OSHAWA, ONT. - When the doors opened at Msgr. Paul Dwyer High School in early September, it marked 50 years of secondary Catholic education in Oshawa.

The celebrations commenced Sept. 9 at the school in the city east of Toronto, with events scheduled for the duration of the school year. The year-long celebrations are to allow as many of the school’s approximately 8,000 graduates — who include author Randy Boyagoda, former Toronto Argonauts wide receiver Andre Talbot and comedian/actor Justin Landry — to attend.

“We wanted to share this celebration over the course of a year so that if someone is away for something they didn’t miss out,” said Randy Boissoin, chair of the 50th anniversary Committee. “We thought if it was over the course of a year we could generate excitement and build up to May 2013 and hopefully with that excitement work on creating an alumni database.”

Boissoin wants to establish an alumni scholarship fund to assist school graduates who face rising post-secondary tuition costs.

The original high school, run by the Sisters of St. Joseph, operated out of their local elementary school and was named St. Joseph’s Senior School when it opened in 1962. Private at the time, the school offered only Grade 9 and 10 classes in its inaugural year, adding Grade 11 the following September, and Grades 12 and 13 in subsequent years.

“The interesting thing at that point is that the convent for the Sisters was not ready,” said Sr. Conrad Lauber, appointed the school’s principal in 1967, the same year the Oshawa Separate School Board began providing $300 per student in Grades 9 and 10. “At that point the Sisters were driven from Morrow Park (Toronto) out to Oshawa, both the elementary and secondary teachers, and they were picked up again at six o’clock and taken back.”

By the time Lauber became principal — a post she held until 1979 — St. Joseph’s Senior School had relocated and became known as Oshawa Catholic High School (the name change came in 1965). One year later the construction of the convent on the school’s new grounds at 700 Stevenson Rd. N. had been completed, meaning Lauber no longer faced the more than 50-km commute.

The early years were a struggle for the school, as full funding of Catholic education was still years down the road. Unable to compete with the salaries from the public system, Oshawa Catholic High School relied on clergy and dedicated laypeople, who were willing to forego the salaries and benefits offered by the secular school board. This reliance on the latter grew even greater in 1969 when tragedy struck. After an end-of-year staff social, a station wagon with a number of staff in it was involved in an accident. Two Sisters and a lay teacher were killed, and four other Sisters were injured and unable to return to the school. Lauber was the only one able to resume teaching duties.

With few available and qualified clergy, Lauber turned to the laity to fill the positions, putting extra financial stress on the already struggling school.

“At one point when I asked the (Sisters of St. Joseph) for more funding our general superior ... told me that we might not even be able to continue next year because we didn’t have the finances,” said Lauber.

With no additional funding forthcoming, nothing significant at least, Lauber turned to the local community to save the city’s only Catholic high school.

“As we lost Sisters from the staff we had to replace them with laypeople and our costs increased significantly. So to stay alive we ran a walk-a-thon,” said Lauber. “In those days we walked miles not kilometres. The kids walked 25 miles and the parents walked five miles and we raised $56,000.”

Such success turned the walk-a-thon into an annual event which helped cement full-spectrum Catholic education in Oshawa, said Boissoin, who remembers participating in the walk-a-thon as a student from 1974 to 1979.

“When we were forced to do the walk-a-thons and the fundraising activities there was an incredible Oshawa Catholic High School pride within the community ... it also solidified us as a community,” he said. “It was an opportunity for people to show that this is important. When you had a walk-a-thon of that magnitude ... it was almost like a statement.”

It was during this era the Sisters of St. Joseph first sought another name change to honour Paul Dwyer — the spark that lit the school’s flame.

“Msgr. Paul Dwyer was the inspiration behind the founding of the school,” said Lauber. “He’s the one that wanted Catholic education in Oshawa.”

Although approved, Dwyer declined the honour in 1973, telling Lauber over lunch that he felt Dwyer would be too hard for immigrants to spell — something he felt conflicted with his image of welcoming new Canadians with open arms.

“He also said so many other people were involved in the establishment of the school he didn’t want to take all of the credit,” said Lauber, who saw the name change in 1976 to Paul Dwyer Catholic School following Dwyer’s death that year. “Obviously his wishes to not have the school named after him were ignored.”

TORONTO - There’s no denying that Deacon Kevin Brockerville is a communicator.

When he talks about his wife, he smiles wide. When asked how he balances family and his deacon responsibilities, he jokes about having two ropes tied around his neck, eyes lighting up in laughter. And when he describes the people who have helped him throughout his life, his emotion is clear.

And he communicates all of this while being deaf.

Not able to hear since age three, Brockerville credits his faith with moving him forward. And it all started with a teacher in his hometown in Newfoundland.

“She would always take me to the church,” Brockerville said through an interpreter. “I didn’t really understand what church was. I would sit there and see people kneeling and praying but I didn’t know what that was.”

It was this teacher who also made sure Brockerville received the proper education.

“She found where the school for the deaf was that I could go to,” he said.

The school was in Halifax, and moving there for Brockerville was a necessary step in his spiritual journey.

“There I started understanding,” he said. “They taught religion, so I got the idea about my faith. It’s a struggle for the deaf to understand religion but I’m very happy that I had the education that helped me.”

Brockerville moved back to Newfoundland after school, and met a missionary priest from the United States who could sign.

“My mouth was wide open, I was so shocked,” Brockerville said. “‘You mean there’s a priest that can sign?’ It really inspired my wanting to serve. He’s a priest and he’s serving us.”

By the end of the 1960s, then with a wife, Gertrude, who is hearing impaired but not deaf, and his first child, Brockerville moved to Toronto for work and started attending Holy Name Church at Pape and Danforth, where the deaf ministry in Toronto gathered at the time.

“Everyone was signing and the priest was signing,” Brockerville said. “Wow, it was so powerful to me to see that everyone would come.”

The ministry has since moved to St. Stephen’s Chapel in downtown Toronto, where Brockerville serves as a deacon.

“I just felt that God was calling me to serve the deaf people,” he said about his decision to join the diaconate.

But he described his studies — culminating in his ordination in 1984 — as a “real struggle.”

“I was the only deaf person,” Brockerville said. “It was harder (for me) than (for) the hearing people because I had a hard time understanding the language.”

Brockerville explained this is a common thread for all deaf people in grasping theology, and said homilies have to be very simple when signing.

In the end, though, he made his way through the four years of diaconate study.

“I kept listening with my eyes. I kept watching,” he said. “I know that I struggled. But I had to trust God and I trust Him.”

Today, there are four locations for the deaf ministry in the archdiocese of Toronto: in Toronto, Barrie, Oshawa and Mississauga. Brockerville, who spends his time at the downtown Toronto location, is the only deaf deacon, and so has much responsibility, not only with serving at Mass and giving homilies, but also in helping deaf people with further interpretation of the services.

“Some of the deaf have questions about their faith, and if they’re studying something or reading something, I help them,” Brockerville said.

But this man — who said above his responsibilities in the diaconate and in the deaf ministry is his responsibility to his family — is anything but boastful.

“I don’t look for rewards, I look to serve,” he said. “I just follow the faith. I’m here to serve and I serve the best way I can.”

[issuu width=600 height=360 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=120910160538-19846c86f786424e98153821bd480e84 name=diaconate username=catholicregister tag=anniversary unit=px v=2]

TORONTO - For nearly 30 years, George Jurenas patrolled the streets of Toronto, keeping people safe. Today, this retired cop patrols the hallways of hospitals, giving people hope.

Jurenas was ordained a deacon in 2008, and has spent most of his time since as a chaplain at Trillium Health Centre in Mississauga and with the Peel Regional Police. And while he said his main inspiration for entering the diaconate was his own parish deacon, he recognizes his years with the Toronto Police Service showed him he had what it takes.

“People would call me Father Confessor,” Jurenas laughed. “(After I arrested people) they’d be sitting in the back of the cruiser and just seemed to open up to me naturally.”

Meeting so many different kinds of people in his profession, Jurenas said, taught him some valuable lessons.

“Over the years, what I found was people aren’t evil,” he said. “No one wants to live on the streets, no one wants to rob a bank, no one wants to put a needle in their arm. There’s usually a reason why they did what they did. There’s a hurt or a pain or something behind that action that for one reason or another placed them there.”

It’s a lesson that has helped him in many situations, like once when he was faced with a patient who, to put it lightly, did not care for his help.

“I introduced myself, said hi, I’m the chaplain, and I basically get, ‘eff off,’ ” Jurenas said.

“I said hey, no problem, God bless you. But you never know. Someone could be in a real bad place… and it’s not that they don’t ever want to talk to you, it’s just at that time.”

Jurenas never gave up on this man, and eventually they were able to turn a corner. But he’s not always so calm and collected, especially working in the palliative care ward. And it is in showing his true emotions that Jurenas sees the biggest difference between his former job and current work.

“I don’t have to pretend to be tough,” Jurenas said. “I can actually cry with people. There is strength as showing your weakness. As an officer, you (have to) play … tough, and there’s a reason for it. If you act mushy people will walk all over you.

“As an officer you’re always standing behind this façade. I’m tough, I’m in control. Then you realize none of us are really in control.”

This hit close to home for Jurenas when he was diagnosed with prostate and bladder cancer himself before becoming a deacon. He underwent an operation and radiation therapy and is now in remission, but he said the experience gave him insight into what people are feeling and going through in hospitals.

“I’ve laid in that bed,” Jurenas said. “No matter what faith you are, we’re all going through the same fears, the same worries and the same pains when we’re lying in that hospital bed.”

Jurenas uses this kind of non-denominational approach to spirituality in his chaplaincy work.

“For me as a Catholic deacon, it’s really neat when I do go visit people from other faiths, whether it be Muslim, Sikh, Hindu, you name it,” Jurenas said.

“We meet together at a certain spiritual, emotional place. Some people say does it weaken your faith? I always tell them if anything, it strengthens my faith. There’s a face of Christ in all of us.”

Jurenas saw this as particularly true when he experienced what he described as a miracle — a man who was told he had months to live walked out of the hospital a year and a half later. Jurenas and the man’s wife, a Muslim woman, had been praying together every week, he with his rosary, she with her amber beads.

“There’s a sense of respect of each other, even though we’re from different faiths and backgrounds,” Jurenas said. “It just shows you when we concentrate on what we have in common, Christ finds a way.”

Jurenas has also found humour in many situations, such as the time he came across a patient and recognized him as a former biker — one whom he had arrested at least half a dozen times in downtown Toronto.

“I used to tell him, you’re not really good at (being a criminal),” Jurenas laughed. “If (I), this beat cop, can arrest you half a dozen times, you should probably look for another line of work!”

Even former arrestees, Jurenas looked to help.

“Here’s a guy, a big feared biker. When he’d walk down the street people would move out of his way,” Jurenas said. “And all of a sudden he’s like a baby, wearing a diaper, can’t really leave the bed. It really affected him emotionally, that self-esteem drop.”

And so Jurenas went out and bought this man Harley Davidson stickers for his wheelchair.

“It was just beautiful to see, he went from this depressed state to laughing and joking,” Jurenas said. “Last thing I heard he’s at a long-term care facility and he’s scooting around.”

But ever humble, this devoted husband and father of four would never take too much credit.

“I’m basically a mirror, and I just show what you have inside of you,” he said. “At the end of the day you have to realize you’re not a superhero, you’re not a saviour. You’re just a very mortal human being.

“You do what do can.”

[issuu width=600 height=360 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=120910160538-19846c86f786424e98153821bd480e84 name=diaconate username=catholicregister tag=anniversary unit=px v=2]

Early Scripture makes reference to a form of the diaconate

This month marks the 40th anniversary of the arrival of the diaconate in English Canada. But the history of the diaconate actually dates back to the earliest days of the Church.

The first mention of the diaconate comes right out of Scripture, said Deacon Peter Lovrick, director of the formation program for the diaconate at Toronto's St. Augustine's Seminary, who pointed to references from St. Paul in Romans, Corinthians and Timothy in the New Testament.

But the most substantive reference to the diaconate is Acts 6:2-7, which directly refers to St. Stephen as the first deacon:

"And the twelve called together the whole community of the disciples and said, 'It is not right that we should neglect the word of God in order to wait on tables. Therefore, friends, select from among yourselves seven men of good standing, full of the Spirit and of wisdom, whom we may appoint to this task, while we, for our part, will devote ourselves to prayer and to serving the word.'

"What they said pleased the whole community, and they chose Stephen, a man full of faith and the Holy Spirit, together with Philip, Prochorus, Nicanor, Timon, Parmenas and Nicolaus, a proselyte of Antioch.

"They had these men stand before the apostles, who prayed and laid their hands on them."

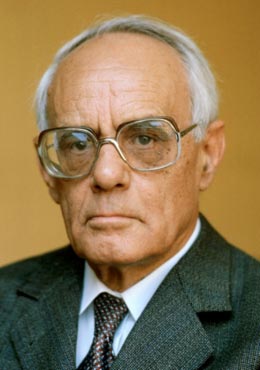

The closing session of the Council of Trent is depicted in an illustration from the 17th century.

- CNS photo/courtesy of Art Resource

Lovrick said some scholars dispute whether these words are specifically pointing towards a diaconate, though Stephen went on to become the first martyr of Christianity, and his name lives on as the patron saint of deacons.

"Many of the early fathers of the Church wrote about deacons," Lovrick said. "Deacons in the early Church had a pretty prominent role, eventually taking upon administrative and juridical positions in the Church.

"They were very closely connected to the bishops… but they were a distinct group. They were not priests."

After several centuries of deacons working closely with bishops, things started to change, said Lovrick.

"They brought in the various orders," he said. "It began to look that the deacon was a step to be a priest, and it became that way."

Today, there is a transitional diaconate, the step immediately before one becomes a priest, and the permanent diaconate, for those who do not go on to the priesthood. But before these were established as distinct ideas, the permanent diaconate began to wane by 1000, and soon disappeared in the western Church.

The Council of Trent, a council of ecclesiastical and theological experts who met in Trent to discuss important matters in the Catholic Church, was the first occasion after the original decline of the diaconate that the idea of a renewal was brought up. In 1563, during the council's 23rd session, came the call for a restoration of the diaconate, a movement that was stirred in the Eastern Catholic Churches, where the permanent diaconate had not been quite as weakened.

"The original proposal that went into the council was very ambitious and spoke a great deal about the separate order," Lovrick said. "But there were other things going on in Europe. Nothing really happened until the 20th century.

"For 500 years, (the restoration) was on hold."

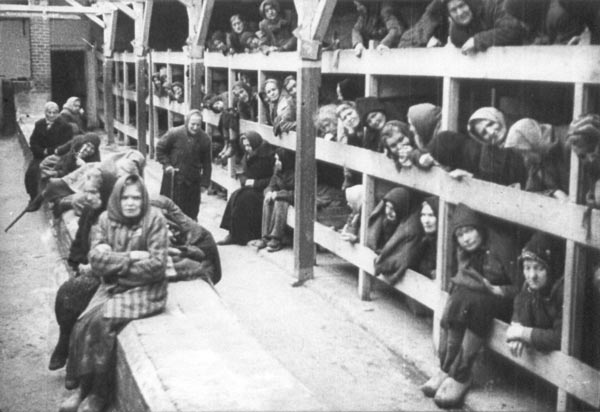

Of all places for the diaconate to begin its revival, it was the Nazi concentration camp Dachau during the Second World War. A small number of Catholic priests were detained there, in a cellblock called the "priest block." And it was there the rumblings of a new diaconate were formulated. Frs. Otto Pies and Wilhelm Schamoni spearheaded the movement.

"They saw Europe crumbling around them," Lovrick said. "They saw the ravages of war, they saw the attack on the Church.

"They had faith that we were going to get through this, but when we got through this, we would be in the ruins and things would need to be rebuilt."

These priests began to write about bringing back the diaconate envisioned at Trent, about how deacons could help the priesthood restore faith after the war. These thoughts were published, and another mind began to write about similar ideas — Fr. Karl Rahner, the great theologian.

"Rahner talked about how there were lots of people in the world doing diaconal things, but they weren't given the sacramental grace of ordination to do it," Lovrick said. "It only made sense to empower people to do what you were asking them to do. That was his basic argument."

The Dachau concentration camp was the unlikely place where talk about the revival of the permanent diaconate evolved. - CNS photo/Reuters

Meanwhile, a charitable movement in Germany called Caritas was getting very involved with restoring the diaconate by publishing articles and hosting open forums for discussion. By 1962, efforts by several groups and individuals came together with a petition for Pope John XXIII, which made its claim:

"Well-known theologians have studied the matter from the historical, theological and practical points of view, and have arrived at the consensus that the proposed restoration (1) is possible, (2) would bear great fruit in the interior life of the Church, and (3) would do much to foster the cause of unity among Christians which Christ so dearly desires."

What followed were seven questions and potential issues of reinstating deacons, and reasons and answers behind all of them; this petition set into motion the events of the Second Vatican Council. Vatican II, much like the Council of Trent, discussed the Church and its place in the modern world. It ran from 1962 to 1965, and the restoration of the diaconate was a solid fixture of discussion.

But the council did something that Trent didn't — it followed through on the diaconate discussion.

"In the (Second) Vatican (Council), 101 propositions were specifically on the diaconate," Lovrick said. "There was a lot of back and forth, some cardinals in support… others against it. But by 1964, the dogmatic document of the Church, Lumen Gentium, (had a) very clear section on the deacons calling for the restoration on the diaconate."

Four years later, in 1968, came the first ordination ceremonies of deacons since the Reformation — fittingly, in Germany. Several other countries, including Colombia, followed suit, so that by 1970 there were almost 100 permanent deacons around the world.

The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops met in Winnipeg in 1968 and voted overwhelmingly to ask Rome for permission to restore the diaconate in Canada. By 1969 it was granted.

Toronto came aboard in 1972, thus forming the first class of permanent deacons in the archdiocese of Toronto, who were ordained two years later. To date, 272 men have been ordained deacons in Toronto.

[issuu width=600 height=360 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=120910160538-19846c86f786424e98153821bd480e84 name=diaconate username=catholicregister tag=anniversary unit=px v=2]

When asked just what exactly is a deacon, Steve Pitre bursts out laughing.

“You’ve asked the question that theologians have been pondering for 50 years, and they still haven’t come up with a definitive answer,” said the co-ordinator of the permanent diaconate for the archdiocese of Toronto.

That’s because the nature of the deacon’s work is so all-encompassing and thoroughly engaged with his community that it can often be difficult to lay a strict definition to their ministry.

“The deacon is to be the icon of Christ the servant. When we talk about service, it’s in three areas: charity, liturgy and the word,” said Pitre.

Diaconate candidates in Toronto do four years of formative study and practice at St. Augustine’s Seminary. Unlike a priest, the deacon is ordained through a call to service. The ministry is open to all men between the ages of 35-59, both single and married, and, if married, requires the complete consent and support of his spouse (wives are active in their husband’s ministry).

“If he’s married, the call comes from his marriage and therefore from his family. But, in essence too, even if he’s single, it’s still coming from the family, from his support and from his friends,” said Pitre.

“While everybody seems to see us strictly in liturgy and preaching, that really comes from our service of charity. It starts with our families first, the community and then with a special emphasis on the less fortunate, the weaker members and the marginalized of our society,” said Pitre.

Indeed, in St. Ignatius’ letter to the Trallians, he notes: “… as ministers of the mysteries of Jesus Christ, the deacons should please all in every way they can; for they are not merely ministers of food and drink, but the servants of the Church of God.”

In this way, the deacon serves as a vital part of our Christian community. They work not only in parishes, but in all places where there may be need such as hospitals, prisons, even on the streets. They are the mission of service personified, bringing the liturgy of our faith and the essence of charity to all in our communities who may be at need.

[issuu width=600 height=360 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=120910160538-19846c86f786424e98153821bd480e84 name=diaconate username=catholicregister tag=anniversary unit=px v=2]

TORONTO - When the first class for the permanent diaconate gathered for its initial orientation Sept. 16, 1972, the candidates brought along their wives and children. For those present that day, it was the beginning of many bonds that would last for years.

“I made real life-long friendships with them,” said Alexander MacGregor, one of the 33 men who met that day. “Meeting other men and their wives and their families who were dedicated, inspiring, hard workers — it was really inspiring to be involved.”

Forty years ago this month, the permanent diaconate came to English Canada with the launch of a deacons’ program in the archdiocese of Toronto. That followed the launch of similar programs in the United States, Europe and other countries. The ministry of deacons, which had been important in the early Church, was revived at Vatican II to assist in parish work and to proclaim the Gospel in the community, particularly through acts of charity.

From the first class of 33 candidates, the diaconate has spread across Canada so that today deacons are commonplace in most dioceses. Toronto alone has more than 100 active deacons and has ordained 272 deacons since 1972. Many will officially celebrate the 40th anniversary on Sept. 29 at a Mass celebrated by Bishop Vincent Nguyen, followed by a gala dinner.

Stanley MacLellan, who worked in the financial industry and had always been active in his parish, heard about the diaconate through his university pal, Fr. Paul Giroux, a member of the archdiocese of Toronto’s committee on the permanent diaconate.

“He came to my parish and we renewed our friendship,” MacLellan said. “He told me what they were trying to do. I thought it sounded interesting.”

Appointed co-ordinator of his year, MacLellan helped shape that inaugural class.

“That was an interesting two years to start, creating the program as we went along,” he said. “We got together so many times over the next two years, planning the next session in the seminary, changing as things went along.”

When the first class of deacons began its two-year course in 1972, the candidates had no idea what to expect.

“It was unusual because while we were going through the class, they were also discovering what was needed,” said MacGregor. “In retrospect, the first class got through easier than the other classes. I think from the experience of the first class, those who were in charge refined both the entrance requirements and what was being taught.”

Yes they did, but prior to 1972, the committee on the permanent diaconate in Toronto had to decide who could enter the program, how the program would run and the role of deacons within a parish.

Two members of that committee, Giroux and Msgr. John O’Mara, had attended a conference in Chicago on the permanent diaconate in 1970, bringing back two main ideas about the ideal candidate: first, they had to be more than just a volunteer, they had to be an “ambrosian model”; second, their wives must be like-minded and taken into consideration. To this day, there is a tradition of deacon wives who are just as involved as their husbands.

And just as the ideal candidate was formed, so was the structure of the program, a two-year journey that was very academic in nature. It included 10 weekend sessions, including a Sunday evening potluck with wives and children. Giroux, who became the first director of the program, made sure that family and work remained a priority to all candidates.

For MacGregor, family had to remain a priority. After all, he had 10 children.

“I was involved in several projects — school board, figure skating — and I thought I could do something different in a different field,” he said.

But keeping family a priority wasn’t the only prerequisite to be considered a good candidate for deacon. Candidates had to be over 35, in good health and mentally, emotionally and financially stable, with a good job.

As a result, the first class formed at St. Augustine’s with 33 men, 28 from the archdiocese of Toronto, and included men in their 30s, 40s and 50s, all with different backgrounds. There was a retired naval officer, an assistant superintendent of a school board, a lawyer, an insurance broker. All but two were married, and so those two took a vow of celibacy, as required for unmarried or widowed deacons.

Then-Archbishop Philip Pocock said at the time that he felt grateful to all the men in the class who felt called to serve, for different reasons, from different places in life.

Over the years, there have been many changes to the program. The academic portion is now four years long, with a class graduating every two years. More recently, a foundation year for men to decide if this is the right path for them was added in conjunction with a similar year for seminarians.

MacGregor is happy to have been a part when it was all just beginning.

“Coming up with clear direction as to what ministries were and how the formation program should work was always a challenge, but it gave lots of excitement (to my) life.”

Only a handful of deacons from that first class are still alive, including two, Tom Cresswell and Larry Rogers, who later became priests after their wives died.

But the legacy of the first class lives on, both in the basic structure of the program and in the hearts of its participants.

[issuu width=600 height=360 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=120910160538-19846c86f786424e98153821bd480e84 name=diaconate username=catholicregister tag=anniversary unit=px v=2]

Through the ups and downs, couples persevere in marriage

By Tony Gosgnach, Catholic Register SpecialHAMILTON, ONT. - What is the secret to a long and happy marriage? Communication and being able to understand each other’s point of view, say Eugene and Regina Jasin. They should know — the couple, natives of Lithuania, are celebrating their 70th wedding anniversary this year.

They were among 475 couples recognized by the diocese of Hamilton for celebrating 25, 40, 50 and 60 or more years of married life in 2012 during the annual Wedding Anniversary Mass at the Cathedral of Christ the King on Sept. 9. The Mass was celebrated by Hamilton Bishop Douglas Crosby.

The Jasins said although seven decades have passed, they cannot remember one time when they had a serious argument. This is despite the fact they have experienced some terrible stresses, such as fleeing for Germany on horseback with their infant daughter in the face of the communist takeover of their land during the Second World War.

“The main thing you have to understand is the other person, because it’s not exactly the same as what you’re thinking,” said Eugene. “The other person has different thoughts, so you have to accept what someone else thinks and talk it over.”

Ron and Mary Smithson were at the Mass having celebrated their 61st wedding anniversary just the day before. They have been imparting their wisdom about married life to couples for well over two decades as founding members of the marriage preparation course in their parish of St. Francis Xavier in Stoney Creek, Ont.

“We were busy all our lives and didn’t have a lot of material wealth, but we had a lot of love and a lot of family,” said Mary.

“We always worked together raising the family; it wasn’t just her job or my job,” added Ron. “It was our job and that’s the way we looked at life all the way. We’ve had some good times and bad times, but we get through them all. One of the blessings is we were married on Sept. 8 … that’s Our Lady’s birthday and that’s someone who has been in our life all along.”

The Smithsons point to compromise, openness, honesty and not emphasizing material goods as key aspects to a successful marriage.

“Marriage is about compromise. What you were before you were married and what you are after is going to change. But both of you change,” said Ron.

During his homily, Crosby said the couples in the church served as a testament and witness to God’s goodness and love.

“Today is a day of celebration, a celebration of enduring love and fulfilled commitment,” he said. “It is both a reminder and a renewal of the promises made on the day you married many years ago.”

He added that each couple present was a living reminder of God’s love and its permanence. “Your marriages tell all of us, but especially young people, that lasting love is possible,” he said.

Crosby spent some two hours in the parish hall after the Mass, meeting each of the couples and posing for photos with them.

Teresa Hartnett, director of the diocese’s Family Ministry Office, said the Wedding Anniversary Mass has been held annually for some three decades and is a reflection of the Church’s desire to honour a foundational vocational aspect of the Catholic faith.

“It’s just continued to grow and grow every year,” she said, adding the event is also a part of the diocese’s overall commitment to strengthening family life, in addition to the Retrouvaille program for troubled marriages, Marriage Encounter weekends, marriage enrichment evenings and referrals for counselling.

(Gosgnach is a freelance writer in Hamilton, Ont.)

For the second time, the provincial government has taken over one of the province's Catholic school boards.

The Windsor-Essex Catholic School Board is the latest to fall under provincial control after an external review found board staff was willing to risk a strike to balance its budget. The board's budget was short $2.2 million this year, the fifth time in the past six years it had failed to balance its books. Staff noted that a strike might help to find those savings.

The board had no contingency plan to find the savings, said Deloitte, the consultants who authored the review.

Norbert Hartmann, who oversaw the Toronto Catholic District School Board when the province took it over in 2008, has been appointed to oversee the Windsor board's financial management and administration.

Barbara Holland, chair of the Windsor board, had predicted a takeover was coming in early August. She told The Catholic Register's Evan Boudreau that it wasn't so much financial instability, but more of a retaliatory measure for the board filing for conciliation to resolve the collective bargaining difficulties it was having with its teachers (before the province introduced its Putting Students First legislation Aug. 27).

"I do feel that it is a retaliatory measure and it is retaliation because we spoke out on this issue," said Holland.

Catholic trustees bound to earlier deal, not new legislation

By Evan Boudreau, The Catholic RegisterTORONTO - The devil is in the details as far as Catholic school boards are concerned when it comes to side-stepping strikes and lockouts.

The Putting Students First Act, the Liberal government’s legislation to freeze teacher salaries, will require Catholic schools to operate by a different, more restrictive, set of rules than the province’s public boards. And that has the Ontario Catholic School Trustees’ Association (OCSTA) up in arms.

Catholic boards will continue to be bound by the deal struck in July between the Ontario English Catholic Teachers’ Association (OECTA) and the Ministry of Education, even though the government legislation has backtracked on some key provisions contained in that agreement.

To get the Conservatives on side with Putting Students First, Dalton McGuinty’s Liberals had to remove controversial clauses that would have stripped school boards of some rights related to the hiring of permanent teachers and managerial oversight of diagnostic testing. Public boards will now be able to negotiate locally with teachers on those contentious issues, while the trustees from Ontario’s 29 Catholic boards are stuck with the deal the government negotiated with OECTA.

“The effect of these changes are in fact no change at all,” said Bob Murray, the OCSTA’s director of legislative and political affairs. “It’s subverting the role of trustees.”

The OECTA deal leaves virtually no room for local collective bargaining because all the substantive issues were settled without input from the province’s trustees.

“Under the proposed legislation no local collective bargaining will happen,” Murray said. “It’s an agreement that local trustees never agreed to.”

On July 4, following six months of unsuccessful bargaining, the Catholic trustees walked away from the table. That left the government and OECTA to strike a deal that imposed a two-year wage freeze, a reduction in sick days from 20 to 10, and elimination of the right to bank sick days until retirement. But the deal also gave the union greater input in hiring permanent teachers and some control over diagnostic testing.

“We said from the beginning that Ontario has a problem fiscally and something had to be done and we were willing to help out,” said Marino Gazzola, president of OCSTA.

“I think our concerns are the same now as they were before any proposed changes.”

He said that in negotiations with the government, OCSTA has consistently opposed ceding rights to the union on the issues of hiring and diagnostic testing. He said it’s not for him to say if the Liberals finally changed their position due to pressure from the Conservatives.

“If I had the answer to that I would probably be a millionaire,” he said. “We’ve been voicing these concerns all along and we’ve been firm in our position and we’ve been strong and consistent in our position.”

Those concerns were that provisions surrounding the hiring practices and diagnostic testing removed managerial rights and significant checks and balances from the boards. Under the changes, the trustees believe hiring now gives seniority greater weight than overall qualification, while granting teachers control of diagnostic testing gives them the ability to hide under-performing students.

“All students in Ontario should be able to receive an education from the most qualified teachers and benefit from the insight gained from the use of system-wide diagnostic tests that include parents,” said Gazzola. “School boards in this province have serious concerns about the proposed legislation.”

OCSTA was surprised to learn that the amendments to Putting Students First would not apply to the Catholic boards. They are now calling for additional revisions to essentially veto the controversial areas of the OECTA agreement so that Catholic boards have the same ability as public boards to negotiate locally with teacher unions.

“This legislation will create inequity in our system,” said Gazzola. “We urgently call on your government to amend the legislation to honestly reflect the changes proposed by the opposition.”

More...

TORONTO - Ontario’s Student Advisory Council, which brings together students from all over Ontario, is lively, full of discussion and debate.

The council, a yearly initiative created in 2009 by the Ministry of Education, consists of 60 students in all sectors of the education system, including Catholic boards. The students participate in discussions, team-building and leadership activities, as well as identify issues within their schools and offer suggestions for positive change.

Gary Wheeler, senior media relations co-ordinator at the Ministry of Education, said the purpose of the council is for members to share their ideas and advice with the Minister of Education on how to ensure Ontario’s schools remain “the best in the world.”

“The council is about empowering you to ‘be the change,’ ” Wheeler said in an e-mail. “It is an opportunity to think big, SpeakUp (programs to engage students academically and socially) and take action to help other students across the province.”

Ben O’Neil, now a Grade 10 student from the Ottawa Carleton Catholic School Board, says he didn’t necessarily find Catholic students were equally represented on the council, but that it didn’t really matter.

“It was students from every board, every different place from Barrie to London, North Bay, Ottawa, Thunder Bay, Toronto,” O’Neil said. “It shows you that no matter what school it is, Catholic, public … we are all students, we are all equals.”

O’Neil applied to be on the council for the one-year term through the encouragement of a friend. The council met for the first time in May of this year, and met again in August before the school year begins after Labour Day.

O’Neil says meeting with different students from all over the province was an eye-opening experience.

“It’s interesting to see that there are those similarities, those basics,” O’Neil explains. “Every school has bullying. We have more faith-based groups, but it’s interesting to share ideas.”

For Alicia Pinelli, a graduating student who represented the Niagara board, being on the council has been an “amazing experience.”

“It seemed that the Catholic students all kind of gravitated (to talk about) things that weren’t common in our schools, weren’t open in our schools,” Pinelli said. “The public schools are more open to a lot of different things. It was a good experience to see how the two interacted, how the two could change each other.”

But not everyone thought all the discussions were particularly productive.

Enrique Olivo, an incoming Grade 11 student from the Toronto Catholic District School Board, felt a bit of a backlash towards Catholic schools, especially when discussing the issue of Gay-Straight Alliances.

“(No one wanted) to say anything controversial,” Olivo said. “At times you could feel the tension.”

Still, Olivo, who will also act as treasurer of his school’s student council this year, thinks the advisory council does good work.

“We covered a whole bunch of issues: dealing with mental health problems and how schools should focus on that, technology in the school, a little bit about equality amongst races, sexual orientation.

“The council will definitely make a lot of changes.”

Basilian curriculum focuses on the Catholic in Catholic education

By Evan Boudreau, The Catholic RegisterTORONTO - The Basilian Fathers are working on a professional development curriculum for teachers that will focus on the distinctiveness of Catholic education.

“We are moving from being the teacher of the students to the teacher of the teachers,” said Fr. George Smith, C.S.B., who pitched the new curriculum at a Basilian conference held last March. “It’s easier for us to be the teachers of the teachers because there are fewer of them (than students).”

Using contemporary adult eduction techniques, which Smith described as “animation and facilitation,” the course aims to re-evangelize teachers, including those in administrative positions.

“We want to bring teachers together to explain what they do. Hear what is distinct about the school that we teach in,” said Smith. “It’s about empowering teachers to stand up and say ‘I’m a teacher in a Catholic school and here is why.’ ”

Expected to be ready for the fall of 2013, the curriculum will first appear in North America’s three Basilian-owned high schools: Toronto’s St. Michael’s College School, St. Thomas High School in Texas and Catholic Central High School in Detroit.

The curriculum will be explained to staff by two Basilian Fathers who will facilitate the program. They will be among 10 to be selected for the role during a Basilian conference in Houston in December.

During the professional development days, the Basilian facilitators will offer their opinion of what a Catholic education should be. The aim is to have teachers re-energized about their faith, which Smith said has become “lukewarm” for most.

In the paper he presented in January, Smith blamed advances in social communications, scientific and technical research, problems of globalization, new and emerging political, economic and religious forces and secularization for weakening the faith among teachers. By reigniting the teachers’ faith, Smith hopes to see a trickle-down effect throughout schools.

“I really see this as a wonderful example of the New Evangelization,” said Smith. “We’re trying to create an environment where children feel as if they’re in a community of faith.”

Although only Basilian schools will be offered this service at first, the intention is to make it available to publicly funded Catholic schools in the long run.

“When I look five years down the road I would like to see this (curriculum introduced) into areas with socio-economic challenges,” said Smith, calling this a preservation of the Basilian roots of educating the impoverished.

But this is about more than preserving Basilian ideologies, said Smith, referring to the “educational emergency” of a Catholic school system that is growing weaker in the faith, a topic Pope Benedict XVI has often discussed.

“We are convinced that if our teachers don’t know why Catholic education is distinctive, then Catholic education will disappear in this country within a generation,” said Smith, adding that it’s the Catholic system’s attention to values which sets it apart.

School, parish, family come together to form a Catholic community

By John B. Kostoff, Catholic Register SpecialCatholic schools exist to assist committed families and their parishes celebrate and live their faith in our communities. But people sometimes say this triad of school, church and family is no longer functional. Yes, it can be challenging to keep all the partners working in harmony, but it is a challenge we must never abandon because the result of failure is a weakening of our faith community.

When examining the early Church and how Jesus lived with His disciples we find six consistent elements of their life together. They were welcoming, celebrating, learning, reconciling, serving and praying with each other and the larger community. We must seek the same things in our parish-school relationships.

There are many teachers, parents and priests working to make this relationship more meaningful. It is a task the entire Catholic community must embrace if it is to achieve continuous improvement of our schools. At Vatican II, the Church shifted its emphasis from institution to community. Its Declaration on Education said a “Catholic school is distinguished by an attempt to build community, permeated by the Gospel spirit of freedom and love.” But this concept of community should never be truncated to just the local school. It must include the larger concept of community, embracing the parish, the school and the family. We cannot think of our Catholic community without recognizing that a community only exists if it includes all three of these pillars.

Building this community requires hard work and common sense. First, it obligates us to see the importance of this relationship and strive to make it work. It means abandoning traditional ways of doing things and not imposing our will on others (“thy will be done,” not my will be done.)

Second, let’s recognize our strength when we work together, acknowledging each other’s importance but not exclusive right. It is precisely because we form a partnership that we should be freed from the egoism and self-centred and controlling ways that often mark the secular world.

Finally, we need to seek opportunities to illustrate this partnership to students, teachers and parishioners. Our community must see the concrete ways this relationship can be made viable and enriching for all. We become stronger as a Catholic community when we give words to what we profess. But we must be mindful that this relationship is often fractured when adult concerns are imposed on our schools and when we ignore the unique role filled by Catholic schools.

The need for parish, school and home to work together has never been greater. Below are suggestions to help achieve that goal:

-

o At registration, principals should invite the parish priest to help greet new parents. There should be a letter of welcome from the pastor as well as the principal, and recognition that registration is an opportunity to demonstrate to parents the importance of co-operation between parish, school and home.

-

o Meetings are a reality of modern life so make them productive. The local priest should be invited to address the faculty at one of their first meetings and the principal should be invited to speak to the Knights of Columbus, Catholic Women’s League or the parish council. Principals and pastors should meet quarterly, possibly over lunch or breakfast.

-

o Schools should be unwavering advocates for the parish and likewise the parish for its Catholic schools.

-

o While there may be issues of a larger nature confronting the school system or Church, work at improving one parish and one school at a time.

-

o Building relationships is essential, so even in large parishes one priest should be designated as the contact for each school and, likewise, the principal should be the main contact with the parish, not a chaplain, other school administrator or teacher.

-

o The parish bulletin should provide space each month for information about what is occurring in schools from a religious perspective, and the school newsletter should provide space for the pastor to provide information about the liturgical cycle, upcoming feast days, prayers, etc.

-

o Schools and parishes should work together on holding missions or retreat days that can include a talk by the local priest, student involvement and community prayer and fellowship.

-

o Create a pastoral plan in September that outlines events that the parish and school will do jointly and publish the calendar in the parish and school bulletins.

-

o Parishes should provide a bulletin board for schools to show off student achievements and share school news, and schools should do likewise for parishes to promote church events.

-

o All school newsletters should contain the parish Masses and organizations and all parish bulletins should contain school information.

-

o In the event of significant curriculum changes, school officials should discuss them with the priest, just as the priest should discuss with principals any new approaches to the celebration of the sacraments.

-

o Link parish youth ministers with the local school and work together on events and ministry.

-

o Priests should regularly proclaim from the pulpit the value of Catholic education, and become regular visitors to secondary schools. The local priest should not be a stranger to the community.

-

o School councils should have a parish rep to facilitate two-way communication, keeping the pastor informed on school matters and the school informed on parish issues.

-

o Vocation days or vocation weeks should be a hallmark of our schools. Schools should have a vocation plan beginning in elementary school that stresses lay vocations and the vocation to religious life.

-

o Schools should encourage faculty after-school retreats as a way for staff to link to the local parish and engage in prayer, socializing and sharing a common mission.

-

o Schools should consider holding drop-in Fridays, where a parish priest can drop by as school is dismissing to talk to staff. No agenda, just coffee, treats and dialogue between the staff and the priest.

-

o Involve the local school trustees by inviting them to meet with the Knights of Columbus and Catholic Women’s League, address the parish after Mass or speak at schools on an information night.

-

o The pastor and the principal should be on each other’s speed dial.

People looking for perfection in our Catholic homes, schools and churches will be horribly disappointed. They all are populated with struggling people. So make a list of complaints if you must, but then tear it up, because there is already too much to do and so much at stake.

(John B. Kostoff is the Director of Education for the Dufferin-Peel Catholic District School Board and the author of Auditing Our Schools.)

World Youth Day 2002 - Six days in July that transformed Toronto

By Michael Swan, The Catholic RegisterSomewhere in Toronto today there’s a 10-year-old kid who got a second lease on life at World Youth Day 2002. Dr. Katherine Rouleau remembers that premature baby with all the awe and confusion doctors regularly bring to miracles.

“We had a baby who was quite sick. Actually, it was a newborn of a couple who were so grateful that their premature child had survived that they showed up at Downsview at the crack of dawn in the sweltering heat,” recalled Rouleau.

Rouleau was medical director of World Youth Day 2002. On July 28 a decade ago she had 800,000 potential patients corralled into an open field at the north end of Toronto. Many of them had endured a night of cold and rain, praying the Divine Office and singing through the night. Under the morning sun, people continued streaming in. And then it was raining again as Pope John Paul II arrived to celebrate Mass with them.