Now the Catholic bishops of South Korea are considering whether he should beatified among a group of Korean martyrs.

“Bishop Byrne is one of the unsung heroes of Maryknoll,” Father Raymond Finch, Superior General of the Maryknoll Society, told CNA. “We remember him as an example of a missioner who stayed at his post.”

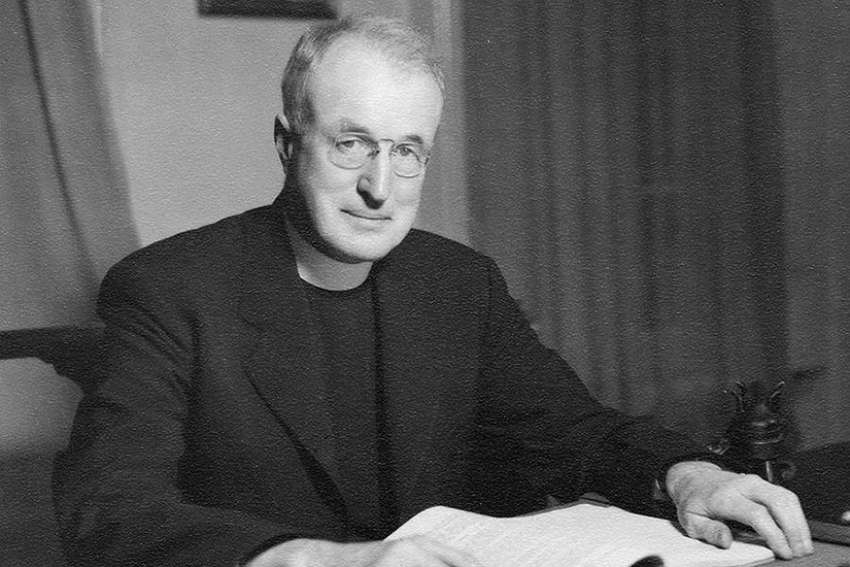

As a newly ordained priest in 1915, Bishop Byrne joined the Maryknoll Society, just four years after its founding. He led the society's mission to Korea in the early 1920s, and he served as prefect apostolic of Pyongyang from 1927 to 1929.

In the 1930s he was transferred to Japan, and during World War II he was held under house arrest.

After the war's conclusion, he was named the first apostolic delegate to Korea, in April 1949. He was promptly ordained a bishop, at the age of 60.

His ordination came at a portentous moment early in the Cold War. Korea was splitting between the North Korean communists, backed by China and the Soviet Union, and the U.S.-backed South Korea.

With the rise of communism in northern Korea, many of the Catholics in the north, including Maryknoll clergy, had to escape to the south in order to continue to practice their Catholic faith.

But not Bishop Byrne.

“It was then, remaining at his post, that he was taken with many other religious priests and members of the Church, taken prisoner on a forced march,” Fr. Finch said. “And he died on that march.”

In July 1950, after the capture of Seoul by North Korean forces, Bishop Byrne was arrested by communists and put on trial. According to Glenn D. Kittler’s history “The Maryknoll Fathers,” he was threatened with death if he did not denounce the U.S., the United Nations, and the Vatican. He refused.

He and other priests were put on several forced marches with Korean men and women and captured American soldiers.

Bishop Byrne was known for trying to help others on the marches through the cold, wet Korean weather, Fr. Finch said.

Aiding others was risky. Some of the prisoners were shot for dropping out of line, while others were executed for aiding those who had become immobilized. Nonetheless, the bishop would help others. At one point he gave his entire blanket to a Methodist missionary who was suffering worse than he.

During a four-month-long forced march, suffering from bad weather and a lack of food and shelter, he began to succumb to pneumonia at Chunggan-up, not far from the Yalu River on the border with China.

He knew he was dying.

“After the privilege of my priesthood, I regard this privilege of having suffered for Christ with all of you as the greatest of my life,” he told his companions.

He received absolution from his secretary, Father William Booth, the bishop’s biography at the Maryknoll Mission Archives website says.

He died Nov. 25, 1950. News of his death took two years to reach the world, when U.N. prison camp inspectors found survivors of the march.

Bishop Byrne was buried by Msgr. Thomas Quinlan, an Irish-born Columban Father who placed his own cassock on the bishop. The monsignor was later named Bishop of Chunchon, South Korea.

Now, a special commission of South Korean bishops has begun a process that could make Bishop Byrne a candidate for beatification. The bishops have grouped him with Bishop Francis Borgia Hong Yong-ho of Pyongyang and 80 companions, who were killed in persecutions from 1901 to the mid-20th century.

Fr. Finch said the launch of the beatification process for Bishop Byrne was “a tremendous honour” and showed he was an example for the Maryknoll Society to follow.

“He answered the call to mission, from the very beginning, and stayed with it, and gave his life to that,” he said. “That’s what we want to do, one way or another, whether it’s through a lifetime, or in a moment in which supreme sacrifices are asked for.”

“We’re inspired,” the Maryknoll superior general said. “We’re inspired by him, and we’re inspired by a number of other Maryknollers who have given their lives over the years in Asia, in Latin America and in Africa.”

Other victims of the Korean conflict include Maryknoll Sisters like Sister Agneta Chang, who was kidnapped by the communist military in late 1950 and is believed to have been martyred.

“I believe they never found her body,” Fr. Finch said.

While the context of the conflict was very difficult, it led to “tremendous Church growth” in South Korea after the war from people who were dedicated to the Church.

“Korea is one of the tremendous success stories of Asia: a Church that started out with 20-25,000 of people of the faith at the start of the last century and ended up with 10 percent of the population today,” Fr. Finch told CNA.