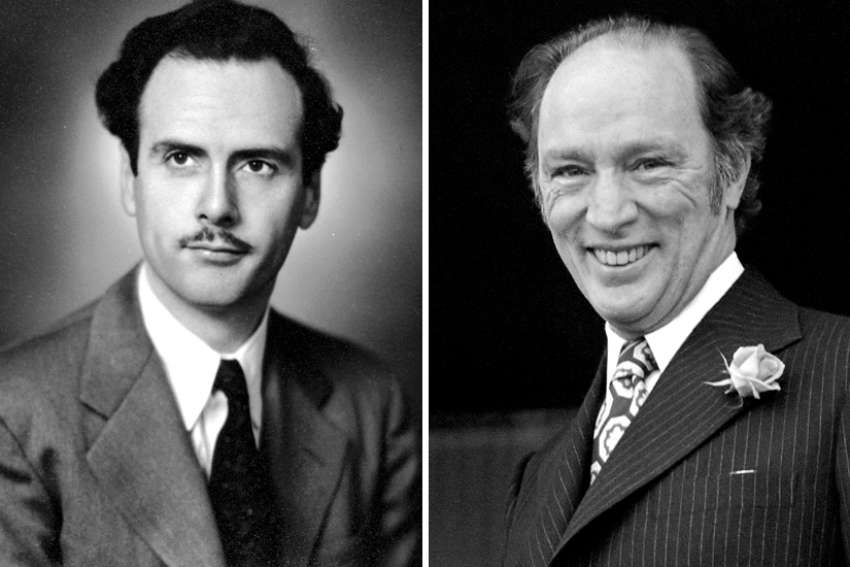

In Been Hoping We Might Meet Again: The Letters of Pierre Elliott Trudeau and Marshall McLuhan, Elaine Kahn presents readers with over a decade of correspondence between these two famous Canadians. Pierre Elliott Trudeau (1919-2000) needs little introduction. Canada’s most famous prime minister, as Kahn notes repeatedly, was a federalist who legislated bilingualism, fought sovereigntists in Quebec and established a Canadian constitution along with a Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980) is today the lesser known of the two. Born in Edmonton, he completed a doctorate in literature at Cambridge and spent most of his academic career at the University of Toronto’s Department of English. In the 1960s he rose to global prominence as a ground-breaking thinker on media and its effects on peoples’ thinking and behaviour.

Even if you have not heard of McLuhan, you are probably familiar with phrases he coined, such as “global village” and the “medium is the message.” One of McLuhan’s key insights was that new media create new culture and, literally, reshape how humans think and act. A medium is not just a means of conveying something, rather the medium is very much the actual content being conveyed.

McLuhan’s ideas, coupled with his penchant to use aphorisms rather than systematic arguments, made him a controversial figure. Interest in McLuhan revived in the 1990s, driven in large part by his prescience. It is astonishing how accurately McLuhan described our Internet and social media reality.

At the heart of this short book are the letters written from 1968 until McLuhan’s death in 1980. Kahn accompanies the correspondence with explanatory notes: some give details about people or events mentioned in the letters, others are more editorial in nature.

For Kahn, the two men are important because of the way they perceived and positioned themselves in a globalizing world. McLuhan initiated the correspondence, which touched on the subject of media in general and various, particular forms of media. He was also interested in Canadian identity, religion, Canada-U.S. relations, image in politics.

He advised Trudeau on what kinds of media appearances would be most advantageous to the PM: “The very cool corporate mask that is your major political asset goes naturally with processing of problems in dialogue rather than in the production of packaged answers,” McLuhan wrote.

As a historian, I value having archival sources published. Nevertheless, this particular volume of correspondence makes for a curious book: I am not sure who the intended audience is.

This is not a text for the uninitiated. Kahn’s introductory chapter seems to echo McLuhan’s style as she evokes ideas and points to connections both in the historical material and with present day issues, but avoids any rigorous analysis. Kahn is clearly a fan of McLuhan and, even more so, of Trudeau, and thus does not approach either figure critically.

The book, a revision of Kahn’s 2017 doctoral thesis in global affairs, is published by Novalis, “Canada’s Religious Publisher.” This review is for The Catholic Register. It is these two media that compel me to comment on religion, which, though present, seems peripheral to the correspondence.

Trudeau and McLuhan are significant Canadian Catholics. The politician was a cradle Catholic. The professor was a convert to the faith. Neither wore his faith on his sleeve, yet both were deeply shaped by Catholicism, an issue scholars continue to study.

The liturgy punctuated their lives: they attended Mass regularly. Close friends attest to the faith of both men. Though there is no sustained discussion of Catholicism in the letters, McLuhan makes some interesting observations. The most intriguing is his structural analysis of Vatican II, whereby he suggests the Council has to be understood not just as an event shaped by those who participated in it, but also as a product of and a response (though unconscious) to the rise of new media, particularly television.

While McLuhan provides new insights into the ways in which changes in media affect individuals, it does not seem that he could always take his own medicine. He claimed that, “Since the press lives on advertising, and all advertising is good news, it takes a lot of bad news to sell all this good news. Even the good news of the Gospel can only be sold by hellfire. Vatican II made a very big mistake in this matter as in other matters.”

Was McLuhan revealing himself as a victim of the loss of identity that changes in media cause? Was his visceral reaction to the Council an expression of the discomfort, tribalization and even violence that accompany these changes to identity — changes McLuhan so presciently described?

(Cuplinskas is Associate Professor of Christian history at St. Joseph’s College, University of Alberta.)