For example, I had not realized that in the American civil war most evangelicals sympathized with the North and favoured abolition. The redneck Southern evangelical, stereotypically portrayed by the media, is largely a fantasy figure — at least until the late 20th century.

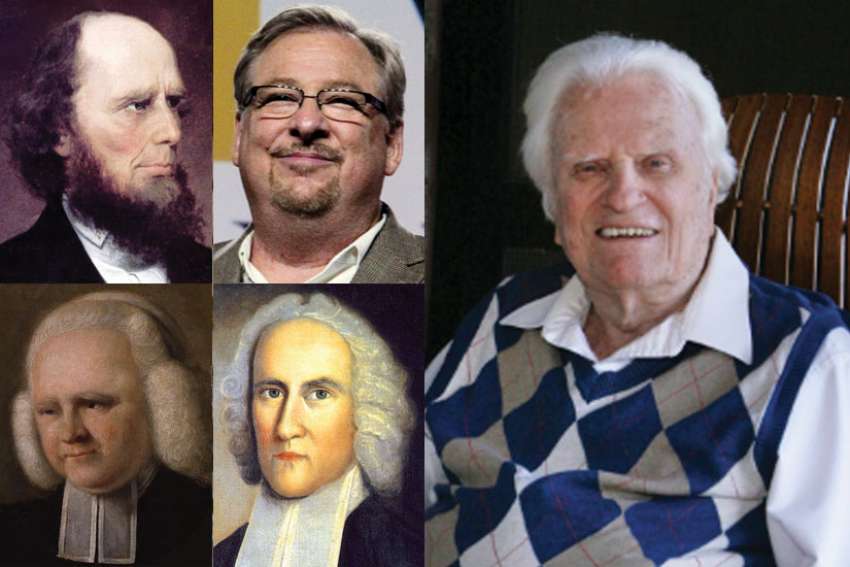

The term “evangelical” (from the Greek “evangelion,” meaning good news) denotes those Christian proselytes influenced by the “great awakenings” of the 18th and 19th centuries. The first great awakening in New England is associated primarily with Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield. The second awakening spread evangelicalism in a (now) independent America and is associated primarily with Charles Finney (who called slavery “a great national sin” and refused communion to slaveholders).

When ill-heath forced Finney to leave the preaching circuit, he took up a teaching position at Oberlin College in Ohio and transformed it into a centre of evangelical Christianity. Oberlin then became the first U.S. college to admit black and female students. Henceforth, evangelicals followed Finney’s lead and built Bible schools, seminaries and Christian conference centres at locations across America.

Northern evangelicals pioneered in the development of asylums, soup kitchens, schools for the deaf, tuberculosis sanitaria and advocated for prison reform. They formed missionary and tract societies. At a time when Americans apparently drank about four times as much alcohol per capita as today, evangelicals founded Temperance societies.

They were pioneers of adult literacy (how else could one read the Bible?) and educational reforms. In 1828, some evangelicals formed the American Peace Society and promoted pacifism.

So what happened? How did a progressive movement evolve into militant anti-modernism? Putting it another way, how did Charles Finney morph into Elmer Gantry?

Well, several things happened: modern biblical scholarship, Darwinian evolution, industrialization and urbanization. By 1920 half of Americans lived in cities or towns. Then, in 1925 liberal theology and evangelicalism (or more accurately, its misshapen offspring, fundamentalism) engaged in hand-to-hand combat in a courtroom in Dayton, Tenn., in the Scopes “monkey trial.”

In popular mythology — fortified by the wildly inaccurate Broadway play and Hollywood movie Inherit the Wind — liberalism emerged triumphant. Fitzgerald writes: “The trial had turned fundamentalists into outsiders within a dominant liberal Protestant and secular culture.”

For a couple of decades, American evangelicalism went underground. Then in 1949 a handsome young man from North Carolina, Billy Graham, burst on the scene with a successful eight-week crusade in Los Angeles attended by 350,000 people. Randolph Hearst instructed his chain of newspapers to “puff Graham” and evangelicalism was in public view again.

Fitzgerald devotes about a third of her 700 pages to what might be called (although she does not use the term) the “Billy Graham era” from, say, 1950-1990. “No American evangelist before or since,” she writes, “achieved the success that Billy Graham did in the middle years of the 20th century. Indefatigable and constantly in motion, he evangelized on five continents and with the advantages of radio, television and airplanes spoke to more people than any other preacher before in history.”

Fitzgerald depicts brief but instructive portraits of other major evangelical figures of the late 20th century: Jerry Falwell, Oral Roberts, Pat Robertson, Jim Bakker and several others.

She describes the transformation that occurred in the 1980s when evangelicals decided to pursue overtly political ends and created organizations to oppose abortion, homosexuality, drugs, pornography and secular humanism. The most notable of these were the Christian Coalition and Focus on the Family.

This collective effort gave rise to what became a pejorative term — the Christian Right. In retrospect, the reader is struck by how utterly ineffectual all this was. Even in 1980, when Ronald Reagan was elected president, careful analysis of the voting demonstrates that the Christian right played an insignificant role in the outcome. The organizations faded away (Jerry Falwell shut down the Moral Majority in 1986) and none succeeded in altering, or even visibly delaying, the one-way liberal ratchet that transformed America into the secular wasteland perceived today by many evangelicals.

Perhaps, then, it is not surprising that the current crop of evangelical leaders — people like Tony Campolo and Rick Warren — seem to have made their peace with modernity. Not only do they use current technology and social media to communicate but what they communicate seems more about poverty, climate change, gender issues and racial injustice as about the traditional preoccupations of evangelicalism. Though few of them might willingly admit it, many contemporary evangelicals fit quite comfortably within Barack Obama’s Democratic Party. In 2009, Warren declared the Christian Right dead.

Some evangelicals worked hard in a failed effort to defeat Obama in 2012. After that failed, they pretty much gave up. Albert Mohler put it this way: “Millions of American evangelicals are absolutely shocked by not just the presidential election, but by the entire avalanche of results …. It’s not that our message — we think abortion is wrong, we think same-sex marriage is wrong — didn’t get out. It did get out. It’s that the entire moral landscape has changed. An increasingly secularized America understands our positions and has rejected them.”

The subtitle of this book is The Struggle to Shape America. So where, in the era of President Donald Trump, do evangelicals stand? Since the late 1990s membership in evangelical churches is in decline. Roughly one in four Americans self-identify as having no religious affiliation.

In 2014 the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in every state. Legalized euthanasia is upon us. Evangelicals today are scattered, divided, demoralized and largely impotent. At best they are a splinter in a Republican Party that is currently being refashioned in the image, not of a previous Republican president or historic conservative thought or practice, and still less of evangelicalism, but of a demagogue.

(Hunter is Professor Emeritus in the Faculty of Law at Western University in London, Ont.)