A tall, white steeple atop the red-brick Holy Trinity Catholic Church — which opened in 1903, four years before Oklahoma became the 46th state — points toward the slightly cloud-covered sky.

Yellowish-green grass and brown fields awaiting the planting of the next wheat crop in a few months adorn the prairie as men in western shirts, women carrying babies and children in shorts and dresses fill the pews.

They’ve come — a standing-room-only crowd of nearly 400 — to pay tribute to a hometown hero who could become a saint.

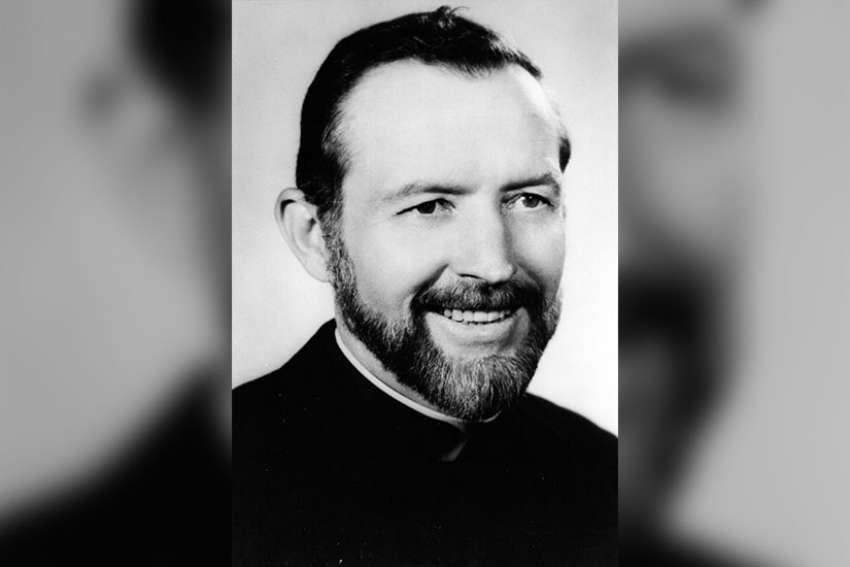

“It’s hard to really put into words,” said Marita Rother, a nun and younger sister of the priest who was shot to death on July 28, 1981, while serving as a Catholic missionary during Guatemala’s bloody civil war.

“I think the whole thing is beyond what any of us would expect to be happening,” she added.

”Year after year, the slain priest’s childhood church celebrates a special anniversary Mass remembering the sacrifice Rother made to serve Mayan descendants in a poor, mountain village 50 miles west of Guatemala City.

But this year, the memorial service took on added meaning and drew a larger crowd: Last December, Pope Francis recognized the Oklahoma native as the Catholic Church’s first U.S. priest and martyr to be approved for beatification. The Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of the Saints declared Rother had fulfilled the requirement of having died due to “hatred of the faith.”

Now, excitement builds for a Sept. 23 beatification ceremony expected to draw up to 12,000 to the Cox Convention Center in Oklahoma City.

“We have people coming in from all across the country and all across the world,” said Archbishop Paul S. Coakley, who gave the homily at the memorial Mass.

Beatification is the last major step before sainthood — a fact that both thrills and amazes Rother’s loved ones in this farm town of 1,200, about 40 miles northwest of the state capital.

“To be a guy who came out of a little old farm out here, it’s just hard to believe,” said the priest’s brother, Tom Rother, his voice breaking with emotion.

Nobody expected the farm boy born during an Oklahoma dust storm in 1935 to become a priest — much less a saint.

As a high school student at Holy Trinity Catholic School, Rother took a vocational agriculture course. His brother studied Latin. Family members still chuckle that Stanley became a clergyman, while Tom stayed on the farm.

Later, Rother struggled with Latin and flunked out of his first seminary. But he stuck with his studies and eventually graduated from a different seminary. He was ordained in 1963 and served several Oklahoma parishes before volunteering for mission service in Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala, in 1968.

In his 13 years in Guatemala, the priest who had trouble with Latin learned Spanish and his parishioners’ Tz’utujil language, even working to translate the New Testament’s Gospels into the native dialect.

Amid political and military unrest in the late 1970s, parishioners began disappearing, their bodies found dumped on roadsides. By 1981, Rother knew that he was on a “hit list,” according to the Oklahoma City archdiocese.

Several other Catholic priests — at least 13 — were killed during the war, branded as communists in collusion with left-wing revolutionary guerrillas.

But after a final trip home to visit his family early that year, the 46-year-old priest returned to Guatemala in time for Holy Week.

“He knew what was going to come,” Tom Rother said. “He said, ‘The shepherd cannot run from his flock at the first sign of danger.’ That’s what he went by.”

Three masked assassins who were never identified shot Rother in his rectory in the early hours of July 28, 1981. The Oklahoman had sided with local Indians against the government.

Those who knew Rother remember him as a devoted, humble servant.

“He wouldn’t have cared for all of this stuff,” his brother said of the posthumous recognition. “That’s just not the way he was put together.”

However, Okarche — a town with German roots once known primarily for Eischen’s Bar, the oldest in the state — draws an increasing number of visitors interested in Rother’s story.

A statue outside Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Okarche, Okla., depicts the Rev. Stanley Francis Rother greeting a child. (RNS photo/Keaton Ross)

A statue outside Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Okarche, Okla., depicts the Rev. Stanley Francis Rother greeting a child. (RNS photo/Keaton Ross)

Holy Trinity Catholic Church has even opened a gift shop that sells “Father Stan's Our Man” T-shirts and a biography titled “The Shepherd Who Didn't Run.”

“We’ve got a lot of tourists coming,” said the Rev. John Peter Swaminathan, a missionary priest from India, who serves as Holy Trinity’s pastor.

The Catholic Church says all those in heaven are saints. Canonization is a solemn affirmation by the church to the faithful that a particular person is in heaven and that the person’s life and virtues are especially worthy of emulation and veneration.

To become a saint, a miracle must be verified after his beatification, Coakley explained.

“It will be more than likely a healing of some sort, a miraculous healing,” the Oklahoma City archbishop said. “That could take two years. It could take 200 years.”

Already, though, Catholics in this town cite examples of the slain priest interceding for them.

When Joe Rother’s sister, Sandra Rother McGougan, suffered a brain aneurysm, doctors gave her family a dire prognosis.

“She was about ready to die,” said Joe Rother, a third cousin of the slain priest who joked that he is related to most everybody in town. “They wanted to harvest her organs.”

But then a former parish priest visited Stanley Rother’s grave and requested healing for McGougan. She survived surgery with no brain damage.

A statue of Rother greeting a little girl — based on a photograph from his time in Guatemala — stands outside the Okarche church.

Joe Wittrock, a 65-year-old parish council member who has attended Holy Trinity all his life, said he walks past the statue nearly every morning.

“My mom is dying of cancer right now, so I’m asking for help from him,” Wittrock said. “Not for saving her or whatever — she’s terminal — but just to give her peace.”

About a month and a half ago, lightning struck the church — but damage was minimal.

Did divine intervention occur during an Oklahoma thunderstorm?

“An insurance adjuster went up into the steeple, and there was a burn spot in the bell tower where it caught on fire,” Wittrock said. “The adjuster came down and said, ‘I don’t know who’s looking after your church, but that thing should have burned to the ground.’”

“Father Stan’s Our Man” T-shirts are sold at a gift shop serving the increasing number of tourists coming to Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Okarche, Okla., to learn about the life of slain priest Stanley Francis Rother. (RNS photo/Keaton Ross)

“Father Stan’s Our Man” T-shirts are sold at a gift shop serving the increasing number of tourists coming to Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Okarche, Okla., to learn about the life of slain priest Stanley Francis Rother. (RNS photo/Keaton Ross)