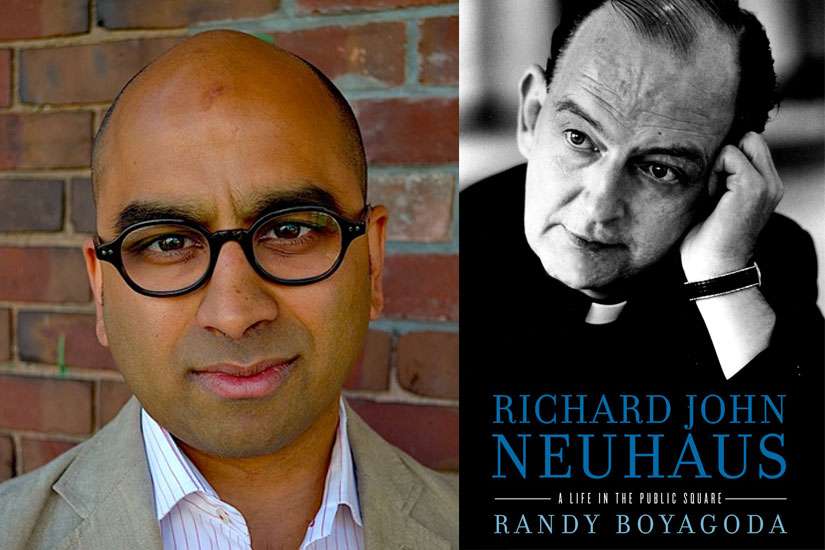

Neuhaus, a Canadian by birth, died in January 2009. His death received nationwide coverage in the United States but hardly any note was taken of it in Canada. In an article for the August 2009 issue of The Walrus a few months after Neuhaus’ death, Ryerson University American Studies professor Randy Boyagoda argued that Neuhaus was under appreciated in Canada.

He attributed this to Neuhaus’ “unapologetically religious cast of ideas and actions.”

Boyagoda wrote the article to try to correct this lack of interest and introduce Canadian readers to someone he described in the magazine America as “arguably the most influential Canadian-born U.S. intellectual of the past 50 years.” This biography followed naturally.

As a Catholic priest and before that as a Lutheran minister, Neuhaus wrote prolifically and preached from a religious perspective.

But the issues that interested him were almost exclusively American and political.

I would argue that Boyagoda’s explanation for Neuhaus’ low profile in Canada is not necessarily sufficient.

Neuhaus protested the Vietnam War and supported the civil rights movement in the 1960s, and warned of the dangers of the Christian religious right during the 1980s. Then he staunchly defended the Bush administration’s role in the aftermath and response to the attacks of 9/11, and was an advisor to both Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

He covered the spectrum, as it were, from far left to far right over his lifetime but the particular political issues he was interested in did not have much resonance in Canada.

What is interesting about Boyagoda’s work is his attempt to explain Neuhaus’ political shift from left to right. There are hints in his early life of the conservative side that would eventually predominate.

There was the influence of his father, Clem, who was himself a Lutheran minister with conservative views. Was Neuhaus’ early left-wing political stance an attempt to prove he was not his father? Interestingly, Neuhaus’ politics did shift further to the right after Clem’s death.

Another possibility, which Boyagoda seems to favour, is that Neuhaus’ transition reflects the development of a new generation of Americans. He notes that a number of other future neo-cons — such as Paul Wolfowitz — were part of the same protest marches in the 1960s. What is lacking, of course, is Neuhaus’ own answer to the direct question.

Boyagoda writes that, “Neuhaus was always working to develop and advance a ‘public philosophy’ that justified religion’s role in the right ordering of American life.

“At the same time, he was always seeking to win the most politically influential audience possible for his own vision of what that right ordering would involve, whether this meant an end to an unjust war, racial discrimination, abortion or embryonic stem-cell research.” This philosophy would hold regardless of which political party or views he was supporting at the time.

Boyagoda tackles his subject with thoroughness and thoughtfulness and provides the reader with a balanced yet critical analysis of a man of undoubted influence in American political and religious life in the latter part of the 20th century.

A particular strength of this book is Boyagoda’s ability to point out Neuhaus’ contradictions and human failings, as well as his strengths and his legacy. He was a man of God, first and foremost, and much more than the right-wing neo-con his critics deride.

(Maria Di Paolo is a Toronto freelance writer.)