He was Pope for not quite five years (1958-63), but made a lasting impact due to Vatican II and important encyclicals, but also due to his warmth, cheerfulness, holiness and sense of humour. He had a wisecracking, tongue-in-cheek, self-deprecating side to his character that won him international admirers, among both Catholics and non-Catholics, and made him known as the Good Pope.

Visiting a hospital he once asked a boy what he wanted to be when he grew up. The boy said either a policeman or a pope. “I would go in for the police if I were you,” the Holy Father said. “Anyone can become a pope — look at me!”

Another time, in reply to a reporter who asked, “How many people work in the Vatican?” he said: “About half of them.”

On his simple upbringing, he wrote, “There are three ways to face ruin: women, gambling and farming. My father chose the most boring one.”

But John XXIII was a serious thinker and writer, particularly when it came to social justice issues. He produced eight encyclicals, including two that are historic, Mater et Magistra on Christian social doctrine and his landmark treatise Pacem in Terris.

Issued in 1963 at the height of the Cold War, Pacem in Terris was one of the most important papal encyclicals of the 20th century. Pope John, dying of cancer at the time, urged the world to move beyond a Cold War mentality and forge lasting peace and promote the common good through the creation of societies based on truth, charity, justice and human rights. He called for an end to the arms race and a ban on nuclear weapons.

The encyclical found an international audience. It was praised at the United Nations, published by both the Soviet news agency Tass and by The New York Times, and Pope John was lauded by the Washington Post as “the conscience of the world.” Time magazine named him Man of the Year.

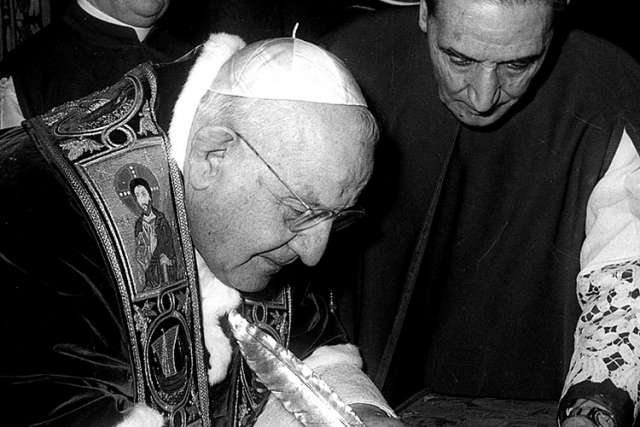

With his humility, gentleness and active courage, John XXII constantly reached out to the marginalized, visiting the imprisoned and the sick and welcoming people from every nation and faith. He visited many parishes in Rome, especially in the city’s growing suburbs. His contact with the people and his open display of personal warmth, sensitivity and fatherly kindness earned him the nickname the Good Pope.

He was also committed to the cause of Christian unity. As a Vatican diplomat his work in Bulgaria and Turkey put the future Pope in close contact with many Christians who were not in full communion with the Catholic Church. This inspired him as Pope to try to rebuild the unified Church that had been lost over the centuries. In 1960 he created the Vatican’s office for promoting Christian unity.

Although he served as Pope for less than five years, Blessed John XXIII left one of the most lasting legacies in the Catholic Church’s history by convening the Second Vatican Council. He called the council in 1962 for two main reasons: to help the Church confront the rapid changes and mounting challenges unfolding in the world, but also to push the Church towards Christian unity.

Convoking the council launched an extensive renewal of the Church. It set in motion major reforms in Church structure, affecting the liturgy, ecumenism, social communication and Eastern churches, that still resonate today. John XXIII understood the world was on the cusp of dramatic change. He had witnessed the dark forces of war and understood the issues that stood in the way of lasting peace. He had witnessed the dismantling of colonialism and the rise of the Cold War, and he foresaw the coming of a global technological revolution unlike anything since the Industrial Revolution.

Barely three months into his papacy, John XXIII, declaring it was time to open the windows and let in some fresh air, decided to convene Vatican II. A surprised Vatican official told him it would be impossible to open the council in 1963. “Fine, we’ll open it in 1962,” he replied. And he did.

John also established the Pontifical Commission for the Revision of the Code of Canon Law, which oversaw the updating of the general law of the Church after the Second Vatican Council, culminating in publication of the new code in 1983.

There was nothing in John’s simple upbringing to indicate a life of greatness. Born in Sotto il Monte, Italy, in 1881, Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli was one of 13 children in a family of sharecroppers. He entered the minor seminary at the age of 12 and was sent to Rome to study at the age of 19.

He was ordained to the priesthood in 1904 and, after several years as secretary to the bishop of Bergamo (interrupted in 1915 when he received a first-hand look at the horror of war as a stretcher-bearer and chaplain in the First World War), he was called to the Vatican. In 1925 he began serving as a Vatican diplomat, first posted to Bulgaria, then to Greece and Turkey and, finally, to France in 1944, where he became the Holy See’s first permanent observer at UNESCO. He was named a cardinal and patriarch of Venice in 1953.

After more than five years as patriarch of Venice, then-Cardinal Roncalli was elected Pope on Oct. 28, 1958 after 11 ballots. At age 76 he was expected to be a transitional Pope. As a cardinal, he had not been part of the Vatican power structure but instead had earned a reputation of being a bridge builder and someone who would connect with cardinals and lay Catholics. No one foresaw the possibility that an idea would come to him “like a flash of light” and he would call a Vatican council that would initiate one of greatest eras of renewal in Church history.

Pope John later deadpanned that the first cardinals he informed about his grand plan reacted with “a devout and impressive silence.” Other cardinals reacted with what was described as “bewilderment and worry.” The council, however, energized the faithful as it produced 16 documents that to this day are a foundation of the life of the Church