“There were people here before,” she said. “I would like to know something about their history, because it is our history.”

Big city kids, most of them first-generation Canadians, learning about aboriginal culture and history is “sweet music to my ears,” Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner Marie Wilson told The Catholic Register. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada is more than halfway through a process of examining the history and consequences of shipping about 100,000 aboriginal children off to residential schools in the 19th and 20th centuries.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission seeks more government co-operation

- MPs vote unanimously to fulfill Shannen’s dream

- Fatima students witness to Christ in aiding Attawapiskat brethren

The residential schools existed to erase the language and culture from the next aboriginal generation — an effort which has been called cultural genocide. The commission’s goal is to push mainstream Canada into a new relationship with aboriginal Canada.

“It really was in the context of the schools that we got into this mess in the first place,” Wilson said.

It will be up to the schools to forge a new awareness of Canada’s history and its aboriginal people, Wilson said.

“For them (students) to know a full, well-rounded history of Canada — a history of all the founding nations and not just the English and French fact — can only be positive,” she said.

For teachers like Vanessa Pinto, the chance to teach First Nations’ literature is an opportunity to expand her own horizons.

“I’m the Indian with the dot, not the feather kind,” said a grinning Pinto.

Last year she won an award for outstanding professional achievement based on the course she devised for Grade 11 students at Blessed Mother Teresa. She engaged students by arranging Skype conversations and classroom visits with aboriginal authors, took her students to a pow wow in Hamilton and selected all the books used in the course.

She faces a generation of students who read constantly. They read their cellphones, Twitter, text messages, Facebook and advertising screens in shopping malls. To have them understand the written word as literature, as art that comes out of a culture and engages hearts and minds, is an even greater challenge today, she said.

There’s excitement about the course among her students from the Malvern neighbourhood — one known more for gangs and police raids than academics.

“We’re here to learn about the history of our culture,” said Grade 11 student Jed Blancaflor. “In history class we learn mostly about wars and European history.”

“It allows you to get out of your closed mind. It allows you to get out of your ignorance,” said Chowthury.

Outside of the school is a big sign that declares the “virtue of the month.” For February the virtue was courage. The novels students read in Pinto’s class have plenty to say about courage, said Grade 12 student Joan Lootee.

“(Aboriginal people) had to be courageous,” she said. “It was our government that basically persecuted them.”

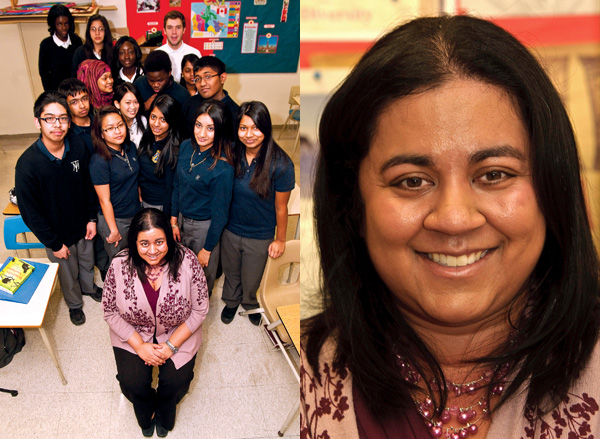

Vanessa Pinto’s Grade 11 students at Toronto’s Blessed Mother Teresa High School are embracing the opportunity to learn about aboriginal culture. "It allows you to get out of your closed mind," said student Radiyah Chowthury.

Photo by Michael Swan

Pinto’s students seem to get something retired gym teacher Brian Armstrong sweated, preached and campaigned for over the last decade of his career in Toronto’s Catholic schools. Armstrong teamed up with then Lieutenant Governor James Bartelman to get books in the hands of aboriginal kids through book drives in Toronto schools starting in 2003. At the same time, Armstrong was trying to make kids aware of the aboriginal culture of Canada.

“We want to move the children’s idea that there is another culture outside of Toronto. It’s outside of Toronto and it’s Canadian,” he said.

Armstrong organized the first Northern Spirit Games in the Toronto Catholic District School Board in 2004. Though retired, he continues to help run the games that this year brought over 300 students together on five different February days to learn about aboriginal traditions in sport — games like the one-foot high kick, blanket toss and snake races.

Nobody would claim one day spent trying out these traditional games amounts to an education in the culture, said Brebeuf College gym teacher Nik Galateanos. But it may spark something.

“We’re creating a bit of awareness,” he said.

Awareness is not trivial, said Metis drummer and education consultant John Somosi.

“The change for the kids up north, it has to start with a change for the kids down here,” he said.

John Somosi is part of a group that holds cultural workshops at schools across southern Ontario.

Photo by Michael Swan

Somosi and Kathryn Edgecombe together form Sky Buffalo. They run cultural workshops at schools across southern Ontario teaching kids about the real people they may know only through movies and negative stereotypes.

“To have some understanding of a culture striving to survive is a big deal,” said Edgecombe.

The Grade 9 art students at Fr. Redmond are starting to understand that art is about survival. For people who have faced cultural genocide every painting, print and sculpture is another breath drawn, another heartbeat into the future.

“It’s about respect,” said Grade 9 student Nicole Shea.

“We’re not being ignorant to this other culture,” said her classmate Coriana Dinucci. “We’re learning about it and we’re respecting it.”

Their teacher, Robert Comella, loves the fact that these kids are starting to perceive art in the context of culture.

“It (aboriginal art) is part of the land that we live in. This is where we live and the culture we live in,” he said. “This is art from the true north. It’s Canadian.”

The connection between the big city kids and aboriginal culture is getting a boost from Ontario’s Ministry of Education. There’s extra funding available for native studies courses. Where a board normally couldn’t run a class with less than 12 students, the funding for this program allows boards to assign a teacher for as few as eight students.

But it’s not without glitches. Unless the board can substitute the native studies courses for core curriculum courses — as with Pinto’s English class — they become optional extra credits.

“Those are additional to curriculum, therefore it’s almost impossible for the students to take those courses and still fulfill their graduation requirements,” said board program co-ordinator Vince Citriniti.

There’s a Grade 11 law course that looks at treaties, a Grade 10 history course and an aboriginal beliefs and culture unit that fits into Grade 11 religion.

Grade 9 Fr. John Redmond Catholic Secondary students Illia Nikulchuck, Jacinta Judge and Roman Makuch, above, work with woodland style native images in their art class. Makuch thinks of his art classes as lessons in Canadian culture.

Photo by Michael Swan

The chances of an aboriginal student taking these courses is minimal. There are only 128 self-identified aboriginal students in Toronto’s Catholic schools, out of a total student body of 93,000. Only 34 of those students are in high school. Though it’s likely there are more who have declined the opportunity to identify themselves, census numbers show the probable total aboriginal population in Toronto Catholic schools at about 400.

In Toronto, aboriginal education is primarily about expanding the vision of non-aboriginal students. But it’s also about the Catholic school mission of teaching toward social justice. That’s why Toronto Catholic teachers and administrators have been involved in helping the school in Attiwapiskat over the last 10 years, said Citriniti.

“I’ve been up there,” he said. “Over the years we’ve gone to the Great Moon Festival for teacher materials. We’ve had book exchanges.”

Last year every school got a copy of a DVD of Shannen Koostachin speaking to Toronto Catholic students about how aboriginal kids dream of schools like theirs. Fifteen-year-old Koostachin from Attiwapiskat gave that speech several times before she was killed in a 2010 car accident. Her determination to improve education for aboriginal children spawned the Shannen’s Dream foundation — a cause that’s been championed in Catholic schools across the city.

Nestled up near Georgian Bay and spreading across Central Ontario, the Simcoe-Muskoka Catholic District School Board has a more substantial aboriginal reality in its classrooms. There are 350 aboriginal kids out of 21,000 students in its schools. The board is determined that those kids never feel like strangers in their classrooms, said Linda McGregor, manager of First Nation, Metis and Inuit education initiatives for Simcoe-Muskoka Catholic.

McGregor teamed up with the Chigamik Community Health Centre in Midland, Ont., and the Simcoe County Children’s Aid Society to produce a pocket guide to aboriginal culture aimed at teachers. The board has also developed a system of “champion teachers” who work on aboriginal programming in every school.

As a Mohawk, McGregor believes education is an important element in reconciliation.

“Reconciliation is its own process. We’re in the education piece,” she said. “Education and knowledge is healing. The more information we have, the more understanding we have. That in itself is healing.”

Though he started the class telling this reporter his art class was not some bird course — not an easy pass — by the end of the class Makuch had a different take.

“If you’re really committed to this, it’s not hard.”