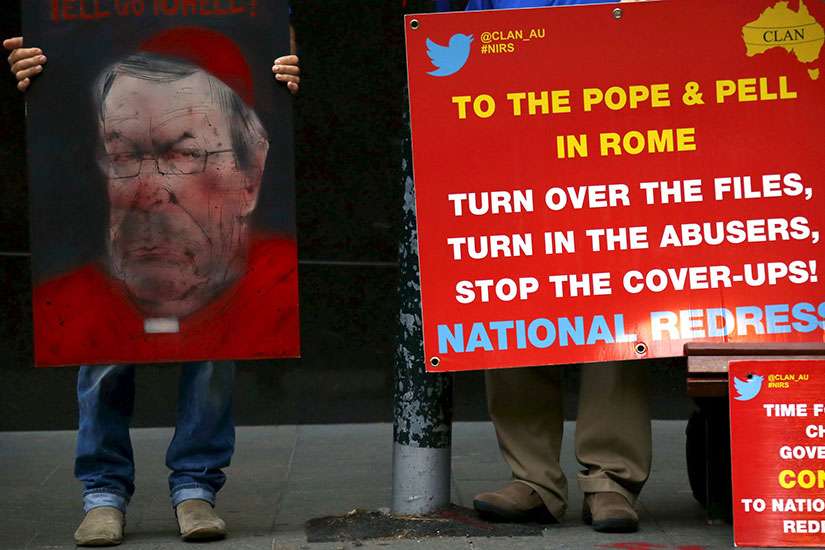

The focus of Cardinal George Pell's testimony to Australia's Royal Commission Into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse March 2 was on Pell's time as auxiliary bishop of Melbourne between 1987 and 1996 and the case of Fr. Peter Searson, the parish priest of Holy Family School in Doveton.

In its three years of investigations, the Royal Commission has heard stories about Searson ranging from sexual harassment to rape of young boys. Australian police have voiced frustration that parents were unwilling to press charges.

Pell, prefect of the Vatican's Secretariat for the Economy, testified overnight via video link from a Rome hotel for about five hours. He described Searson as a "disconcerting man" who, at his worst moments, could be one of the most unpleasant priests he had ever met.

Even prior to Pell's arrival in Melbourne, there had been a litany of complaints made to then-Archbishop Frank Little about Searson's conduct. These included pointing a handgun at students and taking a tape recorder into the confessional, as well as requiring female students to either sit on his lap or kneel between his knees during confession.

There was also at least one complaint of a sexual advance toward a female student, and the school principal had resigned in order to raise attention to the conduct.

In earlier sessions, the commission heard that after Pell's appointment as auxiliary bishop with responsibility for the region, including Doveton, a delegation of concerned teachers from the school went to see him. They gave him a "list of grievances," which included Searson's unnecessary presence in the school bathrooms; harassment of staff, parents and students; incidents of animal cruelty; and showing the children a dead body in a coffin, all matters which Pell reported back to the archbishop.

Pell told the commission that he did not know of the earlier complaints about Searson or the suggestion of sexual misconduct and was not told about them by Catholic Education Office staff in a briefing prior to meeting with the teachers' delegation. He agreed that this amounted to a deception.

As they had done the previous day, Gail Furness, senior counsel assisting the commission, and Justice Peter McClellan, commission chair, challenged the cardinal on this evidence, arguing that staff would have no reason to keep the information from him if it had already been presented to the archbishop.

Pell responded by saying that he differed greatly with Little on his approach to matters, so education staff could have been protecting Little from interference from his auxiliary bishop. Pell said he had also been publicly critical of the archdiocesan approach to religious education, which he surmised might have increased the education staff's reluctance to deal with him.

Furness called Pell's testimony "completely implausible" and challenged testimony he had given in previous days that the bishop of Ballarat had kept information about offending priest Gerald Ridsdale from him.

"It's an extraordinary position, cardinal," she said.

"Counsel, it was an extraordinary world," the cardinal replied, "a world of crimes and cover-ups, and people did not want the status quo to be disturbed."

Asked if he had put himself in that world to disturb the status quo, Pell replied that his record as archbishop of Melbourne showed that he not only disturbed the status quo but turned it around.

The redress procedure he introduced, he said, was light years ahead of others. Its 1996 introduction predated by some years even reporting of the child sexual abuse scandal by outlets such as The Boston Globe, whose 2002 expose of the abuse in that diocese was the subject of the Oscar-winning film Spotlight.

Toward the end of the questioning, McClellan noted that the commission could recommend changes to Church structure in its final report. He said the failures in management of abuse were indicative of the need to implement a significant "middle management" structure, such as those seen in corporations with hundreds of branch offices.

Pell said a model that attempted to place an intermediary between a priest and his bishop was not a Catholic one, and that other changes could be made without having to abandon the traditional structures of the Church.

McClellan told the cardinal that the issue would be revisited at a subsequent hearing later in the year.

The cardinal's March 3 testimony, expected to be the final day, was to begin at 9 p.m. in Rome March 2 and last six hours.