O’Herlihy didn’t paint a tear, it’s just that some people see one.

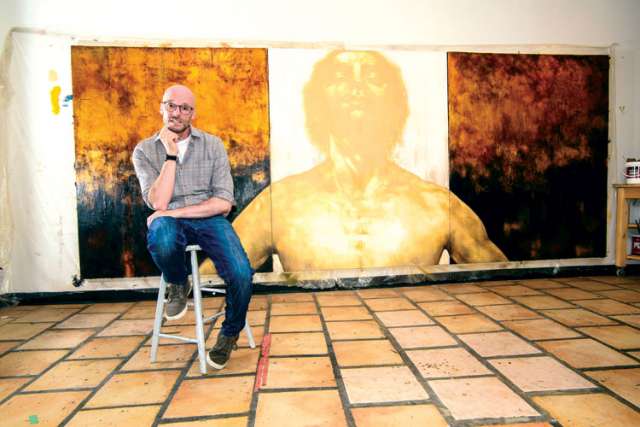

In early October the painting still hung in the studio where O’Herlihy painted it and only a few had seen the completed work, which will hang eventually at King’s University College at Western University in London, Ont. Even before he was finished, one of the other artists sharing the studio space noticed the tear.

“Somebody was standing here saying, ‘I just love the tear.’ And I said, what tear? Where?” recalled O’Herlihy.

The tear is not some miraculous apparition, but rather a product of how the Irish Benedictine monk paints. In preparing his canvas, O’Herlihy likes to spread the gesso or primer fast and thick. He likes a hard, rough surface that hides the canvas. The gesso will then sometimes influence how the paint lies on that surface, or how light reflects off the painting.

Whether you see a tear or not is something of a Rorschach test, said O’Herlihy.

“It’s recognition of yourself as you stand before Christ, that your true identity is revealed to you when you encounter Christ,” he said. “He reflects to you who you are.”

The painting isn’t just a pretty picture. It’s also part of O’Herlihy’s studies for a Master of Theological Studies degree at Toronto’s University of St. Michael’s College. Sent by his abbey for studies, O’Herlihy searched the English-speaking world looking for a program where he could integrate the practice of art with a study of theology.

O’Herlihy wrote to a long list of theological colleges looking for the right program. Some wrote back saying that, though they didn’t have the faculty or other resources for a serious, theological look at art, they hoped he found one because there’s such a clear need for that kind of study.

St. Michael’s was one place where the theological faculty was willing to look beyond the usual path to see different ways of examining theology within culture.

“They have a really cool approach, I think, to learning theology,” he said.

So when O’Herlihy paints, it’s only after deep theological study, prayer and contemplation. The artist hopes there’s more to an encounter with his giant three panel painting than just a possible tear. He wants viewers to come into contact with the incarnate king and with their own humanity.

“It’s through that encounter with Christ that the Trinity is revealed,” he said. “So that made me think that I really wanted to do a triptych. I really wanted to have three parts that relate.”

The grand scale of the painting (the head alone of Christ is nearly a metre from chin to forehead) and the gold leaf on either side of Jesus are enough to encompass the idea of Christ as king and judge of this world. O’Herlihy has steered away from the more conventional symbols of kingship — crowns, sceptres, thrones.

Familiar, well-worn imagery can sometimes get in the way of a fresh, honest encounter with an important religious idea or a work of art, the artist said. Just as Pope Francis has called for a New Evangelization that goes to the margins of society, willing to get dirty and bruised on the street outside the church, O’Herlihy is trying to produce religious art that speaks to people where they are and in new ways.

“Religious imagery for me, when I was young and growing up, was very much like watching westerns on TV,” he said. “The good guys wore white hats and the bad guys wore black hats and you knew exactly where you were.”

As a monk and artist, O’Herlihy’s starting point is always the incarnation. The human is always at the centre of his paintings.

“It’s a deliberate attempt to focus constantly on the incarnation. To make that sense of connection between the word and the flesh,” he said. “That’s the language of the incarnation — that it is in human nature that God is manifest, through each person and their human nature. It’s not apart from it but intrinsic to human nature.”

Christ the King was commissioned for the chapel of King’s University College. King’s chaplain Fr. Michael Bechard hopes to have the painting in place at the chapel just north of the campus on the feast of Christ the King, Nov. 23. Beginning Nov. 3 it will hang in St. Michael’s College’s Muzzo Alumni Hall in Toronto. The Catholic college’s student life committee has organized the display.

O’Herlihy’s serene and tender image of Christ is a long way from the biting lampoons of Irish politicians that began his artistic career.

When O’Herlihy went off to study design at a Dublin art college in the 1990s, he found himself in conflict with fine art conventions and his professors. He loved illustration. His professors didn’t. He loved the immediacy of caricatures. The rest of the college dismissed them as mere play.

But when Ireland went through two elections in a month — Irish coalition governments being somewhat fragile — O’Herlihy found himself in demand. His caricatures were illustrating stories in several daily newspapers and he eventually landed a job at the prestigious Irish Times.

From there he went on to a 10-year career in illustration in the United States. Though he achieved relative success and comfort, he was not at ease or at home. He began to meditate with Buddhists.

“Meditation will bring you back to the faith that you hold that is yours,” O’Herlihy said. “I actually thought, I don’t want to change one set of bells and whistles for another set of bells and smells. I actually want something more profound, something about who I am — the world I live in, and what is important to my sense of being. How can I be who I am? I had been unfaithful to that.”

What followed was a slow re-discovery of his childhood Catholicism and a period in the United States discerning a life as a hermit. The hermitage and its American cultural context weren’t working for the Irishman and he eventually found his way back to Ireland where he has taken solemn vows as a member of Glenstal Abbey.

When O’Herlihy began to paint Christ the King he had a completely different image in mind, and it wasn’t working.

“On day one I started to paint and I thought, God this is crap. It’s just rubbish… dead on the canvas,” he said.

He started again, this time without a clear picture of where he was going.

“You just follow the line. You follow where the paint is taking you,” he said. “The actual process itself becomes an engagement in prayer.”

For the artist and the monk, following the line, discovering what emerges from an encounter with Christ, has been the path of his vocation.