Serra will be canonized on Sept. 23 in Washington, D.C., during the Pope’s visit to New York, Washington and Philadelphia. Francis has called on Catholics to emulate Serra and “respond with the same generosity and courage to the call of God” to become evangelizers. But the call to emulate Serra as he becomes a saint is being dampened by controversy.

Since Serra’s canonization was announced in January, many native American groups have launched protests. They claim that honouring Serra celebrates violence and even death that was inflicted on indigenous people in Spanish settlements and at the California missions founded by Serra during the era of Spanish colonization.

Boyd Cothran, a professor of U.S. Indigenous and Cultural History at Toronto’s York University, said he has been following the controversy since the canonization was announced. As a historian, he said it has been interesting to monitor the debate on both sides.

“It’s really complicated,” he said. “In a lot of ways, what does Serra represent? In their (native) minds, Serra represents the totality of the colonial experience, so when they’re criticizing Serra, they are criticizing coercive Christian colonization and massive deaths and loss of culture.”

Cothran said it is true that California missions established by Serra contributed to suffering and cultural upheaval for many indigenous people. However, Cothran believes it is wrong to hold Serra solely accountable for what occurred. Indeed, many historians absolve him of supporting Spanish policies to exploit and assimilate the native peoples.

Serra is often referred to as a founding father of the western United States. Starting in 1769, he opened the first nine mission settlements in what was then called New Spain. They stretched from San Diego to San Francisco and, in Serra’s view, were primarily to introduce Christianity to local populations.

Missionary work was his life’s calling. Born in Spain in 1713, Serra started out as a Franciscan friar on the Spanish island of Mallorca, where he taught theology at Lullian University in the village of Palma. Serra would read about missionaries in the New World but it wasn’t until he turned 36 that his desire for missionary work was answered.

In 1749, he embarked to Veracruz, Mexico. From there, he walked 400 km to Mexico City. On the way, his leg became swollen and infected from mosquito bites. He also developed asthma. These ailments would stay with him for the rest of his life.

He received intensive missionary training at Mexico City. For eight years, he worked to improve the living conditions of native peoples, teaching them skills such as farming, crafts and trades. Then for nine years he served as administrator and travelled on foot to preach about the missions. Serra would follow these same methods when, at the relatively old age of 55, he was sent to establish missions in California.

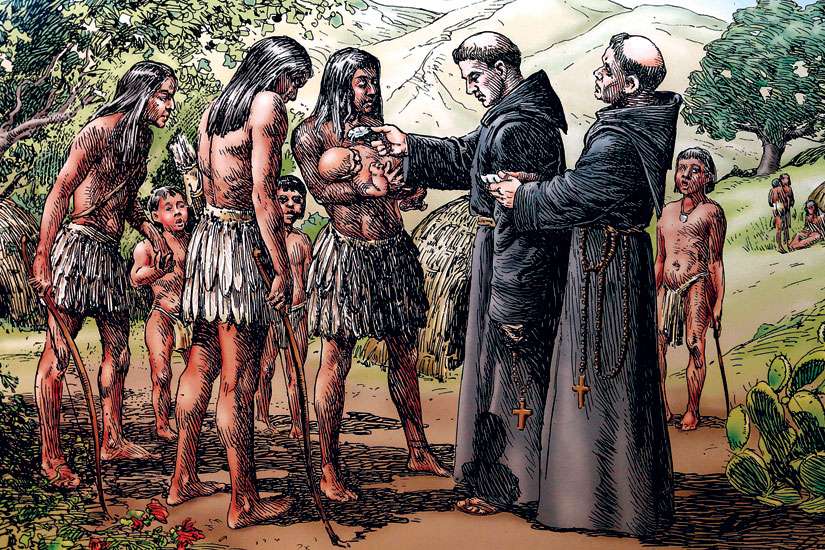

In California he worked alongside the Spanish military in missions that served both the Church and the Spanish crown. Wherever the Spanish military would establish a base, Serra and his fellow Franciscan missionaries would found a mission nearby.

In these missions, the native peoples were invited to live as catechumens, learning the faith and eventually being baptized. There is debate on whether or not the natives understood and embraced Christianity or whether they merely went to the mission to be fed, clothed and to learn land management and farming skills. What is clear is that mission life could be demanding.

The natives were treated like wayward children who needed to learn European ways. Discipline was rigidly enforced and routine punishment for relatively minor indiscretions included whipping.

Serra was a product of his times and supported corporal punishment. But he fought endlessly with Spanish soldiers and governors over excessively cruel mistreatment of natives. Eventually he created a set rules of engagement for the natives that became a foundation of California’s civil code.

“Serra did what he could to protect them and set up rules for how (Spanish soldiers) could interact with the Indians,” said Mario Biscardi, board treasurer for Serra International. “You can imagine the great pains and difficulties he had in keeping the peace.”

Biscardi said that Serra International has been working through its Serra clubs in the United States and Canada to inform people about the life of their lay organization’s patron. He said this event is an opportunity for the organization to teach others why Serra is a holy man deserving of celebration.

“(Serra’s) whole life is a second miracle,” said Biscardi. “He left a very cushiony job as professor of a seminary. He could’ve had it easy for the rest of his life, but he gave all of that up to be with the Spanish army and to convert the natives.”

During the last three years of his life, Serra travelled once more to visit the missions from San Diego to San Francisco to confirm all who had been baptized. He died at the age of 70 at Mission San Carlos Borromeo on Aug. 28, 1784. He baptized more than 5,000 natives and performed some 6,000 confirmations.

Biscardi said Serra’s zeal for saving souls inspires Serra International’s mission to encourage and support vocations among the global Catholic community. Through Serra International Foundation, they support seminaries, houses of religious orders and other institutions that promote priesthood and consecrated religious life.

Serra International, which has promoted and supported global vocations since 1935, adopted Serra as its patron saint in 1937 and has been praying for Serra’s canonization since his beatification by St. John Paul II in 1988.

“We have a prayer that we say at the opening of all our meetings. This is something that Serrans across the world have been praying for for many years,” said Lee Hishon, board secretary of Serra Canada.

To have those prayers answered only to see opposition and controversy to Serra’s canonization is unsettling, Hishon admits.

“One of the things that can be a bit disturbing is that he has gotten a lot of negative publicity. Some of it seems to be quite unfair,” he said.

“Native Americans might show up to protest this and I’m hoping not. That’s one of the things that we’re praying for.”