Students at an Ottawa elementary school will be getting a full-day pass from the regular classroom in order to go to school on sainthood when Kateri Tekakwitha is canonized.

On Oct. 22, the day after Kateri is made a saint by Pope Benedict XVI in Rome, Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Elementary School students will put away their math books and readers to spend the whole day studying St. Kateri and the process of canonization. They’ll watch videos from the Oct. 21 ceremony in Rome, hear about the school’s connection to Kateri and learn about her extraordinary life and culture from former teacher Line Douglas.

“She lived her faith and was devoted to others, caring for the elderly and the infirm while the others went about their business in the spirit of love and simplicity,” said Douglas, 70, explaining what she’ll tell the students. “She was so intense and so devoted. She was in love with the sublime, with God and did everything in such an admirable, straightforward, pure way.”

The day of learning is part of a two-month school celebration that will culminate when the school is renamed Saint Kateri Tekakwitha in late November. Similar renaming ceremonies will also occur at Blessed Kateri Catholic Elementary School in Hamilton, Ont., Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Catholic School in Toronto and Kateri Tekakwitha Catholic Elementary School in Markham, Ont.

But the Ottawa school is taking things a step further.

“We’ve got multiple events,” said principal Paul Gautreau. “We’re using it as an opportunity for our kids to learn about Kateri and learn about what is a saint.”

The program started after the Thanksgiving long weekend when the student body, about 200 strong, were asked daily questions about Kateri, he said.

“We really want students’ voices to come through. We aren’t necessarily looking for the right answer, we want to know what they know as a starting point.”

Douglas, a descendent of the Mohawk nation, began teaching at Blessed Kateri in 1986 when the school opened. She retired in 1998. During her tenure at the school, Douglas worked hard to teach her students about Kateri’s devotion, dedication to faith despite social oppression and love of nature.

“I hoped that she rubbed off on me,” said Douglas. “I just love Kateri. I have a devotion to her.”

In the month leading up to the renaming of the school, a member of the Mohawk nation will frequent the Ottawa school to deepen the children’s knowledge of Kateri. They’ll study native culture and the challenges Kateri faced practising her faith in a 17th-century native culture.

They’ll also learn native drumming, which they will perform during the Nov. 29 renaming ceremony where traditional aboriginal refreshments and snacks will be served.

“Part of the reason for (the Nov. 29 date) is that many of people who we are going to ask to come here will actually be in Rome for the canonization,” said Gautreau.

Those who will be in Rome include Ottawa Archbishop Terrence Prendergast, a Mohawk leader and an Algonquin leader who once owned the land the school is located on.

Gautreau said he hopes the lessons continue after the school is renamed because he feels there is a lot his students can learn about their faith from Kateri.

“I hope that these celebrations will provide a little spark that will help things to just keep moving forward,” he said. “She was extremely faithful in challenging circumstances in that she renewed her faith in those challenging circumstances. That’s a message we can hopefully bring to the students.”

Patience, love guided Kateri’s promoter

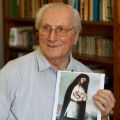

By Cindy Wooden, Catholic News ServiceVATICAN CITY - Although separated from her by three centuries, an ocean and major cultural differences, Jesuit Father Paolo Molinari absolutely loves Kateri Tekakwitha, the Native American who becomes a saint Oct. 21.

While the 88-year-old Italian Jesuit was forced to give his successor most of the sainthood causes he still was actively promoting when he turned 80, “thank God, they let me keep Kateri.”

Molinari, one of the Church’s most prolific postulators — as the official promoters of causes are called — inherited Kateri’s cause from his Jesuit predecessor in 1957. He shepherded her cause to beatification in 1980.

“I love her. She’s a lovely young lady indeed,” said the Jesuit, his eyes sparkling.

Molinari said his admiration for Kateri, combined with the complex Vatican process for declaring saints and the fact that she died some 330 years ago, gave him 55 years to practice the virtue of patience. But unlike many of the so-called “ancient causes” that are surrounded by pious legends, but lacking hard evidence, Kateri’s cause was supported by plenty of eyewitness accounts of her life, faith, good works and death.

The Jesuit missionaries who baptized her in 1676 and provided her with spiritual guidance until her death in 1680 at the age of 24 wrote formal annual reports about their missions to the Jesuit superior general. Kateri, known as the “Lily of the Mohawks,” is mentioned in many of the reports, which still exist in the Jesuit archives, he said.

Molinari also had access to the Jesuits’ letters that spoke about Kateri in glowing terms and to biographies of Kateri written by two of the Jesuits who knew her at the Mission of St. Francis Xavier in what is now Kahnawake, Que. Frs. Pierre Cholenec, her spiritual director, and Claude Chauchetiere, who also did an oil painting of Kateri shortly after her death.

Kateri was born to a Catholic Algonquin mother and a Mohawk father in 1656 along the Hudson River in what is today upstate New York.

After her baptism, Molinari said, “she kept living the life of a normal Indian. She continued to be an Indian young lady, and yet she did it with the spirit of the Gospel: showing goodness and tenderness to people who were in need.”

She suffered from light sensitivity after contracting smallpox, so would spend much of her time inside. She prayed and made garments out of hides for those who were unable to make their own, he said.

Molinari said that although the cause was challenging at times, he kept working for Kateri’s canonization because of her importance to the native peoples of North America.

Kateri is a model who can “help those who are Christian live the Gospel in their own culture.”

The Catholic Church, he said, “is the first organization that has acknowledged the richness of one of their own people. The U.S. and Canadian governments have never done anything like that.”

Once Kateri was beatified, Molinari’s efforts turned to helping more people learn her story, encouraging people to trust that she could intercede with God to help them and finding an extraordinary grace that could be recognized officially as a miracle granted by God through her intercession.

The Jesuit said that in the sainthood process, miracles are “the confirmation by God of a judgment made by human beings” that the candidate really is in heaven.

In Kateri’s case, the recognized miracle was the healing of five-year-old Jake Finkbonner from a rare and potentially fatal disease, a flesh-eating bacteria called necrotizing fasciitis. The boy and his family are members of St. Joseph parish in Ferndale, Wash., in the Seattle archdiocese.

“Kateri lived 300 years ago and yet she is widely remembered with love and admiration to the point that people believe she is certainly with God because of the way in which, as an Indian woman, she opened herself to the grace of God, became a Christian and lived as a Christian,” he said.

People are convinced that God listens to her and that “she always listens to those in need, just as she did in life,” he said.

Kahnawake embraces Kateri’s spirit

By Carolyn Girard, The Catholic RegisterKAHNAWAKE, QUE. - The small Catholic community of St. Francis Xavier Church, with the St. Lawrence River and sprawling Montreal as its backdrop, has enthusiastically prepared for the canonization of Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha.

Located in Mohawk territory in Kahnawake, the church enshrines the remains of Blessed Kateri, a native woman who found refuge and spiritual renewal in the region where she spent her final days as a Catholic. Her remains lay beneath a marble tomb in the church, entombed primarily to ensure their safety and respect, as someone had previously attempted to steal them many years ago.

Pilgrims can kneel and pray or light a votive candle with Blessed Kateri’s likeness on it. The image is based on an oil-on-canvas painting, housed in a room beyond the gift shop, painted by Jesuit Father Claude Chauchetiere, the pastor of St. Francis Xavier Mission from 1677 to 1688, and a witness at Blessed Kateri’s death.

In a gift shop adjacent to the church, Kahnawake native Ann-Marie Sky talks about the importance of Blessed Kateri’s example not only for herself, but for the survival of the parish.

“For me, it’s her spirituality and her perseverance during the time and after she became Catholic. She was ostracized for that, so her faith really carried her through,” Sky said. Similarly, the parish has had to learn to persevere just to keep the church doors open.

“The church almost had to close a year and a half ago due to finances,” Sky explained. “We were just working our way back up and we got the news that she will be canonized, so now we’re really trying to keep the church afloat.”

For a parish that only sees about 60 regular Mass-goers on Sunday mornings, the annual $25,000 price tag for utilities to heat and use the church has been a challenge. But with great faith and ambitious fundraisers, it has managed to pay the bills. And since the announcement that Kateri would be canonized on Oct. 21, making her the first North American aboriginal saint, the parish has seen nearly three times the number of pilgrims it normally sees. The demand for Kateri merchandise has risen and Sky is trying to stock enough merchandise before Oct. 21, when the mission expects busloads of visitors to join parishioners for a re-broadcast of the canonization in Rome.

The Pope’s Feb. 18 announcement of Kateri’s canonization came as a surprise.

“I couldn’t believe it, because after Brother André was canonized, I didn’t think there would be anybody else from Quebec canonized for another 20 years,” Sky said.

And not only in Quebec, but from the same area, she added. From the church in Kahnawake, the dome of St. Joseph’s Oratory on Mount Royal — the legacy of St. Brother André — is easy to spot across the river on a clear day.

Like Sky, Kahnawake resident Beverly Delormier has been working diligently to prepare for the big day, although Delormier will be spending it in Rome.

“I was there in 1980 with my daughters when she was beatified and never in my wildest dreams did I think that I would go there again for the canonization,” marvelled Delormier. “The day of the beatification everybody had their native dress on, so it was really something spectacular to see.”

For Delormier, Blessed Kateri is an important intercessor.

“It’s all little things, but I believe in the power of prayer.”

Deacon Ron Boyer, Canadian vice-postulator for the canonization of Kateri, says her canonization is long overdue. But more importantly, the canonization brings to light God’s desire to reach the aboriginal people.

“Her first miracle happened about 15 minutes after she died,” Boyer said, referring to the historical accounts of Kateri’s transformation. Kateri had contracted smallpox as a child and was left partially blind and covered with facial scars. Minutes after her death, any trace of her scars vanished and her appearance was described as beautiful.

“Why would God glorify a dead body? Why? Nobody has been able to answer that for me, but I believe He did it to show us that there is a God,” Boyer concludes.

Boyer adds Kateri is also significant for her impact on Christians and non-Christians alike.

“Many non-Catholic aboriginal people are going to Rome to pay homage to Kateri. She was special, a lady of many qualities,” Boyer said. “She is also the empress of ecology and a symbol for the youth.”

As the diocese of Saint-Jean- Longueuil is not immune to the shortage of priests in Canada, St. Francis Xavier has a pastor, Fr. Raymond Esprit, who is present only three days per week. Boyer hopes the canonization and increased traffic might mean a permanent priest in the future.

In the meantime, the canonization has already served to strengthen ties within the Kahnawake community. A committee from the parish has been working with the diocese to prepare for the big day, as well as a thanksgiving Mass to be held at St. Joseph’s Oratory on Nov. 4.

Saint-Jean-Longueuil diocese is sending 200 pilgrims to Rome.

“For the native communities and for the larger community in North America, the canonization is extremely important because of her status as the first native woman of our continent to be recognized as a saint,” said Auxiliary Bishop Louis Dicaire. “We have been surprised by the interest from the general population of our diocese, often among young people 25 to 30 years old. Kateri is providing a source of inspiration.”

Although children do not receive formal Catholic education through the Quebec school system, volunteers at the Shrine say visits from area schools are on the rise and children learn about the woman whose name graces the local hospital, school and nearby island.

(Girard is a freelance writer in Ottawa.)

Boy’s recovery a Kateri miracle

By Eric W. Mauser, Canadian Catholic NewsWhen then five-year-old Jake Finkbonner showed up to play his last basketball game of the season in Ferndale, Wash., he had no idea it would change his life and lead to events that would culminate in the canonization of a saint.

St. Kateri Tekakwitha: a life of faith

By Michael Swan, The Catholic RegisterTwice a refugee. Twice an orphan. An outsider among her own people. Kateri Tekakwitha lived in a time of war, famine, disease and turmoil. She was baptized at 20 and dead at 24 but lived such an extraordinary life of faith, courage and hope that the Church has now invested its hope in her, declaring her the first North American aboriginal saint, patron of ecology and ecologists, of exiles and youth.

St. Peter’s Square will look very different when Pope Benedict XVI declares Blessed Kateri a saint Oct. 21. Hundreds of native North Americans in traditional beads, feathers and blankets, carrying drums and wampum belts, will fill the heart of the Vatican. In the often painful history of the Church’s relationship with the original people of this country, there’s never been a moment quite like this.

“it’s very affirming and definitely gives us a whole new perspective on our sense of belonging in the Church,” said Sr. Kateri Mitchell, executive director of the Kateri Conference National Centre in Great Falls, Montana.

There will be all kinds of attempts to claim Kateri. Canadians will claim her as a native Canadian who lived and died in New France.

“This will be a great day for Canadian Catholics and a deep honour for our country,” said Prime Minister Stephen Harper when plans to make the Lily of the Mohawks a saint were announced in February.

The Jesuits also have a legitimate claim, having begun their efforts to have Kateri declared a saint more than 100 years ago.

“The Jesuits consider her one of theirs,” said Jesuit archivist Fr. Jacques Monet.

It was two 17th-century Jesuits, Fr. Pierre Colonec and Fr. Claude Chauchetiere, who wrote the first biographies of Kateri. Chauchetiere painted a portrait of her a few years after her death. It was the Jesuits who sheltered her at their mission in Sault Ste. Louis in 1677.

Though she is the Lily of the Mohawks, “It’s not going to be just the Mohawks there (at the canonization),” said Ojibway elder Rosella Kinoshameg a week before she was to fly to Rome with a delegation of mostly Mohawk followers of Kateri. Kinoshameg is a member of the Canadian Catholic Aboriginal Council, the official liaison between Canada’s Catholic bishops and aboriginal Catholics.

There are native people from across North America who identify with Kateri.

“She was born in 1656, died in 1680,” said Mitchell. “There wereno countries, no boundaries at that time. We had our own Turtle Island, which is North America. I just consider her a North American indigenous person.”

But once a saint, Kateri is a saint for the entire Church and an example to the whole world.

“It is a recognition by the Catholic Church of the holiness that exists among the native peoples,” said Monet.

There have been at least 300 books published about the life of Kateri, but few take seriously the historical and cultural circumstances of her life in the middle of the 17th century. A second look at Kateri leads to the conclusion that her fervent, mystical embrace of Christ was never a rejection of traditional Mohawk beliefs but rather a fulfilment of them, writes Mohawk historian Darren Bonaparte.

The tragic results of colonization struck Kateri early in her life. The European smallpox virus raged through her community the winter of 1661-1662. It killed her parents and her baby brother, and left her nearly blind with extreme sensitivity to light.

Kateri was born into wars that raged for control of the fur trade. Her Turtle Clan Algonquin mother, Tagascouita, had been captured in a Mohawk raid on Trois-Rivieres in then New France. By this process Tagascouita became Mohawk and was married to a Kenneronkwa, a war chief. She was born in Ossernenon, a village of the Iroquois Confederacy more than 360 kilometres south of Montreal in modern day New York State.

In the aftermath of the smallpox epidemic, Kateri was adopted by her maternal uncle, a chief of the Turtle Clan.

When she was 10 years old the French army launched an expedition into Mohawk territory to put a stop to Mohawk raids against the Huron, who were allies and trading partners with the French. The Mohawks were selling their furs into the Dutch network of trading posts around modern-day Albany and Schenectady, New York. It took the French a couple of tries, but they eventually looted and burned the village where Kateri was living at the time, Kahnawake or “At the Rapids.”

The French victory opened the door for Jesuit missionaries to move into Mohawk villages. The Jesuits learned the Mohawk language and were careful to ensure converts truly embraced the faith of their free will. Most converts were not baptized until near the end of their lives.

The new religion was splitting Mohawk villages. Kateri was in the middle of the split. Her father opposed the French and their religion. Another chief, Kryn the Great Mohawk, took more than 40 people with him to the Christian village of Kahentake near Montreal in 1673, including Kateri’s older sister.

Her adopted father forbade Kateri from going near the missionaries in an attempt to keep what was left of his family and his village together. But the girl knew her mother had been Christian and contact with the Jesuits became almost inevitable. Stuck in the village one day in 1675 with an injury, unable to work the land with the other women, Kateri ran into Fr. Jacques de Lamberville — a new missionary still trying to learn a very foreign language.

Lamberville baptized her with the name Catherine, after Catherine of Siena, Easter Sunday, 1676.

Meanwhile Kateri’s adoptive parents had been arranging a marriage for her. Marriage was the first and most important obligation of every Mohawk girl to her community. Kateri’s refusal to marry could have only shamed her uncle. Her Jesuit biographers report that the entire village turned against young Kateri.

In 1677 Kateri’s sister sent her husband into the Mohawk Valley. At 20 Kateri was off on a perilous journey with her brother-in-law through Lake Champlain and eventually back to the Christian village of Sault Ste. Louis on the shore of the St. Lawrence River.

In her new village, Kateri formed a close bond with an older woman named Kanahstatsi Tekonwatsenhonko, who became like another mother to her. Kateri also made friends with a young widow named Wari Teres Tekaienkwenhtha.

Kanahstatsi and Kateri’s older sister in Sault Ste. Louis began to pressure Kateri to marry, but the younger woman was fascinated by the life and witness of French nuns. The Jesuits argued native converts were too young in the faith to join an order of nuns. Denied that possibility, in 1679, on the Feast of Annunciation, Kateri made a personal vow of perpetual virginity.

Kateri and her friend Wari Teres became central figures in a movement of young women who took up extreme penitential practices in imitation of the Jesuits. Mostly symbolic self-flagellation was a normal practice among Jesuits of the time. The young women took it to extremes, and none more extreme than Kateri.

Kateri was frail, malnourished and tiny. The penitential practices likely took their toll. On Holy Thursday, April 17, 1680, her dying words were, “I love you, Jesus.”

“Then her face suddenly changed,” wrote the Jesuit missionary Cholenec. “It appeared to be smiling and devout and everyone was extremely astonished. We were all admiring her face and we could not have tired ourselves of looking at her.”

The scars that had marked her since her brush with smallpox seemed to disappear.

For many native people, the Holy Father’s declaration of sainthood for Kateri will only bring Rome up to date. Devotion to her has been building for generations among native North Americans who have long thought of her as their saint.

The native-focussed parish in Thunder Bay, Ont., is called Kitchitwa Kateri. Kitchitwa is the Ojibwa word for holy, blessed or sacred. Since there’s no separate word for saint, the parish will continue to be called Kitchitwa Kateri after her canonization, said Jesuit Father Larry Kroker.

Kinoshameg remembers praying for Kateri’s canonization as a school girl in the 1960s. As a young woman she attended Kateri prayer weekends and over the years she’s been to several Tekakwitha conferences in the United States and Canada. For as long as she can remember, Kateri has been part of Catholic native spirituality.

Though many native parishes seem to be dominated by elders, Kinoshameg believes devotion to Kateri will continue among those under the age of 25.

“I would hope young people would see that here is a young woman who has to be strong and be brave — really brave with all this turmoil going around,” she said.

The story of Kateri gives an example of perseverance that can only help young native people, said Kinoshameg.

“(Kateri) has a significant role to play in the future of the Catholic native Church insofar as she’s young,” said Jesuit Father David Schulist, director of the Anishinabe Spiritual Centre near Espanola, Ont.

The next generation needs to see themselves in the Church.

“There is now somebody they can refer to. Their lives are not seen entirely looking or gazing at a Eurocentric kind of faith,” Schulist said.

To get ready for the canonization, Campion College campus minister Stephanie Molloy organized a mini-pilgrimage on Oct. 10 through downtown Regina for 47 inner city students from Sacred Heart Community School. A large percentage of the students are aboriginal. The kids loved it.

“Definitely there’s the link with young people. She’s the patron of ecology and things that young people care about,” said Molloy.

That connection with youth was central to Pope John Paul II’s thinking when he beatified Kateri in 1980. In 2002 he would make her one of the special patrons of World Youth Day in Toronto.

John Robinson, an elder from Toronto’s Native People’s parish, will be one of about 180 native people from Ontario alone in Rome for the canonization. This begins a new chapter, he said.

“A lot of native people in cities and outside of cities are going to look to Kateri as a saint in a special way,” he said. “This is our first native saint and they’re going to have a lot of respect for it.”