Pope Francis’ decision to invite scholars to dig through the entire archive of papal documents covering the Holocaust, the Second World War, the Cold War and much more “is enormously significant and long overdue,” Ventresca told The Catholic Register in an email.

Ventresca is the author of the 2013 biography Soldier for Christ: The Life of Pius XII. The book won the 2014 Msgr. Harry C. Koenig Award for Catholic Biography. He teaches history at King’s University College at Western University in London, Ont. As one of the world’s leading experts on the life of Pope Pius XII, he’s looking forward to the many ways access to the full archive could deepen his scholarship.

“I do look forward to writing another book, and maybe more, that helps us to understand better this deeply consequential and controversial time in the history of the Church and the world,” he said. “All historical knowledge evolves with access to new documentation.”

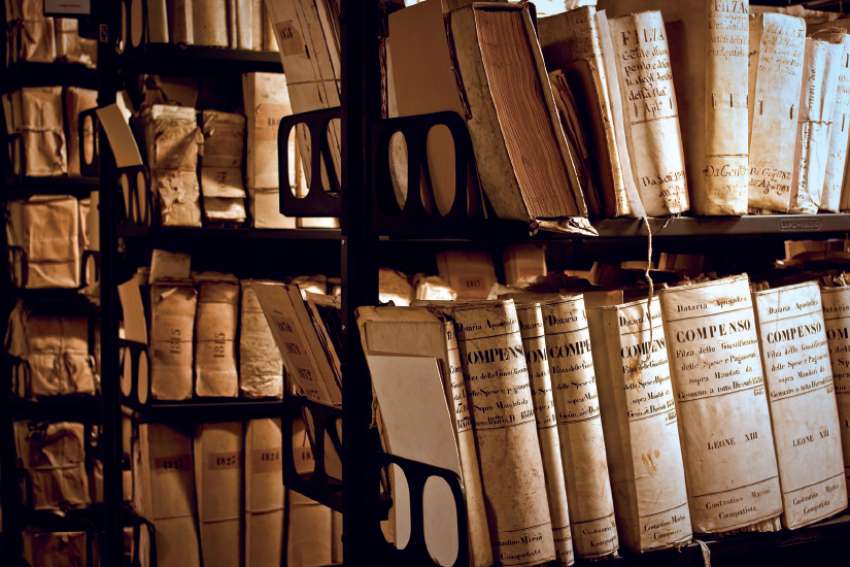

It’s not going to be easy. The archive is so vast it took 20 dedicated archivists more than 12 years to find and organize all the paper spread out over various Vatican offices from the Secretariat of State to the Secret Archives to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. The vast trove required 68 volumes of indexes to account for where the documents are and what they are. There are 538 separate envelopes, with each envelope acting as a guide to the material available on a particular topic or institution.

“I would caution the public to be very suspicious of any rush to judgment and quick-hits that come out in articles and books in the next few years,” said Ventresca. “This is what happened in the 1990s and early 2000s around the unhelpful debates over whether Pius XII was ‘Hitler’s Pope’ or not.”

In 1999 the Vatican invited a team of six Jewish and six Catholic scholars to examine 11 volumes of material relating to the Holocaust. The scholars, including Canadian Holocaust historian Michael Marrus, reached no firm conclusions. By mutual agreement, the academics abandoned the project because of the limitations of only partial access to the archives.

Beginning with the 1963 play The Deputy, a Christian Tragedy by German author Rolf Hochhuth, the actions or inaction of Pope Pius XII during the Holocaust have been intensely debated. That debate got louder with publication of John Cornwell’s biography Hitler’s Pope in 1999. A cause for the wartime pope’s sainthood has been underway since 1965 and Pope Benedict XVI declared him “Venerable” in 2009. At the time, Jewish scholars, including Marrus, urged the Vatican to hold off until historians had a more complete picture and full access to the archives.

“Historians still disagree very substantially,” Marrus told The Catholic Register in 2009. “While saint-making is for Catholics and not for anyone else, we thought it would be wrong to ignore this obvious reality.”

An image of Pope Pius XII as careless or indifferent to the fate of Jews and possibly sympathetic to fascists comes from his role as Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli. Before he became pope, Pacelli negotiated concordats with the fascist regimes in both Italy and Germany. As Pope he met with the fascist president of Croatia. He failed to sign onto the 1942 Allied condemnation of Germany’s program of murdering Jews. He was silent at the expulsion of Rome’s Jews to Nazi concentration camps in German-occupied Poland in 1943. After the war he ordered monasteries and convents not to return Jewish orphans to their Jewish families if they had been baptized while in hiding during the war.

On the other hand, Pacelli was the principal author of Pope Pius XI’s German-language encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge, which was smuggled into Germany in 1937. The encyclical condemned both Naziism and racism. Pave the Way Foundation founder Gary Krupp, a Jewish Knight Commander of the Order of St. Gregory, has long argued that Pius worked behind the scenes to save Jewish lives during the war and that the Pope advanced the cause of Catholic-Jewish relations after the war.

“I don’t expect the archives to yield any great revelation about the war years in particular,” said Ventresca. “Don’t look for the so-called smoking gun that will exculpate or implicate the Pope when it comes to his response to the Nazis and the Holocaust. What the archives will do is to deepen our understanding of the wartime papacy. They will, I believe, sharpen our image of what the Pope did and did not do during the war years and why.”

Ventresca is just as excited about the entirely new material that covers the period between the end of the Second World War and the Pope’s death in 1958.

“The years after the war were also very influential in terms of the history of the papacy and the Church more generally and its place in the modern world,” he said. “Other questions historians have range from the Vatican’s role in and response to the Cold War to the internal dynamics and debates that helped to prepare the way for the epochal transformations of the Second Vatican Council.”

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum director Sara Bloomfield told CNN a full, sober and accurate account of the Vatican’s role during the Holocaust is a matter of urgency.

“This is important for the sake of historical truth, but there is moral urgency too: we owe this to the survivor generation, which is rapidly diminishing,” she said.

There are plenty of questions still hanging, Ontario Jewish Archives archivist Michael Friesen told The Catholic Register in an email.

“Which historical reconstructions, if any, do the archives vindicate?” Friesen asked. “I remember my history professor ripping into John Cornwell’s book Hitler’s Pope and that always stuck with me. So, I would be interested to know if any of the previous reconstructions advanced hold up to scrutiny, now that historians will have complete access to the archives.”

Toronto’s Neuberger Holocaust Education Centre said the Vatican initiative to open up its archives is “warmly welcomed by Holocaust researchers and scholars.”

The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance has a long history of inviting Vatican officials to its academic conferences and in February of 2017 it held a joint conference with the Holy See on refugee policies from 1933 to the present. In October, the organization asked again for the archives to be opened at a meeting with Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s Secretary of State.

“I don’t think the Church should be afraid of history at all,” said Ventresca. “Just the opposite. One of the most profound lessons to be drawn from the lack of transparency around historical abuses, injustices and institutional failures, such as the Holocaust and the sex abuse crisis, is that enormous hurt and harm comes to individuals, communities and to the Church’s own identity and mission when it fails to practice what it preaches. This includes when it fails to practice the Gospel call to know the truth and that the truth shall make us free.”

(NOTE: This article has been updated to clarify that concentration camps in German-occupied Poland during the war were established by the Nazis.)

Support The Catholic Register

Unlike many other news websites, The Catholic Register has never charged readers for access to the news and information on our site. We want to keep our award-winning journalism as widely available as possible. But we need your help.

For more than 125 years, The Register has been a trusted source of faith based journalism. By making even a small donation you help ensure our future as an important voice in the Catholic Church. If you support the mission of Catholic journalism, please donate today. Thank you.