Passion Sunday, April 14 (Year C) Isaiah 50:4-7; Psalm 22; Philippians 2:6-11; Luke 22:14-23:56

What is the difference between an ordinary person and one who is a prophet, teacher or saint?

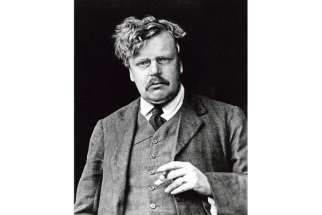

Chesterton a ‘prophet of our times’

TORONTO – Although much of his work relies on long outdated references, there is still an inherent value to reading G.K. Chesterton’s essays, novels and short stories for Canadians today.

God’s power manifests when we surrender to Him

Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time (Year A) July 5 (Ezekiel 2:3-5; Psalm 123; 2 Corinthians 12:7-10; Mark 6:1-6)

Who could blame Ezekiel if he had refused the role of prophet? The job description did not sound promising or encouraging. He was being given a thankless task that was doomed to failure. His mission was to prophesy to Israel, which sounded harmless enough, but the divine voice painted a very unflattering portrait of the nation. Impudent, stubborn and rebellious are not words that would give one hope of success.

VATICAN CITY - The Vatican’s semi-official newspaper blasted a series of cartoons of Islam’s Prophet Muhammad as “blasphemous” but also condemned the “mad and bloodthirsty” extremists who opened fire at a Texas exhibit of the cartoons.

God’s love is eternal always

Fourth Sunday of Lent (Year B) March 15 (2 Chronicles 36:14-17a, 19-23; Psalm 137; Ephesians 2:4-10; John 3:14-21)

A view from the Old Testament needed to understand Jesus

Burn your self-help books and follow the Divine Word to be happy, says Fr. Robert Barron in his new six-part study program Priest, Prophet, King.

St. Hildegard’s living light

TORONTO - St. Hildegard of Bingen was a mystic prophet who challenged the status quo of her medieval society with her vast written legacy of medical and theological texts, musical repertoire and a penchant for challenging her superiors in the Church. One could be tempted to argue that Hildegard was the original feminist.

Now, in addition to her being named a Doctor of the Church on Oct. 7 (only the fourth woman to receive the recognition), she can also add film and theatre star to her impressive resume.

Linn Maxwell, internationally recognized mezzo-soprano, is coming to Toronto on Oct. 23 and 24 with her one-woman show, Hildegard of Bingen and the Living Light, which has also been recently released as a film adaption. The show tells the story of Hildegard and her mystic visions which ultimately led her to leave a profound mark on the history of the Church.

“She (Hildegard) kind of directed the whole project — I am convinced that this wonderful saint has been behind this the whole time,” said Maxwell of her show, which has now reached audiences across the globe. “When I was writing it... I always felt like there was this little voice behind me saying, ‘no, just tell my story, be truthful, and be chronological.’ ”

In her production, Maxwell has interspersed the life story of St. Hildegard with her original compositions, which she sings and accompanies on traditional medieval instruments.

“It was a journey... I chose the chronological order of things, and I chose her words as much as possible,” said Maxwell. “The first hurdle was choosing the seven songs that I use in the play — the music should carry the action forward.

“The next challenge was to do dialogue and then a song, and then dialogue again so that it’s seamless and organic.”

Born into a noble family in present-day Germany, Hildegard’s parents had a religious disposition and promised their child to the service of God. Invested with the habit of St. Benedict, according to the Catholic Encyclopedia, she was appointed superior of her order in 1136, eventually moving the order to Bingen on the left bank of the Rhine.

In her journey to capture the spirit of Hildegard’s story, Maxwell found herself in Bingen, Germany, and eventually Disibodenberg where the ruins of Hildegard’s first monastery are located.

“It was just incredibly amazing. I was there all alone — I think she arranged it so that there would be no one else there. I stayed two or three hours until it got dark and I finally had to leave,” said Maxwell. “I just felt her presence... I felt like, ‘ah, I’ve gotten in touch with her.’ ”

The challenge in performing the show comes not only from Maxwell’s embodiment of such a powerful and unusual woman, but from the interpretation of musical texts that are devoid of rhythmic notation.

“The Sequentia recordings were somewhat of an inspiration for me,” said Maxwell, who is a colleague of Ben Bagby, director of the Sequentia Ensemble for Medieval Music. “You go with the flow of the phrase,” Maxwell added of her own interpretations.

Hildegard’s music holds a certain relevance today, as it defied conventional structures of the time to some extent.

“Hildegard was unusual. She was an extraordinarily learned person at the time,” said John Haines, a professor of history and culture at the University of Toronto and a scholar of medieval music at U of T’s Centre for Medieval Studies.

“It is chant — it looks like plain chant in that it’s just one melody, but, generally speaking, compared to... most of the chants that survive from that time period, it’s very wide in range,” said Haines. “Her music is very compelling... it’s difficult to perform too.”

Haines notes that only about one per cent of the population at the time would have been able to write, so the fact that Hildegard’s compositions survive, and are written by a woman, is somewhat remarkable.

Additionally, he points out that Hildegard embraced unusual choices in modality and in the textual and musical relationship, where she employs the use of melisma more than her contemporaries may have done.

“Hildegard tended to favour this one mode on E, which features a half-step from the first tone to the second — it’s very easy to recognize,” said Haines. “Which for us gives a kind of eerie sound to her music, but it’s a very specific type of sound that makes it even more idiomatic.”

Maxwell said Hildegard’s message is “more urgent today than ever before,” and perhaps so; her position as Doctor of the Church means that her theological contributions are still teachable and important today.

“She was a trumpet, proclaiming the word of God,” said Maxwell of her muse and inspiration. “When I’m done, hopefully the audience will know Hildegard.”

For more on the Toronto dates for Hildegard of Bingen and the Living Light or to purchase the film, go to www.hildegardofbingen.net.