The College of Cardinals extensively discussed corruption and mismanagement sensationally documented in the 2012 “VatiLeaks” of confidential correspondence, which were also the subject of a detailed report that Pope Benedict XVI designated exclusively for the eyes of his successor.

The new Pope has already given signs of his intention to reform. According to his personal notes for his pre-conclave speech to fellow cardinals, subsequently published with his permission, then-Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio denounced the “self-referentiality” of a Church “living within herself, of herself, for herself.” Although his main target seems to have been a “theological narcissism” that saps evangelical zeal, his words were also an implicit rebuke to the inward-looking mindset of a pre-modern royal court, which still characterizes the Vatican in the 21st century.

Since his election, Pope Francis’ many gestures of humility and accessibility — such as praying at the back of the chapel where he celebrated Mass for Vatican maintenance workers — not only underscore his avowed desire that the Church be close to the poorest and least powerful, they also set an example for higher-ranking officials.

His decision to live in the Vatican guesthouse rather than in the Apostolic Palace also says a lot about his approach to management. This Pope will not be a prisoner of any gatekeepers and will be free to hear a wide range of his collaborators’ voices.

As he moves beyond words and gestures to the stage of substantive actions, no decision that Pope Francis makes will be of greater consequence for reform of the Church’s bureaucracy than his choice of a secretary of state, the Vatican’s highest official, who oversees both the internal affairs of the Holy See and its relations with 180 other states.

Having filled that role for most of the previous pontificate, Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone has drawn most of the blame from outside critics for dysfunction within the Roman Curia. Whether or not the criticism is entirely fair, the cardinal is bound to step down soon, if only because he is already three years past the standard retirement age of 75.

Pope Francis, who has shown himself ready to defy precedent and conventional wisdom at least in matters of protocol, could, in principle, replace Bertone with just about anyone. Nevertheless, since the new Pope is from Latin America and has never studied or worked in Rome, he is likely to choose someone who shares the Italian nationality of the vast majority of the Vatican’s staff and who has some experience working inside its bureaucracy.

Yet choosing an insider presents obvious problems for reform, if nothing else because a Vatican resume would clash symbolically with any process of renewal. Hence the difficulty with two otherwise well-qualified and oft-mentioned possibilities: Cardinal Giuseppe Bertello, president of the commission governing Vatican City State; and Cardinal Fernando Filoni, prefect of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, who served under Bertone for four years as the “substitute” in charge of the Church’s internal affairs.

One name mentioned as a possible secretary of state even before Pope Benedict’s resignation was that of Cardinal Mauro Piacenza, prefect of the Congregation for Clergy, a man widely admired for his personal integrity and evident devotion. But his collapse in St. Peter’s Square during Palm Sunday Mass March 24, and his subsequent hospitalization for reported heart problems, hardly argue for his appointment to the stressful job of administrative reformer.

Hence the appeal of a choice that would have been almost unthinkable just weeks ago: someone with high-level experience in both the Vatican administration and its diplomatic corps, and who has shown himself ready to make enemies in the cause of reform.

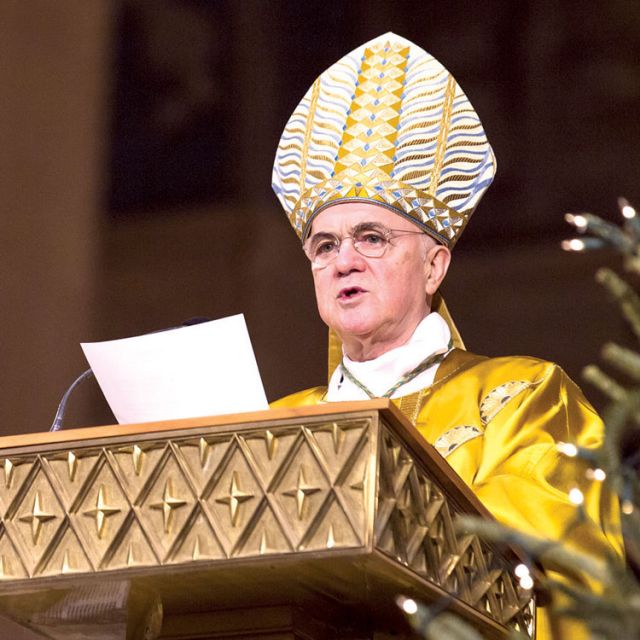

That would be Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano, formerly the second-highest official in Vatican City State, who wrote to Pope Benedict in early 2011, warning of “corruption and abuse of power long rooted in the various departments” of Vatican City and criticizing the inexperience of advisers who he said had led the Vatican to lose millions of dollars in bad investments. Pope Benedict named the archbishop nuncio to the United States in October 2011, and he remains in that position today.

When Vigano’s charges were published in early 2012, two cardinals took the unusual step of publicly rebuking him for his “erroneous evaluations” and “fears unsupported by proof” — reactions of a kind that ordinarily do not favour one’s rise in the hierarchy. But under a Pope who has shown himself more than willing to disturb the status quo, the archbishop’s notoriety may turn out to be his biggest recommendation.