The vandals stole money, tampered with security cameras and ransacked the principal’s office on Feb. 13.

The crime itself was relatively minor, but it rippled through other Christian schools. The attack was the sixth this year in an ongoing series targeting Christian communities and schools across India.

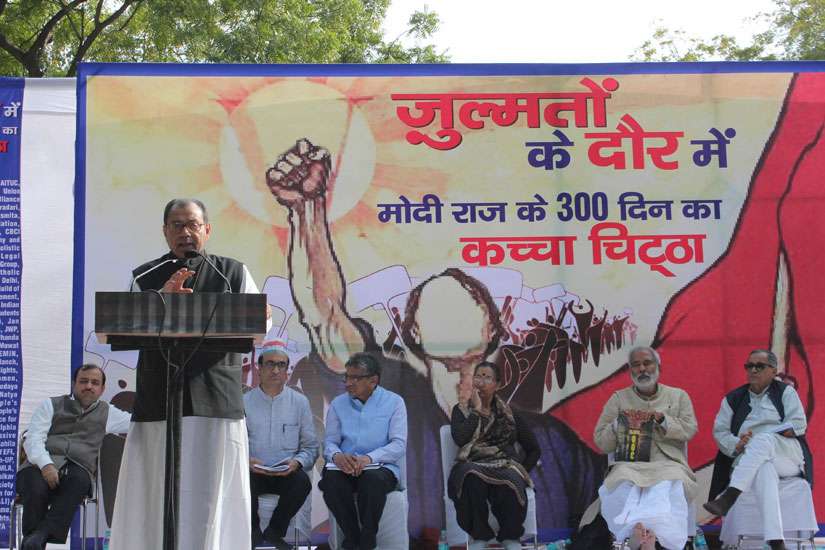

It was also the turning point for Prime Minister Narendra Modi to address the growing safety concerns of India’s minority Christian community. Modi immediately asked the Delhi police commissioner to investigate the attacks, and he addressed a Christian community, saying, “Government will not allow any religious group, belonging to the majority or the minority, to incite hatred against others overtly or covertly. Mine will be a government that gives equal respect to all religions.”

But even after Modi’s address, the attacks continued. In March, an elderly nun was raped in Calcutta and a Christian school in West Bengal received anonymous threats, according to a Times of India report. In April, St. Mary’s Church in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, was vandalized, setting off a wave of protests.

Earlier this month, the annual report of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom cited an “increase of harassment and violence” among India’s Christian community.

The attacks have come against a background of fear, triggered by Hindus in Modi’s party, that Christians are increasing their efforts to proselytize — especially in schools.

What is not widely understood outside of India is that these Christian schools are largely Hindu. Of Mount Carmel’s 2,500 students, for example, 75 per cent are Hindu, 17 per cent are Christian and fewer than two per cent are Muslim.

There are some Buddhist students as well.

The emphasis at Mount Carmel is not on religion but rather on values since most of the students — and teachers — are not Christians. This is common practice in India, and Christian schools have been known for their emphasis on quality education since the days of colonization.

Gauri Viswanathan, a professor in the humanities at Columbia University, has studied the ongoing discourse on conversion in India for decades. She said proselytizing in Christian schools was not as overt as perhaps imagined even back in the 19th century.

“Literacy through a Christian lens meant reading and learning English through Milton or other Christian scholars,” she said. “It was subliminal.”

Today, the curriculum focuses on academic prestige and achievement and not on religious instruction. Teachers such as Karthika Paul say they can instill a sense of values in their students without a religious framework. Paul, who teaches at Mount Carmel, said she focuses on producing students who can “overcome evil with good, forgive and be good citizens with good integrity.”

The only potential opening for evangelism is during the mandatory assembly each morning that includes a speaker and “Songs of Praise,” which include devotional hymns that translate well across a variety of religions.

Ankita Singh, an 11th-grade student, said she wasn’t sure she would embrace Christianity.

“My mom is a Christian and my dad is Hindu, so I am figuring out my faith,” she said. “It will come later, in its time.”

Many of the students say they enjoy the morning worship as a time to venerate their own deities.

While the current Bharatiya Janata Party government voices strong support for minority groups, it draws the line at conversion. Tarun Vijay, an elected member of the upper house of Parliament in India and a member of the BJP, said he was one of the first to stand up for equal rights for Christians, citing Jesus as one of the best examples of love. But proselytizing in Christian schools concerns Vijay.

Conversion, he said, is a remnant of colonial rule. “We firmly believe that converting Hindus to Islam or Christianity is a political movement that started with the British,” Vijay said.

He cited groups such as the Dalit Christians who were ostracized by Indian society and vulnerable to missionaries as easy converts. He said that these conversions are a threat to Hinduism.

John Thatamanil, a theology and world religions professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York, said that post-independence India has not had issues with proselytizing in Christian schools.

“You would have to look hard to find Christian schools as a means to proselytize,” he said.

At Mount Carmel, Principal Vijay Williams does not hesitate to explain his personal affinity to Christianity to visitors and students alike, even if he does not encourage sermonizing.

“Students are not forced to convert or even take a Bible class,” he said. “God converts them — we don’t convert them.”

Williams has reservations about Modi and the current government despite its response to the break-in. He cited secularism, defined in Articles 21 and 25 of the Indian Constitution, as a basis for Modi’s condemnation of violence against minorities.

“It is not a question of you standing with us,” Williams said. “It is a question of you standing with the Constitution.”

According to Columbia’s Viswanathan, waves of violence against Christians are not a new phenomenon.

“This is a deep-seated fear,” she said. “Even the East India Company would not allow missionaries into India until 1813.”

Viswanathan understands the recent violence as the religious right’s way of pushing its agenda forward. Social issues and attitudes are changing in India, as is the desire for a return to traditional Indian ideals. Economic development and progress are at odds with culture and tradition in India, she said, and this struggle is played out as a reaction to the potential change in the secularization of India.

At just 2.3 to 2.5 per cent of the Indian population, Christians do not pose a threat to the large Hindu majority in the country, and Thatamanil would like to see it stay that way.

“I don’t want a future where Christians and Hindus are pitted against each other,” he said.