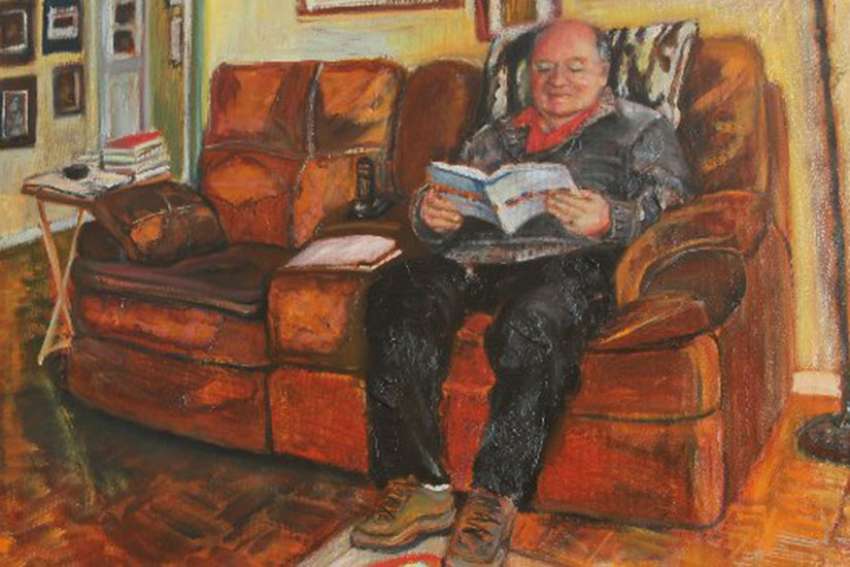

Yet Fr. John Emmett Walsh’s cheerful serenity and optimism run throughout his memoir of a lifetime of pastoring in Montreal. Walsh celebrates the changes brought by the Second Vatican Council.

He follows Gregory Baum’s incarnational and panentheistic approach. He defines panentheism, not to be confused with pantheism, as “a sense of God being in the world and the world being in God.”

Walsh was ordained in 1966, around the time of Humanae Vitae. He characterizes his early priestly years as a baptism by fire. The Church moved from a transcendent to an incarnational understanding of our life in the Spirit.

We went from a vertical, cultic orientation as Catholics to a horizontal, whole-people-of-God perspective. Fully supportive of this, Walsh takes this new reality to mean that “we are to be priests in a Church of the poor, for the poor — a Church that is hurting, dirty and out in the streets.”

While Walsh clearly takes a social justice perspective on the Church’s work, he also writes of larger experiences. Reflecting back on studying Hebrew in Israel, he observes, “I was struck by the fact that even though Jesus was born, lived, preached and did His ministry in the Holy Land, the Christian faith is not rooted in the land of Israel in any comparable way.”

He was likewise struck by how the “Jews are a people,” yet Catholics do not see themselves in the same way. He laments, “How long will it take for Catholics to recognize that we are saved as a community and not as individuals!”

This critique against individualism strengthens the book by giving support to his social justice concerns.

Yet Walsh takes a strange, even puzzling, attitude to the failure of the Church to hold onto Catholics.

“The Risen Christ left behind an empty tomb. The success of the Council can be seen in the empty churches as sure signs that God wants us to discover the signs of our time and respond with the Spirit that blows where she wills, in the world.”

This is nonsense. Walsh fails to address enormous failures over the last 50 years. While Walsh chides the pre-Vatican II Church as comfortable and inward looking, throughout the book one has the impression that he too has become comfortable with closed parishes and a disbelieving public. He too has become inward looking in the sense of remaining in his own community of like-minded thinkers. Empty churches are indeed a sign of failure, and his blasé attitude fails to suit the Gospel’s urgent, evangelical character.

The supposedly terribly rigid, pre-1960s Church he has turned his back on enjoyed high status and full pews. While this is not in itself the Church’s vocation, a deeper analysis of why parishes emptied in his home province Quebec and around the Western world after Vatican II would have given greater depth and honesty to Walsh’s autobiography. As it stands, given this unacknowledged elephant in the room, the book remains half accomplished.

The author portrays himself as having seen and played a part in the revolution that rocked the Church in the post-Vatican II years, but Walsh seems unwilling to question anything he stands for.

(Welter is a Canadian freelance writer living in Taiwan.)