From the 1611 arrival of the first Jesuit missionaries on Canadian soil to well after Confederation, Canada’s Jesuit priests and brothers engaged in ministry across Quebec, Ontario and into the West. But for most of the last century, they’ve also looked beyond Canadian borders and taken the Gospel message of faith, peace and justice to marginalized people in distant lands.

Almost 500 years ago, Jesuit founder St. Ignatius Loyola urged St. Francis Xavier to “Go forth and set the world on fire with the love of God,” as St. Francis departed to spread the Gospel in India and Japan. That same message carried the first French missionaries to Canada and today it inspires Canadian Jesuits around the world as they live out the order’s unwavering commitment to social justice through international development.

Today Canadian Jesuits can be found in Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and Europe. They are engaged in missionary work overseen by the Bureau des Missions in Montreal and Canadian Jesuits International in Toronto. The two offices co-ordinate significant international undertakings in the areas of education, pastoral care, social services, community development, agriculture, peace-building and social justice.

Social justice Jesuit-style is for God’s greater glory

By Luc Rinaldi, The Catholic RegisterThe term social justice may seem inseparable today from images of building schools in Africa, defending the rights of the oppressed and lobbying in the corridors of power. The image it likely doesn’t provoke is that of Luigi Taparelli D’Azeglio, the 19th-century Jesuit who coined it.

Social justice, widely used to describe the promotion of human rights and dignity of every person, was introduced in 1840, but only recently has it taken such a large role in both the secular and religious world.

Even the Jesuits, its architects, have only developed a modern understanding of social justice in the last quarter century.

Martin Royackers was first English Canadian Jesuit killed in service

By Catholic Register StaffIn Jamaica they called Fr. Martin Royackers a “roots man.” Around the world, Jesuits and their friends call him a martyr.

He was the first English Canadian Jesuit to be killed on the job.

Royackers was born and died in farming communities. Born Nov. 14, 1959 near Strathroy, Ont., he was killed outside St. Theresa’s parish church in Annotto Bay, Jamaica, June 20, 2001.

Three martyred at China mission

By Catholic Register StaffFr. Prosper Bernard, Fr. Alphonse Dubé and Fr. Armand Lalonde were three of more than 100 Quebec Jesuits who became missionaries in China between 1918 and 1954. They are also three of more than 300 Jesuits worldwide martyred in the 20th century.

The involvement of Quebec Jesuits in China started with an invitation from France’s Jesuits. A few helping hands were sent from Quebec to Shanghai. But their numbers quickly grew as Quebeckers embraced the mission to China. Jesuit missionaries were supported by Quebeckers through the Holy Childhood Association and parish-based missionary weeks.

“There was incredible international awareness (in Quebec),” said Jesuit historian Fr. John Meehan of Campion College in Regina.

Arts are a tool towards the Jesuit mission goal

By Fr. Erik Oland S.J., Catholic Register SpecialHaving abandoned a career in classical music for the Jesuit novitiate, I was quite surprised in the early days of my Jesuit life to discover it was commonly held that Jesuits and the arts don’t get along.

A stormy relationship with music and the arts had not been my experience as a young music student. I learned in music history classes that such great composers as Palestrina, Victoria, Carissimi and Charpentier had been in the employ of Jesuit institutions. Art history classes taught me of the close relationship between the Society of Jesus and such artistic greats as Bernini and Rubens.

Where did this idea come from?

In reality, the proverbial “Jesuits don’t sing” is based on a misunderstanding of the society’s dispensation from reciting the Divine Office in common. That is, because Jesuits are a religious order that ministers in the world Jesuits praying the liturgy of the hours together has not been part of our tradition. Ignatius Loyola saw very early on it would be counterproductive to expect each Jesuit to return to his community a number of times a day to pray the office.

The Jesuit Relations opened up the New World to Europe

By Michael Swan, The Catholic RegisterThe most popular books in France in the 17th century were written in Canada. The Jesuit Relations told the story of brave and brilliant missionaries who stepped into an unimagined, fantastic world, learned its languages, spoke to its people about God and heroically endured incredible hardships.

From 1632 to 1664, edited collections of letters from Jesuit missionaries to their provincial superiors were published annually in book form. The letters recounted almost day-by-day the activities of Jesuits in New France, their observations concerning Aboriginals and the challenges they faced in the vast colony.

The books inspired a wave of immigration into the colony and raised the equivalent of millions of dollars from private donors and the royal court in Paris. The books formed Europe’s first ideas about the New World — both positive and negative — and encouraged a new, scientific mindset that came to define the Enlightenment.

Finding Jesus through Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises

By Fr. Gilles Mongeau, S.J., Catholic Register SpecialI was 21 years old and I had come to the Jesuit novitiate in Guelph, Ont., for all the wrong reasons. Barely four months into the novitiate, I was ready to pack my bags and go home. But the novice master wisely said: “Why don’t you wait until the Spiritual Exercises in January? See what God has to say about all this.”

The little text of the Spiritual Exercises — formally approved by Pope Paul III in 1548 after many years of crafting and recrafting by St. Ignatius Loyola — proposes a spiritual journey through the mysteries of salvation and Christ’s life. By imagining themselves into the life, death and resurrection of Jesus, St. Ignatius believed retreatants would become free of all disordered attachments, “so that rid of them one might seek and find the divine will with regard to the disposing of one’s life for salvation.”

The Exercises can be made by anyone. St. Ignatius was a lay man when he first conceived the Spiritual Exercises and lay people have been making Ignatian retreats ever since. But they occupy a central role in the life and spiritual development of every Jesuit.

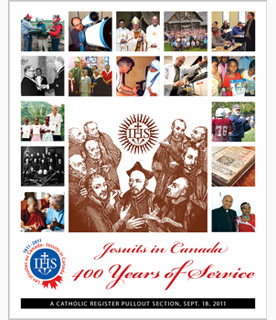

Exhibit unearths gems from Jesuits’ history

By Carolyn Girard, Catholic Register SpecialMONTREAL - The Archive of the Jesuits in Canada has created an exhibition to help tell the extensive 400-year tale of the first order of priests to extensively explore and evangelize the New World.

It’s a display that has made its way to Notre-Dame-de-la-Présentation Church in Shawinigan, Que., a parish getting in touch with its Jesuit past.

The exhibition, on loan from the Jesuits’ Montreal archive, is an exclusive collection that has only appeared in one other location, at the Port Royal National Historic Site in Nova Scotia, where the Jesuits began their year of celebration of 400 years in Canada this past spring.

“The exhibition brings us great pride on two levels,” said Louise Bellemare, a spokesperson for the city of Shawinigan.

The formation process for a Jesuit is laborious, lengthy — up to 15 years

By Catholic Register StaffJesuit formation is famously tough, thorough and long. There are distinct stages to Jesuit formation, which can take 15 years or more to complete.

While there is no such thing as a postulancy prior to the novitiate for Jesuits, you can’t just walk into a novitiate. Once a young man expresses an interest in trying out Jesuit life he will usually be assigned a spiritual director. It may be months, a year or even longer before he is admitted to the novitiate.

As in most Catholic religious orders, Jesuits start out as novices. While novices in most other orders take vows after one year, the Jesuit novitiate lasts two years. After first vows, a Jesuit is assigned to “first studies.” Classically, these consisted of Greek and Latin literature. These days they are likely to include modern languages, philosophy and other studies that may lead to a bachelors or masters degree, depending on the education the young Jesuit had before entering the order. This period usually lasts two years.

Experiencing God in ecology

By Luc Rinaldi, The Catholic RegisterOn the 400th anniversary of their arrival to Canada, the Jesuits are thinking 500 years ahead.

The Old Growth Forest Project, an initiative of the Ignatius Jesuit Centre of Guelph, Ont., is a replanting effort that, over half a millennium, will restore 100 acres of clear-cut land north of Guelph into the type of forest that greeted the first Jesuits in the area 160 years ago.

The project is intended to help promote spiritual development and ecological education in keeping with the spiritual values of Jesuit founder St. Ignatius Loyola. It is just one example of how Jesuit social justice is being expressed through ecology.

“We understand that the root of the ecological crisis is a spiritual crisis,” said Fr. Jim Profit, S.J., executive director of the centre. “It’s important to have people of faith address these issues from a spiritual perspective.”

Jesuit heroes through the years

By Catholic Register StaffIgnatius of Loyola: a saint ‘inclined toward love’

IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA

Dec. 24, 1491 - July 31, 1556

As he lay on his supposed deathbed in 1521, it would be hard to believe Ignatius of Loyola would become the founder of the Society of Jesus. A rash, worldly and contentious young officer in the Spanish army, he paid little attention to matters of faith. It wasn’t until he was struck with a cannon ball and told to prepare for death that Ignatius began his turn to God.

Left with only a book on the lives of the saints after his health took an unexpected turn for the better, Ignatius was inspired to model his life after theirs. By the time he had fully healed — though he spent the rest of his life with a limp — he had decided he wanted to go to Jerusalem and live where Jesus had.

Along his pilgrimage, Ignatius stopped in a cave near Manresa, a town in Spain, where he planned to spend a few days, but ended up staying for 10 months. It was here that Ignatius had a vision, which he never revealed, that led him to see God in all things. Here, he also undertook penances and fasts, trying to imitate — and even outdo — those of the saints. This extreme fasting would permanently damage his stomach.

After passing through Barcelona and Rome, Ignatius eventually arrived in the Holy Land only to be immediately sent away because the Turk-ruled Jerusalem was too dangerous for Catholics at the time.

Over the next several years, Ignatius studied in various European schools and universities, though his desire to go to the Holy Land never dwindled. While at the University of Paris, he met and began to influence Francis Xavier, Peter Faber and a few other students, directing them all through what is known today as the Spiritual Exercises. Together, Ignatius and six fellow students decided that if they couldn’t go to the Holy Land, they would travel to Rome and put themselves at the disposal of the pope.

By 1539, Ignatius had been ordained to the priesthood. Realizing that it was likely he’d never be able to travel to Jerusalem, he formed the Society of Jesus with six of his companions, with the approval of Pope Paul III.

Ignatius was unanimously voted the superior of the Society — twice. After the first vote, he begged his fellow members to pray, reconsider and vote again after a few days. They did, only to yield the same result. Though reluctant, Ignatius accepted the responsibility when his confessor convinced him it was God’s will.

As superior, Ignatius remained in his office in Rome, though his real passion was to teach children and direct adults through the Spiritual Excercises. Over the next 15 years, he wrote almost 7,000 letters to colleagues in the Jesuit order, which grew to include nearly 1,000 members by the time of his death.

On July 31, 1556, Ignatius died after an increasingly taxing struggle with the stomach problems he had developed when he was younger.

He was beatified on July 27, 1609, and canonized by Pope Gregory XV on March 12, 1622, together with St. Francis Xavier.

Though often portrayed as a stern, unemotional soldier, Ignatius was known among the members of the Society as a loving superior.

One of Ignatius’ closest companions, Luis Goncalves de Camara, wrote, “He was always rather inclined toward love; moreover, he seemed all love, and because of that he was universally loved by all.

There was no one in the Society who did not have great love for him and did not consider himself much loved by him.”

Brébeuf’s heavy load

JEAN DE BRÉBEUF

March 25, 1593 - March 16, 1649

It was perhaps one of the most gruesome of all martyrdoms — bound to a stake, his fingernails were torn from his fingers, his feet severed from his legs and his tongue cut out. But throughout the entire ordeal, Jean de Brébeuf never cried out.

Once he had died, his Iroquois captors ate his heart and drank his blood in hope that they might gain his courage. For another 3,000 indigenous Canadians, however, Brébeuf’s valour inspired an entirely different reaction: a conversion to Christianity.

The scale of conversions following Brébeuf’s death is a far cry from his first years among the Huron, when his evangelical efforts met little success.

The French-born Jesuit first travelled to New France in 1625, three years after his ordination to the priesthood. He was chosen to work in the Huron country (near modern day Midland, Ont.) because of his talent for languages. In his time with the Huron, he would author the first Huron dictionary as well as write the Huron Carol, an indigenous understanding of the nativity still used today.

Though he returned to France in 1629 before converting even a single Huron, Brébeuf soon returned to Canada and was tasked to found and organize a formal mission, which the Jesuits hoped would serve as a prototype for future missions among indigenous peoples.

But in 1634, only a year after this mission began, all hopes of an ideal mission disappeared. Smallpox and dysentery epidemics provoked threats to Brébeuf and his companions’ lives, beginning a pattern of illnesses and subsequent backlash against the Jesuits. The Huron — not entirely mistaken — blamed the Europeans for bringing plagues to their homes. In 1639, after another epidemic, the Hurons tore crosses down, vandalized chapels and even beat Brébeuf and other Jesuits.

By 1641, 15 years after Brébeuf’s arrival in Huron country, there were still only 60 converts and the original Huron mission and its residence had been abandoned. But by 1644, another mission had been established. At this time, the French Jesuits proved an important ally for the Huron, who were undergoing regular attacks at the hands of the Iroquois.

Brébeuf had by now earned the title of Echon among the Huron, meaning “he who carries a heavy load.” But it was a burden he carried with joy, commitment and piety. Throughout his writings, he established his willingness to die for Christ.

In 1649, that willingness was fulfilled. In subsequent attacks on the towns of Saint-Ignace and Saint-Louis, where Brébeuf worked, the Iroquois captured and martyred him.

Brébeuf, “the giant of the Huron missions,” a title earned for both his physical and spiritual grandeur, was canonized in 1930 by Pope Pius XI.

“Your life hangs by a thread. Of calamities you are the cause — the scarcity of game, a fire, famine or an epidemic… you are the reasons, and at any time a savage may burn your cabin down or split your head,” Brébeuf wrote to would-be missionaries. “ ‘Wherein the gain,’ you ask? There is no gain but this — that what you suffer shall be of God.”

Obedience the rule for martyred Noël Chabanel

NOËL CHABANEL

Feb. 2, 1613 - Dec. 8, 1649

Noël Chabanel could never grasp the Huron language. He hated their food and he never became comfortable with the missionary lifestyle. He loathed Huron rituals and customs, and, to add to it all, he was going through a period of spiritual dryness during his time as a missionary.

So he might be the last person you’d expect to make a vow before the Blessed Sacrament to never leave the Huron mission.

Chabanel, a French-born Jesuit, didn’t always have such distaste for life among the indigenous of Canada. In fact, after being ordained in 1641 and serving as a professor in Jesuit colleges in France for several years, he felt a particular call to be a missionary. In 1643, after studying the Algonquin language, Chabanel sailed to New France.

Accompanied by fellow Jesuit Charles Garnier, Chabanel was appointed to Sainte-Marie, where he worked among the Hurons until 1649. In December of that year, he was working at the mission in the village of Saint-Jean when it was attacked and its inhabitants massacred by the Iroquois. Though Chabanel survived the Iroquois attack, he was murdered by an apostate Huron as he led other survivors to safety. The Huron murderer admitted that the act was out of a hatred for the faith.

In his death, Chabanel stayed loyal to the vow he had made years earlier.

“I am going where obedience calls me,” he said to his superiors on the day he died. Whatever mission he was called to, he said, “I must serve God faithfully until death.”

Antoine Daniel’s indomitable courage shone through in adversity

ANTOINE DANIEL

May 27, 1601 - July 4, 1648

In 1626, a young Huron boy named Amantacha came to France, anxious to learn about Christianity. Little did he know that he wouldn’t only be inspired, but also inspire.

This young Huron was placed under the instruction of Antoine Daniel, a French Jesuit who had been ordained five years prior. Educating the boy, Daniel felt more and more called to serve as a missionary. In 1632, Daniel followed that call and departed for New France, where he was assigned to the Huron mission with Jean de Brébeuf.

While among the Huron, Daniel taught the children prayers with remarkable kindness and gentleness. Because of his talent with the young, Daniel was chosen to establish a Christian school for Huron boys. Two years of tireless effort, however, would prove that the Huron were not receptive to European schooling and the school was closed.

Daniel returned to active missionary life for the next 10 years until, in 1648, Iroquois attacked a village in which he was celebrating Mass. Hearing the battle cries of the enemy, Daniel quickly baptized and absolved many of the faithful and told them to flee.

But Daniel didn’t take his own advice. Instead, he charged the enemy with cross in hand, hoping to create a diversion for the Hurons. He was successful, but at the cost of his life. After being riddled with arrows, his body was thrown into the chapel, which was set ablaze.

Daniel’s superior wrote of him, “(He was) a truly remarkable man, humble, obedient, united with God, of never failing patience and indomitable courage in adversity.”

Garnier’s heart burned with the fire of the love of God

CHARLES GARNIER

May 25, 1606 - Dec. 7, 1649

While Jean de Brébeuf was the “lion” of the Huron mission, Charles Garnier was known as the “lamb.” But he didn’t let this title downplay his zealous devotion to converting souls.

In fact, if Garnier weren’t so determined, he probably would have never been a missionary at all. In order to travel to Canada, he required the consent of his father, the secretary to King Henri III of France. For a year, he couldn’t convince his father to let him go, but his consistent pleading eventually trumped his father’s reservations, and in 1636, two years after his ordination, Garnier sailed to New France.

Garnier’s arrival in Huron country was accompanied by a drought-ending rainfall, earning him the name Ouracha among the Huron, meaning “rain-giver.” Though well liked by the Huron, Garnier had the same difficulties as the other Jesuits in converting the Huron people in large numbers — only 100 by 1638, half of whom had died.

Garnier remained in Huron country for 11 more years before being martyred at the hands of the Iroquois. After being shot and left to die, Garnier made one last act of charity, dragging himself along the ground to absolve a dying Huron. In the process, he was tomahawked and died.

Fr. Paul Ragueneau, a Jesuit superior, describes Garnier’s last moments in the Jesuit Relations.

“In his zeal he was everywhere at once, now giving absolution to the Christians he met, now running from one blazing cabin to another to baptize, in the very midst of flames, the children, the sick and the catechumens. His own heart burned with no other fire than that of the love of God.”

René Goupil was the first to be martyred

RENÉ GOUPIL

May 15, 1608 - Sept. 23 1642

Deafness prevented René Goupil from entering the Society of Jesus, but it didn’t prevent him from following his call to be a missionary.

Goupil, a young French surgeon, travelled to New France with the Jesuits in 1640 as a donné, a “given man,” a lay volunteer working without pay. Because of his medical skills, Goupil was entrusted with the care of the sick in a Quebec hospital for his first two years in New France.

In 1642, Goupil set out by boat for Huron country with Jesuit Isaac Jogues and a group of Huron. They, however, were intercepted and captured by the Iroquois, who tore the nails from their fingers and beat them before forcing them on a 13-day journey. Jogues offered Goupil many chances to escape, but he refused, saying his suffering was God’s will and that he couldn’t abandon Jogues and the Hurons, whom he tended to during their trek.

Even among his enemies, Goupil strove to evangelize. He was seen teaching a group of indigenous children how to make the sign of the cross, for which he would be murdered. In September of 1642, he was tomahawked and became the first of the eight Canadian martyrs.

Shortly after Goupil’s death, Jogues — who had allowed Goupil to make his vows as a Jesuit — wrote an account of his time with the young man.

“For him it was a question of seeing our Lord in each patient. And thus he left a sweet odour of goodness and of other virtues in that place where his memory is still held in veneration.”

Isaac Jogues, the ‘living martyr’

ISAAC JOGUES

Jan. 10, 1607 - Oct. 18, 1646

On a cold January morning in 1644, a poor priest from New France presented himself at a Jesuit residence in France. He was beaten and bruised, missing fingers and disfigured beyond recognition. After taking him in, the pastor at the residence asked the priest if he had any news of Isaac Jogues, a Jesuit missionary that had been captured in New France.

“He is at liberty,” the man said, “and it is he, Reverend Father, who speaks to you.”

Jogues, a “living martyr,” had managed with the help of the Dutch to escape his Iroquois captors and return to France.

The fifth of nine children in a family of lawyers and merchants, Jogues was a teacher before leaving for New France after his ordination in 1636. While escorting a convoy during his mission, Jogues was attacked and taken prisoner. It was only after countless beatings and witnessing the martyrdom of donné René Goupil that Jogues fled to France, but he wouldn’t stay long. Jogues’ dedication to the mission led him back to New France in the same year he arrived in his home country.

In late 1646, Jogues decided he would stay the winter with the Hurons, but his earthly journey wouldn’t last that long. Mohawks attacked his small group of travellers upon their arrival, killing Jogues with a tomahawk to the head.

Martyrdom was a tragic but not unexpected end to Jogues’ life. He wrote, “It must be that my body suffer the fire of Earth, in order to deliver those poor souls from the flames of Hell; it must die a transient death, in order to procure for them an eternal life.”

Salvation more dear than life Lalemant

GABRIEL LALEMANT

Oct. 3, 1610 - Mar. 17, 1649

Gabriel Lalemant spent only six months with the Hurons in Canada, but his sacrifice for them was no less than any of the other martyrs.

The nephew of two Jesuit missionaries, the priesthood seemed like a natural path for Lalemant. While his desire was to follow the example of his uncles, Lalemant’s frail stature prevented him from becoming a missionary for eight years. During that time, he was ordained and taught in Jesuit colleges.

In 1646, however, Lalemant’s insistence and piety overcame the physical obstacles barring him from missioning to New France. After two years of ministering in Quebec, Lalemant travelled to Huron country. He proved to be an excellent missionary and skilled with the Huron language, for which he was assigned a spot alongside Jean de Brébeuf.

An Iroquois attack on the town of Saint-Ignace where Brébeuf and Lalemant were staying, however, proved that their work together would last only a short time. Upon the attack, the two quickly travelled to the nearby settlement of Saint-Louis, where they warned the Hurons of the coming Iroquois. The men prepared for battle, the women and children fled and Brébeuf and Lalemant baptized, confessed and absolved the Christians in the town.

Inevitably, Brébeuf and Lalemant were captured. They suffered similar fates, having their nails ripped from their fingers and flesh torn from their burnt bodies, bound to a stake. Lalemant’s torturous martyrdom lasted an entire night, until the Iroquois killed him in the morning.

Of Brébeuf and Lalemant, Jesuit superior Fr. Paul Ragueneau wrote, “The salvation of their flock was dearer to them than life itself.”

De La Lande had a desire to serve

JEAN DE LA LANDE

d. Oct. 18, 1646

The first time that many of the Jesuit missionaries in New France heard the name Jean de La Lande was upon news of his death.

Little is known about La Lande, a young donné, or “given man,” who came to New France around 1642 and worked at the Jesuit residence in Trois-Rivières. With other lay volunteers, he humbly worked the less glorified jobs of the mission, as a cook, fisherman, farmer or carpenter, obligated by nothing more than his own desire to serve.

In September of 1646, La Lande accompanied Isaac Jogues as he set out with a plan to stay the winter with the indigenous people to help maintain peaceful relations. The two were accompanied by only a few Huron, all but one of whom abandoned the Jesuits when they realized the danger of the journey.

While the trip proved to be safe and successful, their arrival in Mohawk territory — as supposed peace ambassadors — was not welcome.

They were beaten, robbed and stripped before a group of Mohawks tomahawked them.

The news of these two martyrs didn’t reach New France until more than half a year later, in June 1647. While much attention was paid to Jogues, a well-known Jesuit priest of the mission, La Lande, a lesser-known name, was not overlooked.

“One must not forget the young Frenchman who was slain with the father,” read the Jesuit Relations.

“Jean de la Lande, who though he foresaw the same danger, had courageously exposed himself to it, hoping for no reward but Paradise.”

Lonergan’s influence still spreading

BERNARD LONERGAN

Dec. 17, 1904 - Nov. 26, 1984

In Jesuit Father Bernard Lonergan, the Society of Jesus lays claim to a man that many modern thinkers regard as the most influential philosopher of the 20th century.

Since his death in 1984, Lonergan’s school of thought has rippled worldwide, and Lonergan educational and research centres can be found anywhere from Canada to the Philippines, from the United States to Australia — extending even beyond the reach of his 43-year teaching and writing career, which included positions at Regis College in Toronto, Harvard University, Boston College and the Gregorian University in Rome.

“(Lonergan), with that boldness characteristic of genius… set out to do for the 20th century what Aquinas could not do for the 13th: provide an ‘understanding of understanding,’ ” read an issue of Newsweek magazine.

Critical realism, Lonergan’s school of thought, sets out to discover “how to come about understanding Christian doctrine in a way that’s authentic,” said Fr. Gordon Rixon, S.J., director of the Lonergan Research Institute at Toronto’s Regis College.

By Rixon’s account, Lonergan succeeded in finding that authenticity he was searching for.

“What grabbed me — and I think this is often the case — is the people that I met who were studying Lonergan’s thought seemed to be authentic people,” said Rixon of his introduction to Lonergan’s philosophy. “They were seriously concerned with understanding truth, goodness and beauty.”

These concerns were shared by Lonergan, whose ideas are best shared through his magnum opus, Insight: A Study of Human Understanding, and the subsequent Method in Theology. In these works, Lonergan develops what would become one of his most recognized ideas, the Generalized Empirical Method.

“Just as you formulate a hypothesis about how water boils, you can formulate a hypothesis about how humans understand each other,” said Rixon, explaining the method.

The method, loosely defined as scientific method for the humanities and social sciences, stretches across a broad array of fields, from economics to philosophy and theology. The universality of this approach is part of why Lonergan’s work is so celebrated, said Rixon.

“Whether you’re a scientist, a doctor, a lawyer, a journalist… in all those different fields, you have a mind and you’re using it,” he said. “If you have awareness and self-freedom, you’re better at your profession… It helps (people) ground their profession in their spiritual life.”

It’s an ambition that Rixon and the Lonergan Research Institute — along with dozens more institutions around the world — think is worth promoting.

The Institute is dedicated to preserving, promoting, developing and implementing the thought of Lonergan. Through international seminars, lectures, publishings and scholarly work, the Institute and others like it keep his school of thought alive and well. Rixon and the institute are currently publishing an ongoing series of Lonergan’s works.

Underlying all those works, Rixon added, is a deep Jesuit spirituality rooted in the “self-transcendent” nature of St. Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises.

“Ignatius has a thing about seeing God in all things,” said Rixon. “And Lonergan helps people do that.”

Fr. Lafitau had great respect for New World’s native inhabitants

JOSEPH-FRANÇOIS LAFITAU

Jan. 1, 1681 - July 3, 1746

While many of the first Jesuit missionaries were appalled by the traditions and practices of the indigenous people in New France, Joseph-François Lafitau had only an insatiable curiosity for them.

Lafitau, a French-born Jesuit who entered the Society of Jesus at 15, was sent to Canada in 1711 and worked among the Iroquois in Sault Saint-Louis. A keen observer, he studied the Iroquois customs and language tirelessly.

But the natives weren’t merely Lafitau’s subjects. Unlike some of the Jesuits who had gone before him, Lafitau interacted with the Iroquois on a deeply human level, showing a sense of respect that many of the natives hadn’t come to expect.

Lafitau’s observant eye also played a part in him becoming the first missionary to discover ginseng in New France, which, at that time, was worth three times more than silver because of its medicinal power.

Lafitau is best remembered, however, not for this discovery, but for a book he wrote in 1724 comparing natives to the early civilizations of Europe.

Lafitau’s respect for the natives eventually led him back to France, where he pleaded in court to stop the selling of brandy to natives, and also to request the relocation of the Iroquois settlement to more fertile lands. Apart from a year-long trip back to the mission in 1728, Lafitau stayed in France as mission procurator until his death.

“In (Lafitau)’s view the savages of the New World were men, the Iroquois were people in their own right, and their customary ways were worthy of study,” read one biography. “This was a new kind of primitivism that would transform generic savages into specific Indians.”

Le Jeune’s journals were the first Jesuit Relations

PAUL LE JEUNE

July 1591 - Aug. 7, 1664

Paul Le Jeune wasn’t born into the Catholic faith, he didn’t feel particularly called to the missions in Canada and he never intended his habit of journalling to amount to much.

So even after he converted to Catholicism at age 16, it would be hard to predict that Le Jeune would become the superior general of the Canadian Jesuits, the first editor of the Relations and regarded as the founder of the Jesuit mission.

Ordained in 1624, Le Jeune spent eight years studying and teaching before being appointed to sail to Canada. As one of the first missionaries to arrive, his ministry served as a precedent for future Jesuits. Le Jeune recognized that a native sedentary lifestyle, the construction of schools and hospitals, as well as formal documentation of native languages would help to make the mission more effective.

Le Jeune wrote and sent journals back to France on his ideas and experiences. Over time, they became formalized and are now known as the first editions of the Jesuit Relations.

Le Jeune also set in motion a ministry for African slaves in colonized Quebec. His work had a part in inspiring the Code Noir, a document passed by King Louis XIV of

France, which among other things, guaranteed access to baptism for slaves.

After returning to France in 1649, Le Jeune served as mission procurator for many years.

“I thought nothing of coming to Canada when I was sent here,” wrote Le Jeune. “But I may say that even if I had had an aversion to this country, seeing what I have already seen, I should be touched, had I a heart of bronze.”

Fr. Potier was the first pastor of Windsor’s Assumption parish

PIERRE-PHILIPPE POTIER

Apr. 21 1708 - July 16, 1781

Though Pierre-Philippe Potier sailed to Canada in 1743 aboard the French king’s 52-cannon gunship, he came to help — not hurt — the natives of New France.

Potier began his time in Canada at the Lorette mission in Quebec, where he spent eight months learning the Huron language before travelling to the Huron mission at the mouth of the Detroit River. Two years after his arrival there, he became the mission superior of the settlement. Potier took the trouble as superior to document the name of the leader in each of the settlement’s 33 lodges, along with the number of people they held and those who were baptized.

Not even through his first year of being superior, however, Potier’s records were rendered useless as his settlement was destroyed by a native war party. But he had no hesitation in re-establishing the settlement. When a new mission was built in modern-day Windsor, Potier took responsibility for both the Hurons and the French settlers along the river.

Potier became the first pastor of Notre-Dame-de-l’Assomption in Windsor in 1767, the year it was founded, and continued that ministry until his death. Potier was remembered after his passing for a collection of 22 books he had written on topics from philosophy to religion to the sciences, along with an extensive Huron dictionary.

“Because of its early date and its abundant information,” one biography said of the dictionary, “this document has proven of inestimable value for the study of the history of language in Quebec.”

Fr. Martin was integral to cataloguing Jesuit history

FÉLIX MARTIN

Oct. 4, 1804 - Nov. 25, 1886

Much of what today’s Catholics know about the early Canadian Jesuits is owed to Félix Martin, a Jesuit missionary who set sail for the New World in 1842.

The founder of Collège Sainte-Marie in Montreal, Martin collected and translated documents from the early missions, including issues of the Relations, maps and other documents. His keen interest in history and biography led him to write a number of books about the Canadian Martyrs, only one of his many projects.

In 1856, Martin was given the task of uncovering the traces of old Huron settlements in New France. He spent the following year in Paris and Rome searching through archives, hunting for documents on Canadian history. Upon his return to New France in 1858, he became a founding member of the Société Historique de Montreal.

Through all his time archiving and researching, Martin also served as the superior of the Jesuits in Canada East, and later, the superior of the Jesuit residence in Quebec. In 1868, he became superior of the Collège de l’Immaculée-Conception.

But Martin’s numerous positions and archival efforts are not the only evidence of his time in New France. An architect, Martin was also responsible for the design of several churches and colleges, including St. Patrick’s Basilica in Montreal, still standing today.

In 1880, Martin retired to Paris, where he stayed until his death six years later.

Though Martin’s name may not be known by many today, it was his work that allowed for the names of other Jesuits to be so well known and celebrated.

Arthur Jones was key in deciphering Martin’s work

ARTHUR E. JONES

Nov. 17, 1838 - Jan. 19, 1918

Arthur E. Jones spent the summers of his childhood canoeing around the Thousand Islands at the eastern end of Lake Ontario, just like Jesuit missionaries had done 200 years before him. It was only fitting, then, that Jones would himself become a member of the Society of Jesus and an expert on the lives of Jesuits who had walked before him.

Jones entered the novitiate at 19 and was ordained in 1873, but it was in 1882 that he began his life’s greatest work. Placed in charge of the rich archives of Collège Sainte-Marie assembled by Jesuit Félix Martin, he was tasked with sorting through, reading and deciphering old Jesuit documents.

In his time there, Jones identified the authorship of many important manuscripts, including one relating to the death of 18th-century Jesuits Jean Aulneau and J.B. de La Vérendrye. As result of his work with the document, the remains of the two Jesuits were found in 1908. He also worked with 16th-century Jesuit maps, often searching out the sites of early Blackrobe missions himself in his travels.

Jones’ work, including a collection of newspaper articles about his work and a book, Old Huronia, which outlined his travel and discoveries, were not overlooked. He was the first Jesuit to be elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Jones died a month after the 60th anniversary of his ordination, where he affirmed his never-failing enthusiasm for the work he did.

“I have never regretted a day of it,” he said.

Fr. Baxter was known as the ‘Apostle of the Railway Builders’

RICHARD BAXTER

March 28, 1821 - May 8, 1904

In 1845, the Canadian Jesuits were almost exclusively French. That, however, didn’t stop English-born Richard Baxter from joining their ranks.

The eldest of four children, Baxter emigrated to Barrie, Ont., at a young age. He was ordained in 1854 after two years at the Jesuit novitiate in Montreal, three years of teaching at St. Francis Xavier School in New York and another four years of theology at St. John’s College, later renamed Fordham University. The bilingual Jesuit was then posted to various locations across northern Ontario — leaving his mark at every stop along the way, founding parishes in the towns of White River, Schreiber and modern-day Thunder Bay.

His most important apostolate, however, was his ministry to the construction crews of the Canadian Pacific Railway around Lake Superior. Here, he developed a legacy for his leadership, his rugged physique and zeal even amidst simple, lowly conditions of living. He was universally respected and admired for his temperament and compassion, becoming known among the crew as the Apostle of the Railway Builders.

He was expected to retire in 1893 at age 72, but instead decided to serve as a pastor in Sault Ste. Marie, where he remained until his health simply wouldn’t let him continue any longer. In 1901, Baxter moved to Montreal where he remained until his death.

While Baxter’s life ended in 1904, he would be remembered for many years to come for his work. In 1975, the centennial year of St. Andrew’s Catholic Church, the Thunder Bay parish that Baxter had a hand in founding, the Ontario Heritage Foundation created a plaque honouring Baxter and his multitude of accomplishments.

A mischievous prankster and a serious scholar

DAVID M. STANLEY

Oct. 17, 1914 - Dec. 30, 1996

The young and mischievous David M. Stanley was probably best remembered among his peers for his outrageous pranks while in the seminary. But now, his life’s legacy is more likely to include his extensive work as scriptural scholar, author and educator.

Stanley, a Chatham, Ont., native, was ordained in 1946 before beginning a far-reaching teaching career that would last four decades. In this time, he taught at three different Toronto institutions, including Regis College where he was dean for three years, as well as at the University of Iowa, the University of San Francisco and the Gregorian University in Rome.

Stanley’s impressive resume also included a variety of memberships in Catholic groups and commissions, presidency of the Catholic Biblical Association of America, and honorary doctorates galore. A specialist in the New Testament, Stanley wrote nine major books. Late in life, Stanley became a tireless promoter of St. Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises.

While Stanley’s pranks may not have continued through his entire priesthood, his engaging personality did. He was recognized for a lively warmth but also for being opinionated and even rash at times.

Stanley was placed at the Jesuit Infirmary in Guelph in 1991, where he remained until his death.

“When the history of the American Catholic biblical movement is written, (Stanley)’s name must be given a place of honour,” wrote a fellow biblical scholar. “With considerable courage he defended ideas which at that time were considered dangerous but now are taken for granted even in elementary teaching.”

Fr. Mackey honoured as a ‘Beloved Son of Bhutan’

WILLIAM J. MACKEY

Aug. 19, 1915 - Oct. 18, 1995

When he turned down a shot at a professional hockey career to join the Society of Jesus, William J. Mackey could never have foreseen the life that lay ahead of him.

For more than 15 years after his ordination in 1945, Mackey served in India as headmaster and pastor among other jobs at two schools. Here, Mackey taught the future king of Bhutan — but it was the current king who was most interested in Mackey’s work as an educator. The king invited him to develop an education system in Bhutan, which, at that point, had no towns or cities and consisted only of small clusters of families.

Mackey founded the country’s first high school and was responsible for recruiting its students as well. In doing so, he travelled the country’s mountainous terrain by foot, horse and motorcycle.

Mackey also founded the nation’s first junior college, followed by another high school where he remained for 10 years. He later worked for the country’s ministry of education, again travelling the nation, even at age 70.

Mackey died of blood poisoning at age 80, but not before he was declared a “Beloved Son of Bhutan” and granted citizenship by the king, the only missionary to have ever received this recognition.

A writing from a close colleague of the Jesuit read, “To watch Fr. Mackey light his Buddhist temple candles and say Mass each morning in his small Bhutanese house is an affirmation of all that is good in the human spirit.”

The Spiritual Exercises were a moving target for Fr. English

JOHN J.C. ENGLISH

Feb. 7, 1924 - June 9, 2004

For John J.C. English, the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola were like a “Shakespearean play… always being interpreted and reinterpreted, changing to different cultures and times.”

And it was English himself who provided the interpretation for his times.

A Regina native, English was ordained a Jesuit in 1961 after enlisting with the Royal Canadian Air Force for a time and studying sciences at the University of British Columbia. While the nine books English wrote on the Spiritual Exercises earned him a trusted name in Ignatian spirituality, it was his work as novice master in Guelph, Ont., that made him known as a compassionate and innovative spiritual leader.

In Guelph — where he worked for 30 years — English developed a new method of spiritual direction. He interviewed novices twice daily and was known for running creative spiritual “experiments” with them.

Later in his life, English became involved with the Christian Life Community, a collective of small groups of lay people seeking deeper spiritual lives with a focus on finding God in all things — a concept right in line with the Spiritual Exercises.

In 2001, English was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He died three years later in Winnipeg, where he had spent the later portion of his life as the superior of the Jesuit community.

Remembered just as well as his spiritual and academic contributions to the Jesuit community were his “easy manner, an infectious laugh and a delightful sense of humour,” a Jesuit biography reads.

“He lived with the consistency of the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola, which he had spent so much of his life promoting.”