Those Huron-Wendat were the very people, the very culture, which attracted French Jesuit missionaries to a protected cove off Georgian Bay where in 1639 they established the fortified village of Sainte Marie and dreamed of a Christian, Huron-Wendat kingdom — a new incarnation of Christ in a culture the Jesuits and these new Christians would shape together.

This may be distant, ancient history for most Catholics in this region today, but it is our history. The Archdiocese of Toronto did not simply drop from the sky as arguably the Catholic world’s most culturally diverse archdiocese of over two million Catholics who celebrate the Eucharist every Sunday in about 35 languages. We didn’t get to baptizing almost 15,000 new Christians every year and caring for souls in 225 parishes plus about two dozen missions overnight. Half-a-dozen Catholic health care institutions didn’t materialize out of thin air. We have not arrived at almost 500 elementary schools, over 100 high schools and three degree-granting institutes of higher learning without struggle, sacrifice and the grace of God.

The archdiocese itself was officially created in 1841, but all that struggle, sacrifice and grace began more than a hundred years earlier with St. Jean de Brébeuf and his Jesuit brothers, who in 1639 built their Christian village near modern-day Midland and wrote home to France about the endeavour. Their letters were collected and published as the Jesuit Relations. In monthly installments, the Relations became some of the most popular literature in Paris at the time of King Louis XIV, just as that new technology, the printing press, was taking off. Brébeuf’s dreams and enterprise infected a generation of young Frenchmen who swelled the ranks of the Jesuits over the century.

But the missionaries had to abandon and burn down their own village in 1649 so it would not fall into the hands of marauding Iroquois, who were allied to and armed by the Dutch. Brébeuf and his brothers were all eventually martyred as sort of collateral damage in the bloody Beaver Wars (off and on between 1628 and 1698).

Brebeuf’s dream died and Europeans became colonizers rather than sharers of the land. There were no new Christian kingdoms, but lots of battles among the old ones. Toronto grew up in the aftermath of the 1759 British conquest of New France and as a defence against the Americans after the 1776 revolution.

St. Jean de Brébeuf and fellow Jesuits are remembered at the Martyrs’ Shrine in Midland, Ont. (Photo by Michael Swan)

St. Jean de Brébeuf and fellow Jesuits are remembered at the Martyrs’ Shrine in Midland, Ont. (Photo by Michael Swan)

This history of conquest, conflict and colonization endured and shaped the politics and priorities of Toronto. Between 1951 and 1991 Torontonians bulldozed and built over about 8,000 mostly aboriginal archaeological sites, according to Archaeological Services Inc. Our carelessness helped us build a modern metropolis and erase our memory of the Huron-Wendat.

However, Canadian Catholics never quite forgot New France. Through the 19th century there was a movement to canonize the 17th-century Jesuit martyrs. Finally, in 1930 St. Jean de Brébeuf and seven of his brothers were declared saints as the “Canadian Martyrs.” Since the Martyrs’ Shrine was established 91 years ago in the northern reaches of the Archdiocese of Toronto, it’s been hard for a Catholic in the archdiocese to ignore that we have a history which predates British imperialism.

There had been Catholics in Upper Canada even when its first lieutenant governor, Lord John Graves Simcoe, was setting aside large clergy land reserves for the Anglican Church. There were 170 Catholics in York in 1802 and by 1822 the little community had scraped together the money to build the first gothic, red-brick version of St. Paul’s Church (now a basilica) the first mother church of Catholic Toronto.

Canada had by this time invented a new form of poverty. Traditionally, wealth had rested on a foundation of land. You couldn’t have land and be poor, except in Canada. British trade policies had driven the price of grain below the cost of growing crops. Toronto farmers sensed others were getting rich while they starved. They also saw that representative government in the United States was building a more equal society. All while Toronto was being run by a cabal of self-important, well-connected English, Anglican and Methodist families known as the Family Compact.

When the Diocese of Toronto was created in 1841 — carved off from the Diocese of Kingston — and Canadian-born Bishop Michael Power installed in St. Paul’s in 1842, the issues of the past were far from settled. Those issues were almost as vast as his new diocese, which stretched from present-day Oshawa to Windsor, across the Niagara Peninsula and north to the shores of Lake Huron and even Lake Superior.

Bishop Power quickly saw that his Church needed to be re-oriented to serve the faithful. In a Canadian Church dominated by francophone Quebec bishops, the anglophone Upper Canada clergy whom Bishop Power came to rule had been operating pretty much without supervision for years. Some of their pastoral sense had possibly abandoned them, as illustrated by Fr. John O’Grady’s refusal to baptize the son Francis Collins, publisher of the Canadian Freeman newspaper (a predecessor of The Catholic Register) because Collins’ brother had sued Fr. O’Grady in pursuit of an unpaid debt.

The first Roman Catholic provincial council with bishops from around Ontario gathered in Toronto in 1875. Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

The first Roman Catholic provincial council with bishops from around Ontario gathered in Toronto in 1875. Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

“The servant of the Lord must not wrangle, but be mild toward all men, apt to teach, with modesty admonishing them that resist the truth,” Bishop Power wrote to his priests in May of 1842. “... Feed the flock which is among you, taking care of it not by constraint, but willingly according to God; not for filthy lucre’s sake but voluntarily.”

Bishop Power demanded that his priests not charge for the administration of sacraments, that they stop presiding at weddings in private homes and that records be kept. However, the young bishop needed manpower to serve his vast diocese of 25,000 Catholics, so he appealed to the Jesuits for a new generation of missionaries — and got them.

By 1847 Bishop Power had 25 priests, including 10 francophones and seven Jesuits. Still shorthanded, he headed for Europe and Ireland to recruit more. While in Ireland he saw the suffering inflicted by the politically induced potato famine. He returned to Toronto in time for a summer influx of Irish refugees. A town of 20,000 saw 38,560 Irish refugees pass through that summer, most of them on their way to Boston and New York. But many of them never made it past Toronto’s fever sheds, where they died of typhus.

Bishop Power died with them, having spent his summer visiting the sheds with his daily supply of holy oil and consecrated hosts. He was 42 years old. He was buried near the foundations of St. Michael’s Cathedral while it was still under construction.

In 1845, Bishop Power had brought Protestants and Catholics briefly together by promising to barbecue an ox for everybody willing to voluntarily clear the site and dig the foundations of St. Michael’s Cathedral. But that unity was not what Toronto became famous for in later years, when it was known as the “Belfast of Canada.”

There were about 14,000 Orangemen in Canada in 1834, with a particularly vigorous concentration in Toronto. By the 1860s over a quarter of Toronto’s 50,000 people were Irish Catholics but a large number of them were stuck in slums in Corktown and Cabbagetown and used as a pool of despised, disposable, unskilled labour. In a 25-year-span between 1867 and 1892, the Orange Order waged pitched street battles with Toronto Catholics at least 22 times.

On Sept. 25, 1875 Catholics were celebrating the jubilee year decreed by Pope Pius IX with a pilgrimage to St. Michael’s Cathedral. The procession was met by armed Orangemen. Between 6,000 and 8,000 Toronto citizens were caught up in stone throwing, fist fights and a few shots fired along the route. The Toronto Globe criticized Catholic leaders’ for lack of tact in advertising the pilgrimage.

In the middle of the turmoil, poverty and difficulty of 19th-century Catholic life, the Sisters of St. Joseph arrived. Mother Delphine Fontbonne and three of her sisters came from Philadelphia in 1851 at the request of Bishop Armand-François-Marie de Charbonnel. In four years, Mother Fontbonne established an orphanage, several schools, a motherhouse and novitiate, an academy and boarding school, and a house of refuge.

In 1855 Toronto was hit with another typhus epidemic. Mother Fontbonne attended to the sick and contracted the disease herself. She died on Feb. 7, 1856, leaving behind a community of almost 50 religious sisters.

The original House of Providence in 1914. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

The original House of Providence in 1914. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

The Sisters of St. Joseph of Toronto went on to establish the House of Providence in 1857, St. Michael’s Hospital in 1892, teach in almost every Catholic elementary school by 1900, then found St. Joseph’s Hospital in 1921, St. Joseph’s High School for girls in 1949, St. Joseph’s Morrow Park High School in 1960, St. Michael’s Homes for recovering addicts in 1974, the Daily Bread Food Bank in 1982, the Furniture Bank in 1998, Faith Connections for young adult ministry in 2005. Exhausting as it might be, this is not an exhaustive list. They did even more.

The Basilian Fathers arrived in 1852 and established St. Michael’s College to provide the secondary and post-secondary education Catholic boys were mostly excluded from in Orange Toronto. By 1910 St. Michael’s was federated with the University of Toronto. The Basilians also persuaded internationally renowned, Sorbonne-based father of modern mediaeval studies Etienne Gilson to set up the Institute of Mediaeval Studies. It became the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies in 1939.The Basilians still run St. Michael’s College School and St. Basil’s parish on the U of T campus.

In 1893 Toronto Catholics came up with a new tactic for challenging the Protestant consensus that surrounded them. A group of Irish Catholic businessmen launched The Catholic Register to be the voice for the region’s largest, most visible and most disliked minority. They took over from the Irish Canadian which had taken over from Collins’ Canadian Freeman. Patrick Boyle’s Irish Canadian had railed against the anti-Catholic atmosphere of a city “in the hands of an Orange mob, aided in their work of blood and ruin by an Orange Mayor.” This wasn’t just rhetoric. In 1856 there was an attempt to blow up the House of Providence. In 1858 a riot instigated by Orangemen ended in the murder of Matthew Sheedy, a young Irish Catholic.

“Doubtless every intelligent man is aware that as far as an Irish priest is concerned he is loyal to no being but the Pope, and to no place but Rome. Loyalty! The thing is a joke. An Irish priest is not and cannot be loyal to our Queen, our Empire, or our people. He has no part or lot with us. He has no interest in us. He is an alien though born within the bounds, and his oath of fealty is to the kiss of Judas. He lives to serve Rome and to crush Protestantism,” wrote the Globe on Feb. 18, 1856.

Beer and energetic Irish prelates were the foundations of Toronto’s Catholic life in the 20th century. Archbishop Fergus McEvay guided the Archdiocese from 1908 until his death in 1911, but in three years he founded the Catholic Church Extension Society, laid the cornerstone for St. Augustine’s Seminary and increased the number of parishes to 92 to serve 70,000 Catholics. McEvay also encouraged Fr. John Mary Fraser who would found the China Mission Society, later renamed the Scarboro Missions.

But McEvay’s smartest move might have been to tell the rector of St. Michael’s Cathedral, Fr. Martin Whelan, to go talk to a widower frequently found in the church in 1909. The widower happened to be one of the richest men in Canada, Eugene O’Keefe — the city’s pre-eminent brewer, banker and business tycoon.

Cardinal James McGuigan at the blessing of the military veterans cemetery at St. Augustine’s Seminary in October 1941. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

Cardinal James McGuigan at the blessing of the military veterans cemetery at St. Augustine’s Seminary in October 1941. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

O’Keefe was already a major donor to the archdiocese. The beer baron had one day noticed poor Polish Catholics at the cathedral, following the Latin but unable to understand English, who had walked miles to Sunday Mass. Their faith inspired O’Keefe to buy an old Presbyterian church for $30,000 and donate it to the Poles, who transformed it into St. Stanislaus.

In 1969 Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, the future St. John Paul II, came to St. Stanislaus for a visit and to thank Toronto’s Polish Catholics for their support both during World War II and after, as the Church endured communist rule.

In 1909 there was nowhere outside of Francophone Quebec to study for the priesthood. If the English Canadian Church was to grow it needed a seminary. O’Keefe came through with $450,000 — more than $10 million in 2017 dollars. By 1913 St. Augustine’s Seminary was training priests for Toronto and the vast mission territories to the West.

In the First World War, Canadian Catholics died or came home shell shocked and wounded. That generation knew the war had not been for a noble purpose. Then 1929 hit, wages fell, farms failed and industry ground to a halt. The prodigiously educated and energetic Archbishop Neil McNeil was ready for the Great Depression with Harry Somerville in place as editor of The Catholic Register and instructor in the social doctrine of the Church at St. Augustine’s Seminary.

The old truths and the old hierarchies could not survive the twin blows of the useless waste of the Great War and then the economic failure of the Great Depression. The Church feared it might lose the souls of working men to an atheistic promise of justice offered by various brands of socialism and communism. With the founding of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation in 1932, Canadian socialism went mainstream. Somerville had to convince the bishops not to ban Catholics from joining the forerunner of today’s NDP.

By the time Archbishop McNeil died in 1934 there were 165,000 Catholics being served in 126 parishes and missions in the Archdiocese of Toronto. The next year, the China Mission Society had 50 young men in its seminary at the Scarborough bluffs studying to become missionaries. In 1937 Msgr. John Edward Ronan, a graduate of the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in Rome, had established St. Michael’s Choir School.

Through the middle of the 20th century Toronto Catholics had two fights on their hands. They had to fight for their fair share of education funding in Ontario and they had to fight to fund Catholic social infrastructure.

In 1927 Archbishop McNeil founded the Federation of Catholic Charities in response to a decision by the city’s Federation for Community Service not to fund any of the Catholic organizations. Fifty years later Archbishop Philip Pocock had to repeat the operation, withdrawing the Council of Catholic Charities from the United Way in 1976 rather than see Catholic charitable contributions go to support Planned Parenthood — thus the birth of ShareLife.

Pope John Paul II at the 2002 World Youth Day in Toronto with, from left, Cardinal Jean-Claude Turcotte, Cardinal Aloysius Ambrozic and Archbishop Marc Ouellet. (Photo by Catholic News Service)

Pope John Paul II at the 2002 World Youth Day in Toronto with, from left, Cardinal Jean-Claude Turcotte, Cardinal Aloysius Ambrozic and Archbishop Marc Ouellet. (Photo by Catholic News Service)

Archbishop McNeil waged a constant battle for fair taxation, meaning a fair share of taxes should fund Catholic schools. In 1929 he appealed to the Toronto District Trades and Labour Council arguing that the wealth Catholic workers create in Toronto should not be siphoned off to pay for a public school system at the expense of a constitutionally guaranteed Catholic education.

“I want to ask you — do you consider that the men who are working for these companies have any right or any claim upon the school taxes paid by those industries?” Archbishop McNeil asked the powerful labour movement leadership.

In 1946 Archbishop McNeil’s successor, Cardinal James McGuigan was still at it, submitting a brief to a royal commission shaping the post-war education system in Ontario. He asked why, if the Catholic schools educate one-fifth of Ontario’s elementary pupils, the schools only receive one-eighth of the education funding.

The argument dragged on until Cardinal Gerald Emmett Carter, with the help of his predecessor Archbishop Philip Pocock, was able to make the same argument over and over to Premier Bill Davis. Davis was a sometimes dinner guest at Cardinal Carter’s home and in Brampton he was Archbishop Pocock’s neighbour, as the former archbishop spent his declining years fighting cancer, helping out at St. Mary’s Church and quietly lobbying the premier.

With court rulings in favour of the Catholics looming, Brampton Bill magnanimously gave in. In 1985 Catholic families could finally send their kids to a Catholic high school without paying tuition. The deal was under threat, especially from the public school teachers’ unions, until a 1987 Supreme Court of Canada reference settled the question.

There followed a boom in Catholic school building and by 1999 there were 41 Catholic high schools in the Toronto Catholic District School Board alone.

During the Second World War working class Catholic boys died on the front lines and the archdiocese lived in constant mourning and grief. But there was outrage too. This was a fight against evil. On April 25, 1942 the banner headline across six columns of The Catholic Register’s front page trumpeted “Vigorous Answer To Nazi Blasphemies.” The war was by then a battle of blood on its way to claiming more than 45,000 young Canadian lives. But for Catholics it was also a spiritual fight. Catholic Register readers were signing up to become members of “The Crusade of the Cross of the Sword of the Spirit Movement” led by Canada’s bishop in ordinary to overseas forces, Bishop Charles Nelligan.

After the war, a flood of European, Catholic immigrants came to build lives in the archdiocese. Out of that experience came Toronto’s Cardinal Aloysius Ambrozic. As a young refugee Ambrozic had struggled through high school while his family moved through various displaced persons camps in Austria. The brilliant young Slovene was resettled with his family in Toronto in 1948 and enrolled in St. Augustine’s Seminary. He was ordained in the largest ordination class in the seminary’s history, 53 new priests in 1955.

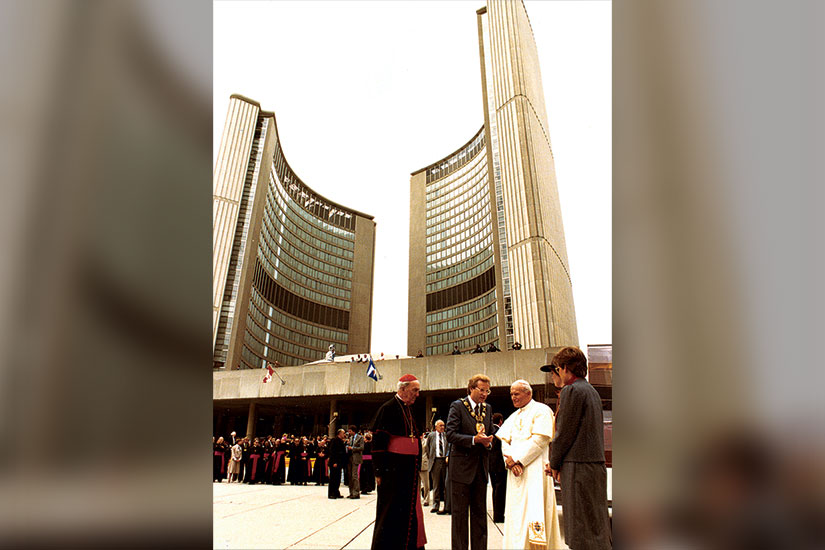

Pope John Paul II at Toronto City Hall with Cardinal Gerald Emmett Carter and Mayor Art Eggleton in 1984. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

Pope John Paul II at Toronto City Hall with Cardinal Gerald Emmett Carter and Mayor Art Eggleton in 1984. (Photo courtesy Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto)

The new priest was surrounded by priests who had served in the war, who had witnessed industrial-scale killing, who knew Auschwitz was possible and sought to serve ordinary people. By 1990 he was a bishop and was surrounded by a generation of Church leaders keenly aware of how ordinary people suffer in a world created by remote forces that declare wars, proclaim ideologies, define economies and dictate the terms of our culture. Toronto Catholics responded to those opaque economic forces in 1987 by following Sr. Susan Moran in founding the Out of the Cold program. Church basements and parish halls were made available one night a week to shelter the homeless.

Cardinal Ambrozic seized upon Pope John Paul II’s idea of a culture of life opposed by a powerful culture of death. For the rigorous and elegantly educated Scripture scholar, that culture represented the ideals of working class Italian and Portuguese immigrants and a new wave of Asian Catholics — led by Filipinos and Tamils — who were steadily arriving.

By the turn of the century, with 1.5 million Catholics and nearly half of the city’s population born outside of Canada, this big, vibrant, immigrant Church was ready for the world stage. The Archdiocese of Toronto was chosen as the site for the most ambitious World Youth Day pilgrimage and festival in the history of the event.

Half a million youth from around the world came to be told “You are the salt of the earth… You are the light of the world.” St. John Paul II preached through the rain to nearly one million at Downsview Park until the sun shone through.

“Even a tiny flame lifts the heavy lid of night,” Pope John Paul II told his last World Youth Day crowd. “How much more light will you make, all together, if you bond as one in the communion of the Church?”

In 2012 Archbishop Thomas Collins inherited the vast, ambitious project of Bishop Michael Power — now with nearly 400 diocesan priests, more than 400 religious priests, more than 500 religious sisters and well over 100 deacons serving some 225 parishes. Moved by the vision and ambition of Toronto’s founding, martyr bishop, the archbishop decided to rebuild his church.

He arrived to discover that St. Michael’s Cathedral was falling down. And perhaps that danger symbolized a threat confronting an archdiocese which had grown into a spirit of possibility but without a plan to realize all its potential.

In 2014 Cardinal Collins launched the Archdiocese of Toronto’s first ever pastoral plan. By 2016 he had completed, more or less, one of that plan’s first priorities. St. Michael’s Cathedral was restored. In homage to Michael Power’s vision, St. Michael’s is in truth, a brand new, $128 million cathedral which proudly wears its history in Toronto bricks shaped by clay from the Don Valley.

It didn’t come from nothing.

St. Michael’s Cathedral was rededicated as a basilica in September 2016. (Photo by Michael Swan)

St. Michael’s Cathedral was rededicated as a basilica in September 2016. (Photo by Michael Swan)