Adaptability has been the name of the game for most schools forced to lean on the creativity and tech savvy of teaching staff in a way that is unprecedented for even today’s computer-literate generation.

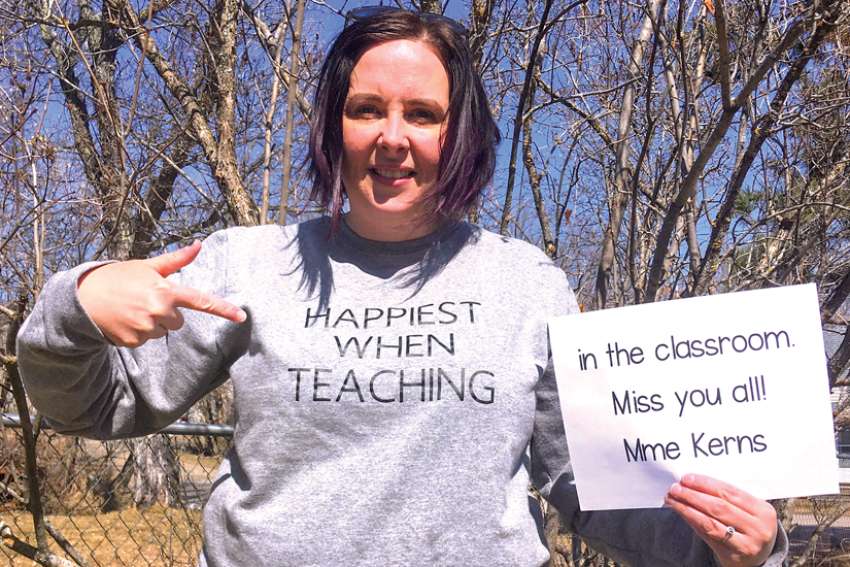

For teachers like Kat Kerns of École Sté-Marguerite Bourgeoys in Kenora, the traditional classroom education has been replaced with online simulations through the use of multiple platforms.

“Everyone, both teachers and students, were somewhat thrown into the unknown,” said Kerns, who teaches Grade 1 and 2 French immersion. “Routines quickly changed and consistency was gone. My hope was to create something that was somewhat familiar to what we were doing in the classroom.”

A large part of Kerns’ curriculum consists of a creative take on the game BINGO, which is suited for students with varying levels of online access.

“At school we use BINGO templates during our literacy period, so I decided to replicate this into versions for our online learning,” said Kerns. “Students are only asked to participate where interested and (it) meets their family’s needs at this time.”

Part of the game-board template includes the option to go on a virtual field trip where students watched a live-stream of nesting eagles in Decorah, Iowa.

“We were lucky that during this week, one of the eaglets hatched,” said Kerns. “Many families were able to watch this happen live. Those who were not, I was able to save the clip and share with them.

“Exploring the life cycle of an animal is part of our science curriculum. If we had been in the classroom, we would have been watching it together, but we were still able to be together in a sense using our digital field trip.”

Christine Motran teaches secondary students age 16 to 21 at Monsignor Fraser College Norfinch Campus in Toronto, an alternative high school where she says many pupils require extra academic and social support, which has posed an extra hurdle to virtual learning.

“Distance learning has made providing support difficult as the signs for help are less obvious and some students will not reach out unless prompted,” said Motran. “I recently experienced this with students and had to reach out through various forms of communication to assess which accommodations might provide the best support for them.”

The issue of equitable online access has been a major challenge, particularly at the high school level. By the end of April, the Sudbury Catholic District School Board will have deployed approximately 900 laptops and iPads to students in need across their district. School boards throughout the province continue to work with families to ensure access to online learning, which includes finding creative ways to accommodate needs.

“Each of my students’ circumstances at home is different,” said Motran, who works at the Toronto Catholic District School Board. “Lack of access to the Internet means some are not able to engage in Google classroom, which we have been using. Support is on the way to remedy the access to technology.”

Meantime, Motran has sent pen-and-paper assignments to students and followed up over the phone.

“Sometimes even this has revealed challenges as students might not have their own phone or are not available to communicate during office hours,” she said.

Despite these challenges, teachers say that staff and students have shown innovation, resilience and good faith while working through distance learning.

“Even though we can’t physically be in our classroom right now, the online learning environment has helped bring some normalcy back into students’ lives,” said Susan Nigro-Perrotta, high school English teacher and department head at St. Basil-the-Great College School in Toronto.

“I truly believe the skills students have developed during this time will positively impact their learning and achievement when we return to the face-to-face environment.”