WASHINGTON - The Second Vatican Council was “animated by a spirit of reform,” but was afraid to use the word “reform,” Church historian Jesuit Father John O’Malley told a conference marking the 50th anniversary of the opening of the council.

In its 16 documents, Vatican II used the Latin word for reform, “reformatio,” only once — in its Decree on Ecumenism when it said the Church is in need of continual reform, said O’Malley, a professor in the theology department at Georgetown University. Other than that, it preferred “softer words,” such as renewal, updating or even modernizing, he said.

O’Malley was a keynote speaker Sept. 27 at the symposium “Reform and Renewal: Vatican II After Fifty Years” held at The Catholic University of America.

The Jesuit noted that Fr. Yves Congar, a French Dominican theologian and expert on ecumenism, wrote his book True and False Reform in the Church in the 1950s that “a veritable curse” seemed to hang over the word “reform.” And when Cardinal Angelo Roncalli, the future Pope John XXIII, heard of Congar’s book, he said, “Reform of the Church; is such a thing possible?”

The Vatican’s Holy Office forbade the reprinting of Congar’s book or its translation into other languages from the original French, he said. But during Vatican II, the priest was one of many theologians helping the bishops; Pope John Paul II made him a cardinal in 1994.

O’Malley traced the history of reform in early Church councils up to and including the 16th-century Council of Trent. Trent, however, coming on the heels of the Protestant Reformation, repeatedly insisted on the Church’s unbroken continuity with the faith and practice of the apostolic Church.

“In its insistence on continuity, Trent helped develop the tradition and fostered the Catholic mindset reluctant to admit change in the course of the Church’s history and teaching,” O’Malley told an audience of about 250 people.

“By the early 17th century, Catholic reluctance to see or admit change had become deeply rooted and pervasive.”

As well, Protestants had laid claim to the word “reform” as their own, he said. The word then “suffered banishment as foreign to Catholicism and subversive of it.”

That all changed in 2005 when, shortly after his election, Pope Benedict XVI gave a speech to the Roman Curia describing Vatican II as a council of reform, rather than one of rupture with the Catholic tradition, he said.

“Reform is, according to him, a process that within continuity produces something new,” O’Malley said. “The council, while faithful to the tradition, did not receive it as inert but as somehow dynamic.”

The Church, according to Pope Benedict, grows and develops in time, but nonetheless remains always the same, he said.

In another talk, Chad Pecknold, an assistant professor of historical and systematic theology at Catholic University, traced Pope Benedict’s aversion to theories of ruptures in Church history to his research into St. Bonaventure’s theology as the young Joseph Ratzinger.

St. Bonaventure was critical of the theory of the 12th-century monk Joachim of Fiore, who maintained that there are three eras in salvation history — the Old Testament age of the Father, the clergy-dominated era of the Son and the age of the Spirit in which spiritual men would hold first place and there would no longer be sacraments or a hierarchy.

Joachim predicted the age of the Spirit would begin in 1260, Pecknold said.

For St. Bonaventure and St. Thomas Aquinas, there could only be one rupture, humanity’s redemption in Jesus Christ, he said.

Moreover, not only was Joachim wrong about history, he also was wrong about God. His theory implied that the Father, Son and Spirit are three gods acting independently.

Pope Benedict, said Pecknold, sees any interpretation of Vatican II that separates the spirit of the council from its actual teaching is to see it in the same light as Joachim’s view of history. To interpret Vatican II as a rupture with the past is, for the Pope, an interpretation which is “bound to be church-dividing and is thus non-Catholic,” he said.

(Western Catholic Reporter)

What changed at Vatican II

By Catholic Register StaffThings changed with the Second Vatican Council. No one disputes that the Catholic faith remained what it has always been. The Church still teaches what the Church always taught. But the Council did not assemble 2,860 bishops to recite the catechism. The fact that the bishops commissioned the first authoritative catechism in 350 years was just one of many changes initiated at the Council.

Among the most important changes:

- Liturgy: Vernacular languages were encouraged, especially for Scripture readings at Mass, which became far more extensive with added Old Testament readings and a cycle of three years which focusses on each of the three synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Luke and Mark). By 1969 the Novus Ordo Mass allowed priests for pastoral reasons to face the assembly, gave the celebrant a variety of eucharistic prayers, restored the sign of peace to the entire congregation, allowed for distribution of both the body and blood of Christ under the forms of bread and wine and moved tabernacles off the altars to a noble and prominent location elsewhere in the church or a separate chapel. By 1973 the International Commission for English in the Liturgy produced the first official translation of the New Mass, though various provisional translations had been circulating since the end of the Council.

- Ecumenism: Unitatis Redintegratio declared the ecumenical movement a good thing, encouraged Catholics to be part of it and referred to Eastern, Oriental and Protestant Christians as "separated brethren." In 1928 Pope Pius XI had condemned the ecumenical movement. From the Council of Trent until the Second Vatican Council Protestants were officially referred to as heretics.

- Democracy and religious liberty: In Dignitatis Humanae the Church for the first time recognized the conscience rights of all people to freedom of religion, and declared it was the responsibility of states to protect religious freedom with stable laws. The idea that the state should be neutral in religion, or that liberal democratic states could be entrusted to protect human dignity or even that there was any such thing as a right to religious freedom, had been condemned by Pope Pius IX.

- Relations with Jews: "The Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God," said Nostra Aetate. The charge of deicide was unfounded. The New Covenant is not possible without Abraham's stock.

- Relations with other religions: "The Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in these religions," said Nostra Aetate.

- Religious Life: Sisters, brothers and religious order priests were to do two things — rediscover the original purpose of their religious order and adapt it to the modern world, said Perfectae Caritatis.

- Canon Law: The Council fathers ordered a revised and written code of canon law that was finally delivered under Pope John Paul II in 1983.The Church’s past weaved into the future

By Michael Swan, The Catholic RegisterThe Second Vatican Council might be easier to understand if it had been called Back To The Future.

The two central ideas of the council appear to be headed in opposite directions. The first goes by a French title, resourcement, the second by an Italian one, aggiornamento.

Resourcement was a movement back in time. For half a century before the 1962-1965 council, theologians and many ordinary Catholics had been calling the Church back to its roots in Scripture, the early Church and even the Judaism of Jesus and His apostles. The Latin war cry on behalf of resourcement at the council was “Ad fontes!” (“To the sources!”), and one of its greatest advocates was Fr. Joseph Ratzinger. He would go on to interpret the council as a theologian, bishop, cardinal, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and now as Pope Benedict XVI.

Aggiornamento looked forward. It was how Pope John XXIII explained the basic impulse of the council. He wanted to open up the doors and windows of the Church and welcome in the world, to greet the modern age and all its cultural and technological revolutions with something more than suspicion, fear and rejection. The word means “up to the moment” in the sense of renewal.

Fifty years ago, the job of 2,860 bishops, with help from almost every significant theologian then living, was to weave the past and the future — resourcement and aggiornamento — into a seamless garment. As hard as the Church has worked to pull together those two impulses, other Catholics, conservative and liberal, have tried to pull them apart — or make one end of the spectrum more important than the other.

Liberal theologian Gregory Baum, who worked for Cardinal Augustin Bea at the Council, isn’t surprised that people want to downplay aggiornamento and all that it brought.

“There are people for whom religion means security. The world changes, everything changes, nothing is reliable,” Baum told The Catholic Register. “But the one thing that’s reliable and is unchanging is the religion they have inherited — not God, but the religion we have inherited.”

Change even small parts of their religion and you threaten people’s security, Baum said.

“It is a frightening thing,” he said.

Since the 1970s Fr. Alphonse de Valk, a conservative writer and founder of Catholic Insight magazine, has objected to the idea that the council could change the Catholic Church.

“I always supported the council,” de Valk said. “What I have attacked of course is the spirit of the council in which people said all sorts of silly things that were never discussed in the council... The ones I have opposed for these 50 years were the ones who said that the Vatican Council was a whole new beginning for the Catholic Church, and that this was something radically new, and we could forget everything we had ever been taught.”

Controversy over the council often obscures its historical context. It convened less than 20 years after the Second World War, in the shadow of the Cuban Missile Crisis, in the middle of the Cold War. At the same time, the council needs to be understood in the light of contemporary challenges to the Church, said Saint Paul University theologian and ecumenist Cathy Clifford.

“It’s probably more challenging today, even 50 years after Vatican II, because the Church is twice the size it was 50 years ago and now two-thirds of Catholics are in the southern hemisphere and non- European cultures,” she said.

From an African perspective, the Second Vatican Council was in a slightly different context. It came at the end of the colonial era, when more than 50 new nations were being born on that one continent.

“It has now become global. It’s the Church of the whole world,” Cardinal Peter Turkson told The Catholic Register. “We had a true representation of the world Church.”

For two generations after the council the African Church grew. Missionaries were replaced by local, African clergy. The continent went from 15,000 priests in 1962 to 40,000 in 2012. New dioceses with new bishops came into existence. The Novus Ordo Mass really is a new world order in Africa, with women and children dancing up the aisle to present the gifts and music that soars and thrills in natural three-part harmony pushed ahead by drums.

At the council the hierarchy of the Western Church — from the pope down through to deacons — invited the interaction of lay people. Just 24 years old in 1962, while studying theology at Toronto’s University of St. Michael’s College, Janet Somerville took up the invitation with joy and gusto. She witnessed the transformation from the days when people prayed rosaries while the Sunday readings poured off the ambo in Latin. Not just her mind, but her heart was opened by a sophisticated, scientific reading of the Bible rooted in history. At the same time, Catholics and Protestants were suddenly talking together about their faith.

“To me it felt as if the Catholic Church was renewing and reaffirming its rootedness in Scripture just in time to welcome much

more warmly the gifts of the Spirit that were flourishing in the Churches of the Protestant Reformation,” said Somerville. “I just rejoiced at that.”

She also rejoiced that a pope could cry “No More War” in an address to the entire world, as Pope John XXIII did in his encyclical Pacem in Terris. When the Vatican Council defined the Church in response to “The joy and hope, the grief and anguish of men of our time” in Gaudium et Spes, she knew it was just right.

Fifty years later it’s still just right, but bears reading again, she said. All that joy and optimism made it harder to see the full picture.

After a lifetime of work in religious journalism, a career as a CBC producer and as the first Catholic general secretary to the Canadian Council of Churches, Somerville has come to appreciate a little the conservative caution about Vatican II.

“Do I think we need more Catholic identity? Yes, I do,” she said. “But not because the Second Vatican Council wasn’t saying the things we need to know and the things we need to hear. It was. And not because we need to re-inculcate such a fear of the world and such a suspicion of the world that (the world’s) noble side and its great aspirations are as taboo in our homes as sexy advertising and consumerism and greed and living for the moment.”

There’s no shortage of people who wanted more out of the Second Vatican Council — more collegiality, more openness, more change, less centralization.

“By and large, certainly (the council) has been dealt some very serious blows,” said Jesuit Church historian John O’Malley.

But turning the counci l into a cultural battleground doesn’t advance the cause, said Clifford.

“I don’t know if disappointment is the kind of response that is helpful,” she said. “It is important to recognize that we haven’t fully received what the council taught. We haven’t fully implemented many of the structures that were provided for, even in the revision of the Code of Canon Law that followed the council. In some ways, we’ve received the council in a minimalist way.”

Hope is the response that Pope Benedict XVI has tried to foster.

“Many people have given up the fight. Many people have just lost interest, which is even worse,” said Somerville. “Pope Benedict XVI has a very interesting balance in the way he never rejects the council but does not put any short timelines on any of the victories we were confidently expecting.”

Hope was how it all started.

In 1959 Pope John XXIII first discussed with a few of his cardinals just what he had in mind. He told them: “I am thinking of the care of the souls of the faithful in these modern times... I am saddened when people forget the place of God in their lives and pursue earthly goods as though they were an end in themselves. I think, in fact, that this blind pursuit of the things of this world emerges from the power of darkness, not from the light of the Gospels, and it is enabled by modern technology. All of this weakens the energy of the spirit and generally leads to divisions, spiritual decline and moral failure. As a priest, and now as shepherd of the Church, I am troubled and aroused by this tendency in modern life and this makes me determined to recall certain ancient practices of the Church in order to stem the tide of this decline. Throughout the history of the Church, such renewal has always yielded wonderful results.”

The good pope was not speaking as a theologian, but as a pastor. A year into his own papacy, Pope Benedict gave a name to Pope John’s hopeful, pastoral impulse. He called it the “hermeneutic of reform.”

“With the Second Vatican Council the time came when broad new thinking was required. It’s content was certainly only roughly traced in the conciliar texts, but this determined its essential direction so that the dialogue between reason and faith, particularly important today, found its bearings on the basis of the Second Vatican Council,” he said.

Hermeneutic is a technical term in philosophy meaning a method of interpretation. Benedict famously contrasted interpretations of the Council based on reform with interpretations based on “discontinuity and rupture.” It is wrong to imagine the Church somehow started again in 1962, or that the Church before the Council was a different Church. There is only one mystical body of Christ, and it is the same through all time.

The movers and shakers behind the Second Vatican Council

By Catholic Register StaffThe Second Vatican Council was the biggest stage in the history of the Church. There were more bishops present than at any the 20 previous councils stretching from the First Council of Nicaea in 325 to the First Vatican Council of 1870. And the bishops present came from more countries, more cultures, more languages than the Church had ever experienced.

A Church reborn: The 50th Anniversary of Vatican II

By Glen Argan, Canadian Catholic NewsOn Jan. 25, 1959, a new pope shocked the world. Pope John XXIII, speaking to a small group of Roman cardinals following a liturgy to conclude the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, announced that he had decided to convene an ecumenical council.

Pope John, elected less than three months earlier, had previously told only one person of his plan and had consulted with no one else. He had little ideaof why he wanted a council. He did however refer to “the strengthening of religious unity and the kindling of a more intense Christian fervour.”

The Church, he said, was on the threshold of a new era in history when it would be necessary “to define clearly and distinguish between what is sacredprinciple and eternal Gospel and what belongs rather to the changing times.”

With those comments, Pope John struck a few notes that would eventually help to characterize the much-maligned “spirit of Vatican II,” but not until after concerted resistance from the Vatican’s own Curia had been overcome.

Essentially, the Pope’s decision to call the council was an inspiration or an intuition that such a great gathering was needed. When the council finally opened on Oct. 11, 1962, he said the idea for the council had come “like a flash of heavenly light” . . . “a sudden emergence in our heart and on our lips of the simple words ‘ecumenical council.’ ”

Few, if any, ranking churchmen in early 1959 believed that a council was necessary. In the past, councils had been called to respond to crises in the Church, especially over doctrine. But now there was no doctrinal crisis nor was there a pastoral crisis. The Church was apparently in wonderful shape, certain of its teaching and, throughout the Western world, its worship halls were full.

Moreover, after the First Vatican Council in 1870 had declared the doctrine of the infallibility of the Pope, many believed that there would never again be a need for a worldwide council. Gotta problem? The Pope will solve it with a clear, unequivocal declaration.

But Pope John did call a council. And what a council it was! Fifty years later, its reverberations are still being felt throughout the Church. Indeed, the debate over what the council said and meant is ongoing, even increasing in fervour. The process of implementing the council is still incomplete.

Today, the 16 documents of the Second Vatican Council form a foundation for the life of the Church. But if in 1965 those documents seemed almost revolutionary, today they seem less so.

Angelo Giuseppi Roncalli became a pope like no other in the 20th century. He rose to become Pope John XXIII basically under the radar and was formed by a unique set of experiences that helped him understand that the action of the Holy Spirit is not confined to the Catholic Church.

He was not a radical or even an innovator. Judged by today’s standards, his public comments and private correspondence can only be described as quite conservative. While his papacy had a markedly different style than that of Pope Pius XII, his reserved predecessor, Pope John seems to have taken only one off-the-wall action in his life — to convoke Vatican II.

In October 1958, Pope Pius XII died after years of illness. Roncalli was quickly seen as one of the leading candidates to be his successor. Why? First, at age 76, he would be a transitional pope after Pius’ long 19-year pontificate. Second, he was not part of the Vatican power structure that had grown too strong in Pius’ declining years. Third, he was seen as a bridge-builder, someone who would be accessible to the cardinals and a pastor to the people.

Further, although he was 76, Roncalli was actually one of the younger cardinals. Pius had held only two consistories to appoint new cardinals during his long pontificate. With only 51 cardinals entering the conclave and many of them quite elderly, the pool of papal candidates was small.

Still, it took 11 ballots before he was finally elected. Why the hesitation? Some, it appears, felt Roncalli lacked the intellectual heft to lead the Church, even for a short period. Nevertheless, he was elected and chose the name John. Less than three months later, this “transitional pope,” without consulting anyone other than the Holy Spirit, started the wheels in motion for the Second Vatican Council.

Recently, a group of scholars published a book, Vatican II: Renewal Within Tradition. The book examines the 16 documents in some detail, carefully pointing out that the council did not erase what came before it. The teachings of Vatican II are totally in continuity with what the Church had taught previously. There is evolution and development of doctrine, but no radical break with the past.

This may be true, but those old enough to remember the Church before Vatican II, and who recall the earthquake that it represented in the life of the Church, cannot be satisfied with such a placid account.

Franciscan Father Don MacDonald, who teaches a course on Vatican II at Newman Theological College in Edmonton, believes Vatican II has been misunderstood. Some believe the purpose of the council was to make being a Catholic easier and to help Catholicism adapt to the modern world. That’s wrong on both accounts.

The Church has never tried to adapt itself to the world, MacDonald said, and the council made the faith more demanding, “in the best sense of the word.” The Church before Vatican II was not the good ol’ days, he said. A lot needed to change.

In the seminary, MacDonald recalls being taught that how a priest celebrates Mass was more important than what was being celebrated. The emphasis placed on how the priest held his hands during Mass “was almost like a phys-ed exercise.”

Still, there was a lot of “heroic Catholicism” and a strong emphasis on social action in the Church prior to the council, he said. “You have to have respect for that pre-Vatican II faith.”

There is more to Vatican II than what is found by studying its documents. If there was doctrinal continuity in the council’s teachings, there was also an enormous upheaval in the life of the Church. Some of that upheaval may well be due to misinterpretations and over-enthusiasms. Part of it is no doubt the result of a greater embracing of Western culture which, in the 1960s, underwent massive convulsions.

But above and beyond all that, a sea change took place in the Church that was necessary and productive.

The liturgy underwent a process of revitalization that is still continuing. Greater contact with non-Catholic Christians and people of other faiths was encouraged. A static, deadening approach to theology was jettisoned in favour of one that allowed room for inquiry and evolution.

The Church endorsed religious liberty and rejected the notion that error has no rights. The full equality of the People of God in Baptism was recognized and holiness was seen as God’s call to everyone, not just a spiritual elite. There was, in short, greater openness and less fear of “enemies.”

For many, that openness was disorienting. When the central religious rituals of one’s life are altered, it is likely to deeply unsettle one’s relationship with the Transcendent. That fact and the effects of other changes were not sufficiently appreciated in the mid- 1960s. These are likely not the only causes of a mass exodus of priests and religious from their callings and laity from regular Church attendance. But an honest evaluation of the changes should see them as contributing factors.

Still, a reform of the liturgy was necessary and perhaps overdue. As well, it must be said that one can be faithful to the letter of the Church’s teachings and still acknowledge a legitimate “spirit of Vatican II” that is in harmony with those teachings. It is impossible to tell the full story of Vatican II without acknowledging its history and without trying to come to grips with that legitimate spirit.

Communications and transportation networks were far less developed 50 years ago. As well, the Church’s theology of collegiality among bishops was practically non-existent and there were few joint episcopal efforts. When the bishops arived at Vatican II in 1962, many were meeting prelates from around the world for the first time.

Canada’s bishops and Catholic universities were among those who responded to the Vatican’s call in 1959 for input about topics to be considered at the Second Vatican Council. Canada was a far different country then and the same could be said for the Canadian Church. If parishes and dioceses today seem to be somewhat isolated cocoons, it’s nothing compared with the situation prior to Vatican II.

Given all that, it is perhaps not surprising that suggestions from Canada’s bishops lacked vision. In the mid-1990s, Michael Fahey of the University of St. Michael’s College in Toronto examined the input of the Canadian bishops prior to the council. For the most part, it reflected “notably weak” theology and the “generally poor state of collegiality in Canada,” Fahey wrote in L’Eglise canadienne et Vatican II (edited by Gilles Routhier). But what is remarkable, he noted, is the extent to which their vision was transformed by the time Vatican II ended in 1965.

What did the Pope expect out of Vatican II? Raised in the tiny village of Sotto il Monte by peasant farmers who kept cows in their house, Pope John had the audacity to convoke an ecumenical council of the entire Roman Catholic Church. Moreover, he didn’t even have a plan for this whimsical council. But he said it would provide for “the enlightenment, edification and joy of the entire Christian people” and that the faithful of other Christian churches would be invited too.

The Pope said the idea to call the council came to him “like a flash of heavenly light.” Other Church leaders felt quite in the dark.

Pope John was known for his sense of humour and his positive outlook on life. Perhaps it was these factors that led him to say, two years after his Jan. 25, 1959 announcement that the Church would hold a worldwide council, that the announcement was greeted by the cardinals present with “a devout and impressive silence.”

No applause greeted the papal announcement in the Basilica of St. Paul. Church historian Giuseppe Alberigo says the reaction of the 17 cardinals present was “characterized by bewilderment and worry.”

No one in the know could see any reason for a council. For the Rome-based cardinals, who had run their offices at the Vatican with little oversight from the ailing Pope Pius XII for several years, a general council could only mean trouble. The Vatican would be flooded with bishops from around the world, bishops unfamiliar with Roman ways, the vast majority of whom the cardinals themselves did not know.

Even Cardinal Giacomo Lecaro of Bologna, who would later become one of the progressive leaders at Vatican II, groused, “How dare he summon a council after 100 years and only three months after his election? Pope John has been rash and impulsive. His inexperience and lack of culture brought him to this pass, to this paradox.”

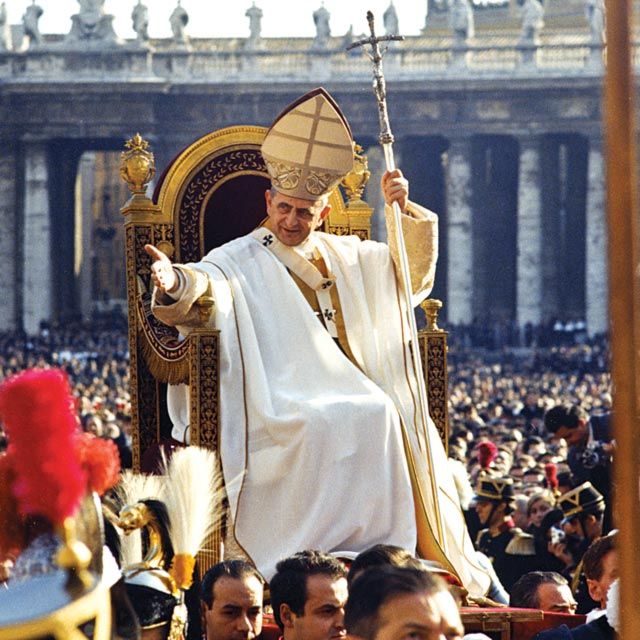

Cardinal Giovanni Battista Montini, later Pope Paul VI, was initially cool to the call for a council. But perhaps inspired by the excitement in his Milan archdiocese, he wrote a pastoral letter stating, “A flame of enthusiasm swept over the whole Church. He understood immediately, perhaps by inspiration, that by calling a council he would release unparalleled vital forces in the Church.”

If many cardinals were dubious about the council, the rest of the world was not. Almost spontaneously, people around the world — Catholic and non-Catholic — saw the council as a great sign of hope and renewal in the Church. The expectation created overnight was tremendous.

(Western Catholic Reporter)

Councils date back to early days

By Michael Swan, The Catholic RegisterThe model for all ecumenical councils is the Council of Jerusalem, recalled in the Acts of the Apostles, chapter 15. However, it is not generally listed as one of the 20 ecumenical councils of Church history. Ecumenical (from the Greek word oikoumene) means worldwide, and the first one was called by the Emperor of the known world, Constantine I.

1. First Council of Nicea in 325 defined the heresy of Arianism.

2. First Council of Constantinople in 381 again repudiated Arianism.

3. Council of Ephesus in 431 declared Mary as "God carrier" or Theotokos.

4. Council of Chalcedon in 451 made more explicit that Jesus' divine and human natures were united in a single being.

5. Second Council of Constantinople in 553 condemned Origen of Alexandria, the first great Scripture scholar of Christianity, for some odd ideas he had about the transmigration of souls.

6. Third Council of Constantinople in 680-681 dealt with more threats to unity of Christ, specifically a theory that Jesus had two wills — one divine and one human — but one nature. Monothelitism was condemned as heresy.

7. Second Council of Nicea in 787 tried to stop people from going around smashing icons. Veneration of icons was defined as good and iconoclasm was condemned.

8. Fourth Council of Constantinople in 869-870 restored St. Ignatius to his throne as Patriarch of Constantinople.

9. First Lateran Council in 1123 excommunicated the Holy Roman Emporer Henry V and declared it heresy for kings, princes and even the Holy Roman Emporer to appoint bishops. This was known as the investure controversy and it went on for centuries. The council also tried to impose celibacy on secular priests.

10. Second Lateran Council in 1139 was another attempt to get kings out of the business of the Church, and also tried to reform the clergy, including another condemnation of marriage among priests.

11. Third Lateran Council in 1179 condemned the sale of sacraments and positions in the hierarchy (simony) and declared only cardinals could elect the pope.

12. Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 defined transubstantiation, a term that remained controversial at the Second Vatican Council.

13. First Council of Lyon in 1245 excommunicated and deposed Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II who had put Rome under siege. Pope Innocent IV also used the Council to strike an alliance with King Louis IX of France and launch the Seventh Crusade under the French king's command.

14. Second Council of Lyon in 1274 under Blessed Pope Gregory X tried to repair the Great Schism of 1054. However, Greek Orthodox bishops were condemned for attending the Council when they returned home.

15. Council of Vienna in 1311 to 1312 marked the end of the crusades. The Knights Templar lost their Church support and Franciscan Ramon Llull (Raymond Lully) convinced the Council fathers the only way to retake the Holy Land was to learn the languages — specifically Hebrew, Arabic and Greek.

16. Council of Constance in 1414 to 1418 had to solve the problem of three popes: Anti-pope John XXIII, Avignon Pope Benedict XIII and Pope Gregory XII had all been elected by some bishops in a situation known as the Western Schism of 1378 to 1417. The Council of Constance resolved the schism by declaring an ecumenical council is a higher authority even than the pope who convokes it and then installing Pope Martin V.

17. Council of Florence opened in 1431 in Basel with no bishops, moved to Ferrara, Florence and finally Lousanne. There were wars in Bohemia, a rising threat in the Ottoman Empire and plague. The council tried to assert the idea of conciliarity, that councils should be part of the normal governance of the Church, and it achieved a short-lived reconciliation with some Greek Orthodox bishops and the Armenian Church.

18. The Fifth Lateran Council, the last before the Reformation, from 1512 to 1517 amounted to a battle royal between the forces of conciliarism and Pope Julius II's convictions about papal authority. Master of the Dominican order Thomas Cajetan argued for absolute papal authority against University of Paris theologian Jacques Almain. The Council passed a decree backing Cajetan's position.

19. Council of Trent from 1559 to 1565 tried to answer the challenge of Martin Luther, but came along too late to reunite a divided Western Church. The council's doctrine of salvation, definitions of the sacraments and reforms to the liturgy defined Catholicism for 350 years. It initiated the Catechism of 1568, a new Roman Missal which defined the Tridentine Mass, issued a new edition of the Vulgate — the Bible in Latin — and pronounced a long series of anathemas. It also envisioned the seminary system in the hope of a better educated clergy and encouraged the Mass in local languages, a reform that had to wait for the Second Vatican Council.

20. First Vatican Council of 1869 to 1870 defined papal infallibility. Papal infalibility was then used in 1950 by Pope Pius XII to declare the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven a universally accepted dogma of the Church.

21. Second Vatican Council of 1962 to 1965 was convoked after the Second World War and during the Cold War by Blessed Pope John XXIII.

The documents that came out of Vatican II

By Catholic Register StaffConstitutions:

o The Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation (Dei Verbum) is about how Catholics read the Bible and the role of scholarship. Key quote: The tradition that comes from the apostles makes progress in the Church, with the help of the Holy Spirit. There is growth in insight into the realities and words that are being passed on.

o The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church (Lumen Gentium) defines the Church as the people of God. Key quote: At all times and in every race, anyone who fears God and does what is right has been acceptable to Him (cf. Acts 10:35). He has, however, willed to make men holy and save them, not as individuals without any bond or link between them, but rather to make them into a people who might acknowledge him and serve him in holiness.

o The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes) defines the Church's relationship with the present age and culture. Key quote: The joy and hope, the grief and anguish of the men of our time, especially of those who are poor or afflicted in any way, are the joy and hope, the grief and anguish of the followers of Christ as well. Nothing that is genuinely human fails to find an echo in their hearts.

o The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (Sacrosanctum Concilium) sets out a framework for liturgical reform. Key quote: Mother Church earnestly desires that all the faithful should be led to that full, conscious and active participation in liturgical celebrations which is demanded by the very nature of the liturgy, and to which the Christian people, "a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a redeemed people" (1 Peter 2:9, 4-5) have a right and obligation by reason of their baptism.

Decrees:

o The Decree on the Church's Missionary Activity (Ad Gentes) recalibrates missionary activity with a new respect for non-Christian cultures. Key quote: Some of these men are followers of one of the great religions, but others remain strangers to the very knowledge of God, while still others expressly deny His existence, and sometimes even attack it. The Church, in order to be able to offer all of them the mystery of salvation and the life brought by God, must implant herself into these groups for the same motive which led Christ to bind Himself, in virtue of His Incarnation, to certain social and cultural conditions of those human beings among whom He dwelt.

o The Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity (Apostolicam Actuositatem) charges lay Catholics with a duty and responsibility to transform the world. Key quote: The Holy Spirit sanctifies the People of God through the ministry and the sacraments. However, for the exercise of the apostolate he gives the faithful special gifts besides (cf. 1 Corinthians 12:7), "allotting them to each one as he will" (1 Corinthians 12:11), so that each and all, putting at the service of others the grace received, may be "as good stewards of God's varied gifts" (1 Peter 4:10) for the building up of the whole body of charity (cf. Ephesians 4:16).

o The Decree on the Pastoral Office of Bishops in the Church (Christus Dominus) calls bishops to be the principal teachers of the faith in their dioceses and encourages them to work together. Key quote: Bishops should devote themselves to their apostolic office as witnesses of Christ to all men. They should not limit themselves to those who already acknowledge the Prince of Pastors but should also devote their energies wholeheartedly to those who have strayed in any way from the path of truth or who have no knowledge of the Gospel of Christ and of His saving mercy, so that ultimately all men may walk "in goodness, justice and truth." (Ephesians 5:9)

o The Decree on the Means of Social Communication (Inter Mirifica) declares that the first and best purpose of media is to preach the Gospel by word and deed. Key quote: First of all, a responsible press should be encouraged. If, however, one really wants to form readers in a truly Christian spirit, an authentically Catholic press ought to be established and supported.

o The Decree on the Training of Priests (Optatam Totius) envisions the kind of priests the Church will need as it begins to embrace and encourage the modern world rather than reject it. Key quote: "Notwithstanding the regrettable shortage of priests, due strictness should always be brought to bear on the choice and testing of students. God will not allow his Church to lack ministers if the worthy are promoted and those who are not suited to the ministry are guided with fatherly kindness and in due time to adopt another calling. These should be directed in such a way that, conscious of their Christian vocation, they will zealously engage in the lay apostolate.

o The Decree on the Catholic Oriental Churches (Orientalium Ecclesiarum). Rather than stalking horses for an eventual Catholic triumph in the East, Eastern Catholic Churches are urged to fully embrace their liturgical and theological traditions as particular Churches or rites. Key quote: History, tradition and very many ecclesiastical institutions give clear evidence of the great debt owed to the Eastern Churches by the Church Universal. Therefore the holy council not merely praises and appreciates as is due this ecclesiastical and spiritual heritage, but also insists on viewing it as the heritage of the whole Church of Christ. For that reason this Council solemnly declares that the Churches of the East, like those of the West, have the right and duty to govern themselves according to their own special disciplines.

o The Decree on the Up-To-Date Renewal of Religious Life (Perfectae Caritatis) calls on nuns, brothers and religious order priests to rediscover the original charisms of their founders and to find an expression of the vows which embraces the Lumen Gentium vision of the Church in the modern world. Key quote: The up-to-date renewal of the religious life comprises both a constant return to the sources of the whole of the Christian life and to the primitive inspiration of the institutes, and their adaptation to the changed conditions of our time.

o The Decree on the Life and Ministry of Priests (Presbyterorum Ordinis) taught that priests do not exercise their ministry for their own sake but for the sake of building up the Christian community. Key quote: Priests, while being taken from amongst men and appointed for men in the things that appertain to God that they may offer gifts and sacrifices for sins, live with the rest of men as with brothers. So also the Lord Jesus the Son of God, a man sent by the Father to men, dwelt amongst us and willed to be made like to his brothers in all things save only sin.

o The Decree on Ecumenism (Unitatis Redintegratio) declares Christian unity a primary responsibility of the Catholic Church. Key quote: Christ the Lord founded one Church and one Church only. However, many Christian communions present themselves to men as the true inheritors of Jesus Christ; all indeed profess to be followers of the Lord but they differ in mind and go their different ways, as if Christ Himself were divided. Certainly, such division openly contradicts the will of Christ, scandalizes the world, and damages that most holy cause, the preaching of the Gospel to every creature.

Declarations

o The Declaration on Religious Liberty (Dignitatis Humanae) commits the Church to the human right of freedom of religion. Key quote: The Vatican Council declares that the human person has a right to religious freedom. Freedom of this kind means that all men should be immune from coercion on the part of individuals, social groups and every human power so that, within due limits, nobody is forced to act against his convictions nor is anyone restrained from acting in accordance with his convictions in religious matters in private or in public, alone or in associations with others.

o The Declaration on Christian Education (Gravissimum Educationis) stakes a claim for the Church's right to provide education as a social good to society as a whole. Key quote: All men of whatever race, condition or age, in virtue of their dignity as human persons, have an inalienable right to education. This education should be suitable to the particular destiny of the individuals, adapted to their ability, sex and national cultural traditions, and should be conducive to fraternal relations with other nations in order to promote true unity and peace in the world.

o The Declaration on the Church's Relations with Non-Christian Religions (Nostra Aetate) fundamentally changed the Church's relationship with Jews and with other religions. Key quote: The Catholic Church rejects nothing of what is true and holy in these religions. She has a high regard for the manner of life and conduct, the precepts and doctrines which, although differing in many ways from her own teaching, nevertheless often reflect a ray of that truth which enlightens all men.

Canadian influence unmistakable at Vatican II

By Michael Swan, The Catholic RegisterRome on Oct. 11, 1962, but the drama started in Canada Aug. 17 that year.

For a year and a half Cardinal Paul-Emile Leger, archbishop of Montreal, had been one of a handful of cardinals on the central preparatory commission of the council. It had met seven times between June 1961 and the feast of Pentecost, 1962. And then Leger received his book of draft documents assembled by curial officials in Rome.

Leger was not pleased with what he saw. On Aug. 17 he launched a “supplique” — a letter of petition — addressed directly to Pope John XXIII. Leger told the Pope in no uncertain terms the documents prepared in Rome were unworkable, impractical and simply wrong. They were wrong in their tone, their language and their limited vision. The council must present the traditional faith of the Church pastorally. For Leger, it was imperative the council find new modes of expression. Leger’s “supplique” eventually gathered the signatures of a number of heavyweights in the College of Cardinals.

On Sept. 17 Leger got a message back through Cardinal Amleto Cicognani, the Vatican’s Secretary of State, saying that the Pope had favourably received the supplique. How favourably became clear when the Pope opened the council on Oct. 11. Pope John XXIII immediately emphasized conciliarity by recalling that council had been throughout history the highest teaching authority in the Church. Then the Pope took a swipe at cautious, gloomy curial officials who would rather not address the modern world.

“We feel that we must disagree with these prophets of doom, who are always forecasting worse disasters, as though the end of the world were at hand,” said the Pope.

But Canadian influence on the council did not stop there.

“One of the key elements of the council is conciliarity within the Church. And one of the major voices promoting conciliarity within the council is Maxim Hermaniuk. It’s clear as night and day,” said Fr. Myroslav Tataryn, St. Jerome’s College professor of Church history.

Hermaniuk was the Ukrainian Metropolitan Archeparch of Winnipeg, and he chaired the 15-member Ukrainian Catholic delegation. He called for a permanent synod of bishops to collaborate regularly with the pope. He favoured presenting the liturgy in local languages. He fought for respect for the 21 non-Roman rites of the Catholic Church and championed the cause of ecumenism by pointing out the theological irrelevance of the mutual ex-communications between the patriarch of Rome and the patriarch of Constantinople in 1054.

As an Eastern Catholic Hermaniuk knew the spiritual and practical value of synods.

“He recognized that (synods) are not just something the Eastern Churches hold dear. It is part of the apostolic heritage,” said Tataryn. “It is the way in which the early Church operated. It doesn’t take anything away from Peter. It doesn’t take anything away from the Roman papacy. It is simply a recognition that the fullness of the Church’s life is expressed in that balance.”

He never got the permanent synod of bishops, but Hermaniuk started a conversation that goes on to this day.

“So Hermaniuk put out the proposal. It gets formulated in different ways. We still haven’t worked out how synodality works in the Catholic Church today,” said Tataryn.

German-born Canadian theologian Gregory Baum played a central role in drafting the first text on the relationship between Christians and Jews — a document that would eventually become Nostra Aetate.

Baum’s involvement began at a meeting with Cardinal Augustin Bea to discuss ecumenical relationships with non-Catholic Christians.

“At the end of the meeting Cardinal Bea said, ‘I just saw the Pope, and he said to us that he wants the secretariat to prepare a statement to rethink the Church’s relationship to the Jews,’ ” Baum recalled in an interview with The Catholic Register.

Bea was looking for experts who could contribute and Baum had published a book on the subject. From that point forward Baum worked closely with Bea.

Baum is incredulous when people suppose that somehow wily, elite, academic theologians were leading the bishops along at the council.

“These things came from the very top. The theologians were asked to help in this, to write texts and so on, but the initiative came from the top,” he said.

“It would be quite wrong to think this was run by theologians.”

Canadian bishops who had roles in helping to prepare for the council included Quebec Archbishop Maurice Roy (who was made a cardinal at the end of the council), Toronto Auxiliary Bishop Philip Pocock (who became Toronto’s archbishop in 1971), Winnipeg Archbishop George Flahiff (who was made a cardinal in 1969) and Sault Ste. Marie Bishop Alexander Carter.

Pocock was a consultor to the Commission for the Discipline of the Clergy and the Christian People. Once he held the reins in Toronto, he put his Vatican II experience into action by ordaining deacons. Pocock’s model of the revived diaconate survives to this day and is imitated all over North America.

Carter dedicated the rest of his life to lifting up the laity, creating the Diocesan Order of Service and the Diocesan Order of Women. He empowered women and native elders to preside at communion services when no priest is available, minister to the sick, witness weddings, baptize and lead wake services.

Carter was “entirely transformed by it,” said Michael Attridge, a University of St. Michael’s College theologian and historian of the council.

“He saw himself as someone who needed to implement the council in the diocese of Sault Ste. Marie in the years following,” Attridge said.

As a young priest studying canon law at The Angelicum (the University of St. Thomas Aquinas in Rome) during the council, retired Hamilton Auxiliary Bishop Matthew Ustrzycki witnessed a whole new side of the Church. The pre-Vatican seminaries of North America were not hotbeds of controversy and debate, but in Rome people were arguing theology in the street.

All the passion and idealism of the council took place against a backdrop of imminent doom. The Soviet Union had tried to install nuclear missiles just a few miles off the American coast in Cuba. Memories of the Holocaust and Europe at war were fresh. Communism and capitalism had the world divided in half.

But the Second Vatican Council wasn’t just about bishops and theologians. It addressed itself to the whole world, and Canadians took that very seriously.

“It helped us to understand the call to justice,” said Saint Paul University theologian Cathy Clifford. “That solidarity with the poor and the call to justice were an integral part of our faith commitment. I don’t hear that as much today.”

The times called forth optimism from Canadians, recalls Janet Somerville, retired general secretary of the Canadian Council of Churches.

“We were tremendously optimistic about our heritage and our future at that time,” she said. “That did condition the way we read the texts of the council.”

Canada’s middle class was growing and Catholics were joining it in record numbers. And that meant a sea change in Catholic attitudes, said Somerville.

The tragic world view of suffering immigrant Catholics was on its way out as the council convened.

“Catholics were sociologically emerging from that during the ’60s,” said Somerville. “They kind of identified the council’s agenda with their own agenda of being much more satisfied with the world — because the world was treating them better.”

Much of the Canadian history of Vatican II is still being written in how the council is interpreted. Winnipeg Archbishop James Weisgerber tells anybody who will listen that it takes 100 years to understand and implement an ecumenical council. As a historian, Attridge is trying to understand how three generations of bishops — the ones who participated in the council, the ones ordained shortly after and the bishops in place now — have interpreted Vatican II.

“It would be interesting to map the change in the Canadian bishops as we move further away from the council,” he said.

“In general, councils don’t happen very often,” said Clifford. “Even to understand what a council is and how a council deliberates is something.