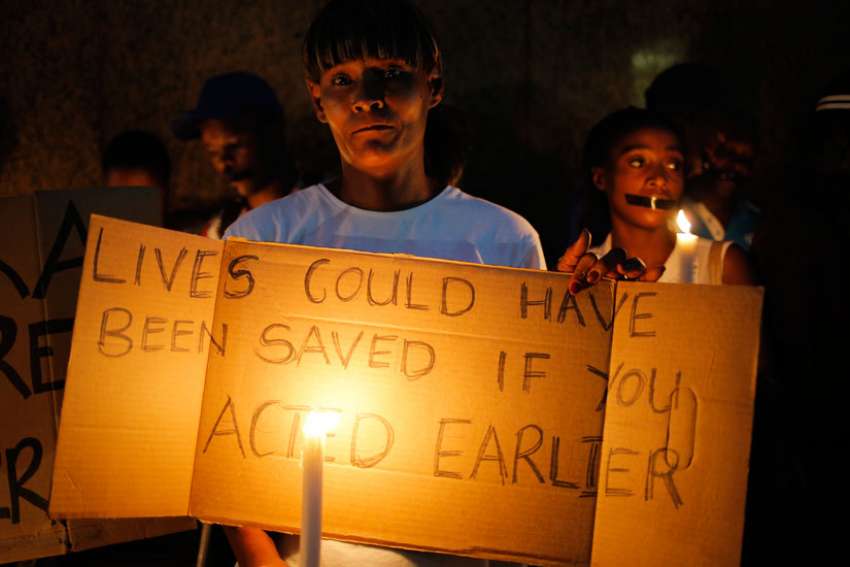

Deaths caused by dehydration, septic bed sores and uncontrolled seizures followed the transfer of more than 1,300 patients from a hospital to unlicensed nongovernmental organizations, said a Feb. 1 report by South Africa's health ombudsman, Malegapuru Makgoba.

The report's findings show "a shocking failure to provide fundamental psychiatric health care" as required by South African law, the Johannesburg-based Jesuit Institute said in a Feb. 2 statement.

"It is particularly disturbing to see how vulnerable people ... have been subjected to what is, in effect, a cynical, and almost certainly profit-motivated, curtailment of basic care," it said.

The ombudsman found that the centres that housed patients failed to provide seriously ill people with enough food and water, leaving them severely malnourished and, in some cases, dying from dehydration.

Remedial action must include holding to account those responsible "for this gross violation of human rights" and "suitable reparations according to the gravity of the damage," the Jesuits said.

The provincial government should ensure that families who lost loved ones are "expeditiously compensated," the Southern African Catholic Bishops' Conference justice and peace commission said in a Feb. 3 statement.

"Speedy resolution of claims is an important step toward the healing of the affected families," the Pretoria-based commission said, noting that efforts should be made to avoid lengthy court cases "that would deepen the wounds of affected families."

The transfer of the patients in 2016 was rapid and chaotic, and the 27 "mysteriously and poorly selected" organizations transported people from Life Esidimeni hospital in open pickup trucks after choosing them as if they were at "an auction cattle market," the ombudsman's report said.

"By undercutting basic standards of care, what we have seen is contempt for the right of vulnerable people to the basics of a decent life," the Jesuit Institute said, noting that "this has resulted in disastrous and, in many cases, lethal consequences."

Gauteng's provincial health department terminated its long-standing contract with the hospital in an apparent cost-cutting measure.

"Those in public service, whether they directly participated or were complicit in what has happened, should not be allowed near vulnerable people, especially mental health patients, in future," the Jesuits said.

"We are deeply disturbed that those responsible for making these decisions ignored the advice of many competent consultants and professionals," they said, noting that "this arrogance has led to painfully tragic circumstances."

Also, "the state should institute a comprehensive review of its practices" to ensure that this "never happens again," the institute's statement said.

The justice and peace commission urged the province's health department to stop the "de-institutionalization of mental health care" until strong measures are in place to guarantee the protection of human rights while community-based care is implemented.

"Protecting the lives of the psychiatric patients, as one of the most vulnerable groups in our society, is more important than achieving budget efficiency," the commission said.

Provincial health minister Qedani Mahlangu resigned over the findings, which implicated her in moving patients to an "unstructured, unpredictable, substandard caring environment."

The ombudsman gave the province's health department 45 days to ensure that all remaining patients are "urgently removed and placed in appropriate health establishments."