Features

OSHAWA, ONT. - When the doors opened at Msgr. Paul Dwyer High School in early September, it marked 50 years of secondary Catholic education in Oshawa.

The celebrations commenced Sept. 9 at the school in the city east of Toronto, with events scheduled for the duration of the school year. The year-long celebrations are to allow as many of the school’s approximately 8,000 graduates — who include author Randy Boyagoda, former Toronto Argonauts wide receiver Andre Talbot and comedian/actor Justin Landry — to attend.

“We wanted to share this celebration over the course of a year so that if someone is away for something they didn’t miss out,” said Randy Boissoin, chair of the 50th anniversary Committee. “We thought if it was over the course of a year we could generate excitement and build up to May 2013 and hopefully with that excitement work on creating an alumni database.”

Boissoin wants to establish an alumni scholarship fund to assist school graduates who face rising post-secondary tuition costs.

The original high school, run by the Sisters of St. Joseph, operated out of their local elementary school and was named St. Joseph’s Senior School when it opened in 1962. Private at the time, the school offered only Grade 9 and 10 classes in its inaugural year, adding Grade 11 the following September, and Grades 12 and 13 in subsequent years.

“The interesting thing at that point is that the convent for the Sisters was not ready,” said Sr. Conrad Lauber, appointed the school’s principal in 1967, the same year the Oshawa Separate School Board began providing $300 per student in Grades 9 and 10. “At that point the Sisters were driven from Morrow Park (Toronto) out to Oshawa, both the elementary and secondary teachers, and they were picked up again at six o’clock and taken back.”

By the time Lauber became principal — a post she held until 1979 — St. Joseph’s Senior School had relocated and became known as Oshawa Catholic High School (the name change came in 1965). One year later the construction of the convent on the school’s new grounds at 700 Stevenson Rd. N. had been completed, meaning Lauber no longer faced the more than 50-km commute.

The early years were a struggle for the school, as full funding of Catholic education was still years down the road. Unable to compete with the salaries from the public system, Oshawa Catholic High School relied on clergy and dedicated laypeople, who were willing to forego the salaries and benefits offered by the secular school board. This reliance on the latter grew even greater in 1969 when tragedy struck. After an end-of-year staff social, a station wagon with a number of staff in it was involved in an accident. Two Sisters and a lay teacher were killed, and four other Sisters were injured and unable to return to the school. Lauber was the only one able to resume teaching duties.

With few available and qualified clergy, Lauber turned to the laity to fill the positions, putting extra financial stress on the already struggling school.

“At one point when I asked the (Sisters of St. Joseph) for more funding our general superior ... told me that we might not even be able to continue next year because we didn’t have the finances,” said Lauber.

With no additional funding forthcoming, nothing significant at least, Lauber turned to the local community to save the city’s only Catholic high school.

“As we lost Sisters from the staff we had to replace them with laypeople and our costs increased significantly. So to stay alive we ran a walk-a-thon,” said Lauber. “In those days we walked miles not kilometres. The kids walked 25 miles and the parents walked five miles and we raised $56,000.”

Such success turned the walk-a-thon into an annual event which helped cement full-spectrum Catholic education in Oshawa, said Boissoin, who remembers participating in the walk-a-thon as a student from 1974 to 1979.

“When we were forced to do the walk-a-thons and the fundraising activities there was an incredible Oshawa Catholic High School pride within the community ... it also solidified us as a community,” he said. “It was an opportunity for people to show that this is important. When you had a walk-a-thon of that magnitude ... it was almost like a statement.”

It was during this era the Sisters of St. Joseph first sought another name change to honour Paul Dwyer — the spark that lit the school’s flame.

“Msgr. Paul Dwyer was the inspiration behind the founding of the school,” said Lauber. “He’s the one that wanted Catholic education in Oshawa.”

Although approved, Dwyer declined the honour in 1973, telling Lauber over lunch that he felt Dwyer would be too hard for immigrants to spell — something he felt conflicted with his image of welcoming new Canadians with open arms.

“He also said so many other people were involved in the establishment of the school he didn’t want to take all of the credit,” said Lauber, who saw the name change in 1976 to Paul Dwyer Catholic School following Dwyer’s death that year. “Obviously his wishes to not have the school named after him were ignored.”

Queen of Apostles is a place of Oblate hospitality

By Catholic Register SpecialMISSISSAUGA, ONT. - Queen of Apostles Renewal Centre in Mississauga is a house for people who want to reflect on themselves and to be more conscious of the presence of God in their lives.

In the tradition of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, we are committed to the search for God and to hospitality.

Queen of Apostles was designed as a retreat centre in 1963 and built on five hectares of land bordering the Credit River. We will celebrate our 50th anniversary next year. “You have every reason to celebrate,” people often say. We see their praise as a compliment and as an incentive to our daily work. Our team wants our house to be a house of hospitality. We try to create an atmosphere of wellbeing for our guests who seek a place of silence and retreat.

Loretto Maryholme on Lake Simcoe is a place of spiritual awakening

By Catholic Register SpecialROCHES POINT, ONT. - Each morning we stir in our bed, open our eyes and we are awake. We may think that “awakening” is one step, but it is really the accumulation of many steps. It begins with a pause the previous evening.

We settle into bed, our breath and heart rhythms slow and we close our eyes trusting our desire and need to rest and dream. Some time later, whether short or long, we awaken to a new day.

This is the type of awakening found at Loretto Maryholme Spirituality Centre, an awakening that acknowledges transformation as a process of meaningful stages.

Michaelite House offers peaceful setting to escape hustle and bustle

By Catholic Register SpecialLONDON, ONT. - The Michaelite House Retreat Centre is run by the Michaelite Fathers, a religious order with origins in Poland and now spreading its message of Mi-cha-el, that translates to “Who is like God” or “God above all,” around the globe.

All Hallows, where you can water your roots

By Catholic Register SpecialDUBLIN, IRELAND - A sabbatical involves taking time out from a busy routine in order to lay fallow the “land” of one’s being. It is a time, a favourable time, to turn towards God, to deepen prayer and to move towards a more contemplative stance, to put to rest all that is out of kilter in one’s life. It offers the opportunity to take stock of life and to deal with what is involved in a transition in community, ministry or parish.

All Hallows College is a Catholic and Vincentian higher education institution in Dublin, with links to colleges and universities in Europe and the United States, including De Paul, the largest Catholic university in the United States. The college prides itself on being a compact, friendly and hospitable campus. Set in six hectares of wooded parkland provides residents and guests with an opportunity for a pleasant stroll and quiet reflection.

Clarity comes with God in the discussion

By Vanessa Santilli-Raimondo, The Catholic RegisterTORONTO - Discernment has many different paths. Last Lent, my own personal discernment took me on Lenten Listening: A Busy Person’s Retreat run by Faith Connections, Regis College and the Toronto Area Vocation Directors Association. I came home with more than I bargained for but just what I needed.

Seriously contemplating whether or not I wanted to pursue freelance writing full-time, the retreat paired me up with a spiritual director in my area with whom I visited three times over the course of six weeks. Never having received any sort of formal spiritual direction before, I went into the sessions hoping to have a clearer idea of whether this was what I truly wanted.

Passing the faith down the line

By Ruane Remy, The Catholic RegisterKing City, Ont. - Every time Werner Scheliga drives away from a weekend at Marylake’s Our Lady of Grace Shrine, he leaves feeling enriched and enlightened. But 55 retreats ago, enrichment and enlightenment were not his primary concern.

It was 1956 and Scheliga had recently arrived in Canada from Germany. At just over 20 years old, he hardly spoke a word of English and knew no one. Before he left his homeland, where he was a Catholic youth leader, he was given only one name to contact — Fr. Schindler at St. Patrick’s Church in downtown Toronto.

Wives are an integral part of a deacon’s ministry

By Allison Hunwicks, The Catholic RegisterTORONTO - When Barbara and Stephen Barringer decided to announce to their children that he would be working towards becoming a deacon, their son’s immediate comment was, “Oh wonderful. Dad’s always been great at preaching and now they’re going to give him a licence!”

Deaf deacon’s trust in God helps him overcome the odds

By Erin Morawetz, The Catholic RegisterTORONTO - There’s no denying that Deacon Kevin Brockerville is a communicator.

When he talks about his wife, he smiles wide. When asked how he balances family and his deacon responsibilities, he jokes about having two ropes tied around his neck, eyes lighting up in laughter. And when he describes the people who have helped him throughout his life, his emotion is clear.

And he communicates all of this while being deaf.

Not able to hear since age three, Brockerville credits his faith with moving him forward. And it all started with a teacher in his hometown in Newfoundland.

“She would always take me to the church,” Brockerville said through an interpreter. “I didn’t really understand what church was. I would sit there and see people kneeling and praying but I didn’t know what that was.”

It was this teacher who also made sure Brockerville received the proper education.

“She found where the school for the deaf was that I could go to,” he said.

The school was in Halifax, and moving there for Brockerville was a necessary step in his spiritual journey.

“There I started understanding,” he said. “They taught religion, so I got the idea about my faith. It’s a struggle for the deaf to understand religion but I’m very happy that I had the education that helped me.”

Brockerville moved back to Newfoundland after school, and met a missionary priest from the United States who could sign.

“My mouth was wide open, I was so shocked,” Brockerville said. “‘You mean there’s a priest that can sign?’ It really inspired my wanting to serve. He’s a priest and he’s serving us.”

By the end of the 1960s, then with a wife, Gertrude, who is hearing impaired but not deaf, and his first child, Brockerville moved to Toronto for work and started attending Holy Name Church at Pape and Danforth, where the deaf ministry in Toronto gathered at the time.

“Everyone was signing and the priest was signing,” Brockerville said. “Wow, it was so powerful to me to see that everyone would come.”

The ministry has since moved to St. Stephen’s Chapel in downtown Toronto, where Brockerville serves as a deacon.

“I just felt that God was calling me to serve the deaf people,” he said about his decision to join the diaconate.

But he described his studies — culminating in his ordination in 1984 — as a “real struggle.”

“I was the only deaf person,” Brockerville said. “It was harder (for me) than (for) the hearing people because I had a hard time understanding the language.”

Brockerville explained this is a common thread for all deaf people in grasping theology, and said homilies have to be very simple when signing.

In the end, though, he made his way through the four years of diaconate study.

“I kept listening with my eyes. I kept watching,” he said. “I know that I struggled. But I had to trust God and I trust Him.”

Today, there are four locations for the deaf ministry in the archdiocese of Toronto: in Toronto, Barrie, Oshawa and Mississauga. Brockerville, who spends his time at the downtown Toronto location, is the only deaf deacon, and so has much responsibility, not only with serving at Mass and giving homilies, but also in helping deaf people with further interpretation of the services.

“Some of the deaf have questions about their faith, and if they’re studying something or reading something, I help them,” Brockerville said.

But this man — who said above his responsibilities in the diaconate and in the deaf ministry is his responsibility to his family — is anything but boastful.

“I don’t look for rewards, I look to serve,” he said. “I just follow the faith. I’m here to serve and I serve the best way I can.”

[issuu width=600 height=360 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=120910160538-19846c86f786424e98153821bd480e84 name=diaconate username=catholicregister tag=anniversary unit=px v=2]

Deacon trades street beat for hospital ministry

By Erin Morawetz, The Catholic RegisterTORONTO - For nearly 30 years, George Jurenas patrolled the streets of Toronto, keeping people safe. Today, this retired cop patrols the hallways of hospitals, giving people hope.

Jurenas was ordained a deacon in 2008, and has spent most of his time since as a chaplain at Trillium Health Centre in Mississauga and with the Peel Regional Police. And while he said his main inspiration for entering the diaconate was his own parish deacon, he recognizes his years with the Toronto Police Service showed him he had what it takes.

“People would call me Father Confessor,” Jurenas laughed. “(After I arrested people) they’d be sitting in the back of the cruiser and just seemed to open up to me naturally.”

Meeting so many different kinds of people in his profession, Jurenas said, taught him some valuable lessons.

“Over the years, what I found was people aren’t evil,” he said. “No one wants to live on the streets, no one wants to rob a bank, no one wants to put a needle in their arm. There’s usually a reason why they did what they did. There’s a hurt or a pain or something behind that action that for one reason or another placed them there.”

It’s a lesson that has helped him in many situations, like once when he was faced with a patient who, to put it lightly, did not care for his help.

“I introduced myself, said hi, I’m the chaplain, and I basically get, ‘eff off,’ ” Jurenas said.

“I said hey, no problem, God bless you. But you never know. Someone could be in a real bad place… and it’s not that they don’t ever want to talk to you, it’s just at that time.”

Jurenas never gave up on this man, and eventually they were able to turn a corner. But he’s not always so calm and collected, especially working in the palliative care ward. And it is in showing his true emotions that Jurenas sees the biggest difference between his former job and current work.

“I don’t have to pretend to be tough,” Jurenas said. “I can actually cry with people. There is strength as showing your weakness. As an officer, you (have to) play … tough, and there’s a reason for it. If you act mushy people will walk all over you.

“As an officer you’re always standing behind this façade. I’m tough, I’m in control. Then you realize none of us are really in control.”

This hit close to home for Jurenas when he was diagnosed with prostate and bladder cancer himself before becoming a deacon. He underwent an operation and radiation therapy and is now in remission, but he said the experience gave him insight into what people are feeling and going through in hospitals.

“I’ve laid in that bed,” Jurenas said. “No matter what faith you are, we’re all going through the same fears, the same worries and the same pains when we’re lying in that hospital bed.”

Jurenas uses this kind of non-denominational approach to spirituality in his chaplaincy work.

“For me as a Catholic deacon, it’s really neat when I do go visit people from other faiths, whether it be Muslim, Sikh, Hindu, you name it,” Jurenas said.

“We meet together at a certain spiritual, emotional place. Some people say does it weaken your faith? I always tell them if anything, it strengthens my faith. There’s a face of Christ in all of us.”

Jurenas saw this as particularly true when he experienced what he described as a miracle — a man who was told he had months to live walked out of the hospital a year and a half later. Jurenas and the man’s wife, a Muslim woman, had been praying together every week, he with his rosary, she with her amber beads.

“There’s a sense of respect of each other, even though we’re from different faiths and backgrounds,” Jurenas said. “It just shows you when we concentrate on what we have in common, Christ finds a way.”

Jurenas has also found humour in many situations, such as the time he came across a patient and recognized him as a former biker — one whom he had arrested at least half a dozen times in downtown Toronto.

“I used to tell him, you’re not really good at (being a criminal),” Jurenas laughed. “If (I), this beat cop, can arrest you half a dozen times, you should probably look for another line of work!”

Even former arrestees, Jurenas looked to help.

“Here’s a guy, a big feared biker. When he’d walk down the street people would move out of his way,” Jurenas said. “And all of a sudden he’s like a baby, wearing a diaper, can’t really leave the bed. It really affected him emotionally, that self-esteem drop.”

And so Jurenas went out and bought this man Harley Davidson stickers for his wheelchair.

“It was just beautiful to see, he went from this depressed state to laughing and joking,” Jurenas said. “Last thing I heard he’s at a long-term care facility and he’s scooting around.”

But ever humble, this devoted husband and father of four would never take too much credit.

“I’m basically a mirror, and I just show what you have inside of you,” he said. “At the end of the day you have to realize you’re not a superhero, you’re not a saviour. You’re just a very mortal human being.

“You do what do can.”

[issuu width=600 height=360 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=120910160538-19846c86f786424e98153821bd480e84 name=diaconate username=catholicregister tag=anniversary unit=px v=2]

Deacons have been a part of the Church since earliest days

By Erin Morawetz, The Catholic RegisterEarly Scripture makes reference to a form of the diaconate

This month marks the 40th anniversary of the arrival of the diaconate in English Canada. But the history of the diaconate actually dates back to the earliest days of the Church.

The first mention of the diaconate comes right out of Scripture, said Deacon Peter Lovrick, director of the formation program for the diaconate at Toronto's St. Augustine's Seminary, who pointed to references from St. Paul in Romans, Corinthians and Timothy in the New Testament.

But the most substantive reference to the diaconate is Acts 6:2-7, which directly refers to St. Stephen as the first deacon:

"And the twelve called together the whole community of the disciples and said, 'It is not right that we should neglect the word of God in order to wait on tables. Therefore, friends, select from among yourselves seven men of good standing, full of the Spirit and of wisdom, whom we may appoint to this task, while we, for our part, will devote ourselves to prayer and to serving the word.'

"What they said pleased the whole community, and they chose Stephen, a man full of faith and the Holy Spirit, together with Philip, Prochorus, Nicanor, Timon, Parmenas and Nicolaus, a proselyte of Antioch.

"They had these men stand before the apostles, who prayed and laid their hands on them."

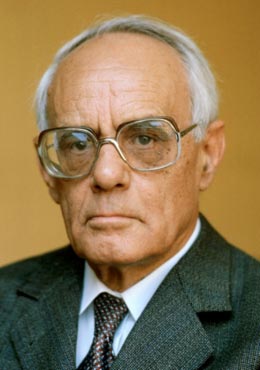

The closing session of the Council of Trent is depicted in an illustration from the 17th century.

- CNS photo/courtesy of Art Resource

Lovrick said some scholars dispute whether these words are specifically pointing towards a diaconate, though Stephen went on to become the first martyr of Christianity, and his name lives on as the patron saint of deacons.

"Many of the early fathers of the Church wrote about deacons," Lovrick said. "Deacons in the early Church had a pretty prominent role, eventually taking upon administrative and juridical positions in the Church.

"They were very closely connected to the bishops… but they were a distinct group. They were not priests."

After several centuries of deacons working closely with bishops, things started to change, said Lovrick.

"They brought in the various orders," he said. "It began to look that the deacon was a step to be a priest, and it became that way."

Today, there is a transitional diaconate, the step immediately before one becomes a priest, and the permanent diaconate, for those who do not go on to the priesthood. But before these were established as distinct ideas, the permanent diaconate began to wane by 1000, and soon disappeared in the western Church.

The Council of Trent, a council of ecclesiastical and theological experts who met in Trent to discuss important matters in the Catholic Church, was the first occasion after the original decline of the diaconate that the idea of a renewal was brought up. In 1563, during the council's 23rd session, came the call for a restoration of the diaconate, a movement that was stirred in the Eastern Catholic Churches, where the permanent diaconate had not been quite as weakened.

"The original proposal that went into the council was very ambitious and spoke a great deal about the separate order," Lovrick said. "But there were other things going on in Europe. Nothing really happened until the 20th century.

"For 500 years, (the restoration) was on hold."

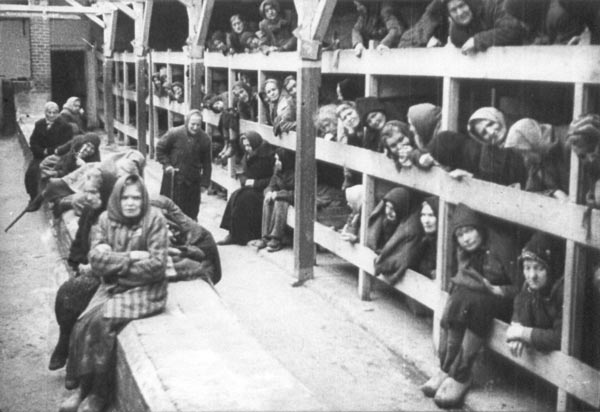

Of all places for the diaconate to begin its revival, it was the Nazi concentration camp Dachau during the Second World War. A small number of Catholic priests were detained there, in a cellblock called the "priest block." And it was there the rumblings of a new diaconate were formulated. Frs. Otto Pies and Wilhelm Schamoni spearheaded the movement.

"They saw Europe crumbling around them," Lovrick said. "They saw the ravages of war, they saw the attack on the Church.

"They had faith that we were going to get through this, but when we got through this, we would be in the ruins and things would need to be rebuilt."

These priests began to write about bringing back the diaconate envisioned at Trent, about how deacons could help the priesthood restore faith after the war. These thoughts were published, and another mind began to write about similar ideas — Fr. Karl Rahner, the great theologian.

"Rahner talked about how there were lots of people in the world doing diaconal things, but they weren't given the sacramental grace of ordination to do it," Lovrick said. "It only made sense to empower people to do what you were asking them to do. That was his basic argument."

The Dachau concentration camp was the unlikely place where talk about the revival of the permanent diaconate evolved. - CNS photo/Reuters

Meanwhile, a charitable movement in Germany called Caritas was getting very involved with restoring the diaconate by publishing articles and hosting open forums for discussion. By 1962, efforts by several groups and individuals came together with a petition for Pope John XXIII, which made its claim:

"Well-known theologians have studied the matter from the historical, theological and practical points of view, and have arrived at the consensus that the proposed restoration (1) is possible, (2) would bear great fruit in the interior life of the Church, and (3) would do much to foster the cause of unity among Christians which Christ so dearly desires."

What followed were seven questions and potential issues of reinstating deacons, and reasons and answers behind all of them; this petition set into motion the events of the Second Vatican Council. Vatican II, much like the Council of Trent, discussed the Church and its place in the modern world. It ran from 1962 to 1965, and the restoration of the diaconate was a solid fixture of discussion.

But the council did something that Trent didn't — it followed through on the diaconate discussion.

"In the (Second) Vatican (Council), 101 propositions were specifically on the diaconate," Lovrick said. "There was a lot of back and forth, some cardinals in support… others against it. But by 1964, the dogmatic document of the Church, Lumen Gentium, (had a) very clear section on the deacons calling for the restoration on the diaconate."

Four years later, in 1968, came the first ordination ceremonies of deacons since the Reformation — fittingly, in Germany. Several other countries, including Colombia, followed suit, so that by 1970 there were almost 100 permanent deacons around the world.

The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops met in Winnipeg in 1968 and voted overwhelmingly to ask Rome for permission to restore the diaconate in Canada. By 1969 it was granted.

Toronto came aboard in 1972, thus forming the first class of permanent deacons in the archdiocese of Toronto, who were ordained two years later. To date, 272 men have been ordained deacons in Toronto.

[issuu width=600 height=360 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=120910160538-19846c86f786424e98153821bd480e84 name=diaconate username=catholicregister tag=anniversary unit=px v=2]