Lougen had found himself drawn by the love of God to become a missionary at an early age. He said one of his first inklings of that love occurred when he was three or four years old, when he walked into his father’s room to kiss him goodnight. He found his father, “a big, strong policeman, who had been a Marine in World War II,” kneeling at his bedside, saying his prayers.

“That image touched me,” he said. “It spoke to me of God.”

The desire was reinforced during his high school years when he attended a school run by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate and heard stories of the missions in Brazil and Japan.

Lougen said he realized, “That’s what I want to do. I want to be a priest for the poor. That’s how I want to give my life.”

So in 1978, after he was ordained a deacon, Lougen got his wish and had his first experience in the mission field, in the favelas of Brazil.

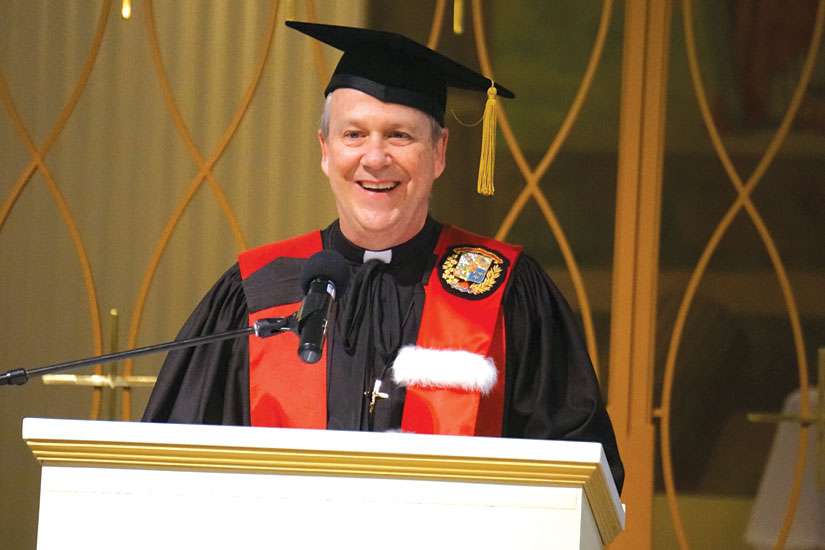

The culture shock he experienced had nothing to do with the food or the people he met. “It was the Church that was so different,” he said. The Buffalo, N.Y., native — who was in Ottawa recently to receive an honorary doctorate from Saint Paul University — went to his first Mass, which was celebrated in Portuguese. Right after Mass, the people moved all the chairs into a circle. Some of the men were smoking in the church and talking about arranging a workers’ strike.

“I’m at this first Mass and I’m shocked! What’s going on here?” said Lougen, who is now Superior General of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate.

But he came to realize the Church represented the only place where people were free to talk about Brazil’s military dictatorship and how to change it.

“Little by little I began to see this wonderful church welcoming the poor, and supporting the poor on a journey looking for freedom for the people of the country,” he said. He was in Sao Paulo, a city of 18 million, where the poor lived on the margins, in favelas where there were only dirt paths, no sewage or running water.

People were organizing to try to get better housing, electricity and generally improve their lives, he said.

At the time the price of rice and beans was skyrocketing so a group of mostly women organized a demonstration, taking their empty pots and spoons to the plaza by the cathedral, with plans to beat the pots at a prearranged time. This crowd of mostly women encountered tanks, police with shields and hundreds of police dogs, he said.

As the people entered the plaza, the police started hurling gas bombs into the crowd. The cathedral was normally closed at that time, but its doors were flung open and tens of thousands of people squeezed inside for protection from the police.

“The Church was an ark of salvation quite literally,” he said.

That image reinforced in his mind the notion of “The Church is a Church of the poor, with the poor, for the poor,” he said.

Lougen returned to Washington, D.C., to be ordained a priest before returning to Brazil as a missionary in the Sao Paulo Oblate province. He found himself inspired by the faith he discovered among the poor, even those with terribly broken lives.

Not long after his return to Brazil, police murdered 12 young men in the favela, but the families were too afraid to bury them for fear the police would target them, too, he said. So a woman called Maria Baixinha, “Little Maria,” went door to door collecting what little she could, and eventually was able to buy the coffins for the men so Lougen could celebrate their funeral. It was an act of courage on her part and on the peoples’ part to attend this funeral, he said.

“I asked her, ‘How do you keep going?’ ” considering she was living in dire poverty, with problems in her family, surrounded by violence. “It’s the Holy Spirit, don’t you know!” she replied.

The people in the favelas “looked after us,” he said. When he had problems with his back, they took over the house, cooking and cleaning. There were beautiful relationships among the people, even if by most standards they would not be considered good Catholics, not married in the Church and so on. But there was something holy, and good in a human way, about them, in the way they helped each other in poverty, he said.

Pope Francis’ image of the field hospital is apt, he said. It forces one to ask what the priorities are among people whose lives have been shattered, who are hurt and wounded profoundly. Yet at the same time, they have a faith that is “so deep and surprising,” he said.

He recalled a time he and his companions had moved to a new location and had left all their belongings in boxes while they went out to serve in the neighbourhood.

That night they discovered all the boxes had been stolen. They had to use newspapers to cover themselves to stay warm, he said.

The next day Baixinha asked how they liked their new place. Lougen told her they liked it fine, but all their belongings were missing. She told them not to go back to their place until that night.

Upon returning that evening, the Oblates found all their belongings had been restored. They even found their small television set had been replaced by a larger one.

Lougen spent 17 years as a missionary priest in Brazil. In 2010, he was elected the 13th Superior General of the congregation and is now based in Rome.