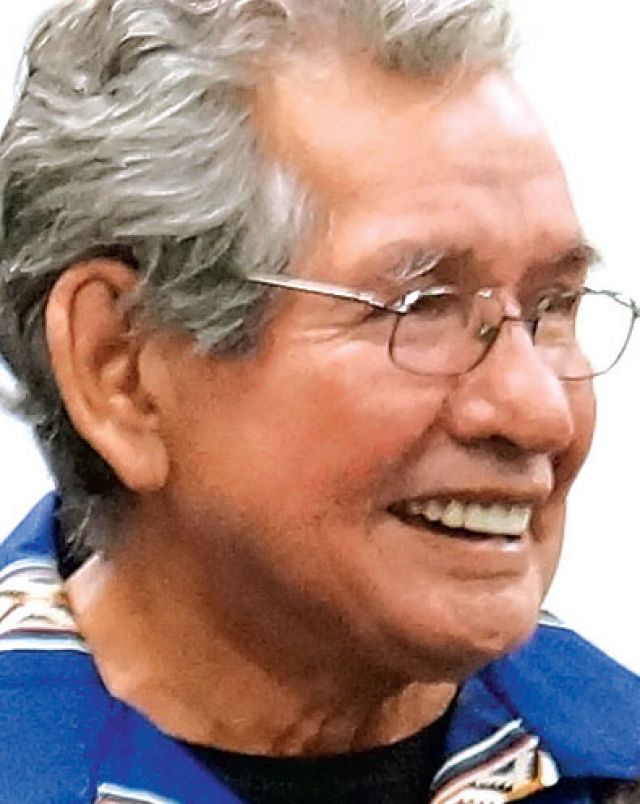

“History was telling me I was not a great person,” said the founder and executive director of the Ottawa-based Kateri Native Ministry.

“I didn’t want to be Indian. There was too much hurt. I hid for many years through alcohol and drugs.”

In a Catholic setting, God’s grace touched Corston’s life and delivered him from his addictions and opened his heart and mind to the Gospel.

“I was happy in that world as a Christian, but deep inside something was missing,” he said. “I didn’t know what it was.”

The grace of God helped Corston make the connection to his nativeness, helping him become “stronger and stronger.”

Corston was living in Montreal when he began to sense God telling him, “John, I want you to pray for native people.” So Corston began to travel in remote communities, preaching the Word of God and praying for healing. He found many communities had no church services at all, with only occasional visits from a priest, if at all, and a scarcity of religious brothers and sisters as well.

Corston’s travels over the past 15 years developed contacts in many First Nations communities for native leaders who might be able to step in to lead their Catholic communities with a little formation. When he visited he found people are ready to move on from the hurt of the residential schools, to heal.

“I believe the Church is open to respecting our cultures, respecting our ways,” said Corston. “Many are still testing the waters. There are still some problems with culture but slowly its beginning to heal.”

Saint Paul University, in conjunction with Kateri Native Ministry, recently offered an accredited Aboriginal Pastoral Ministry Leadership Program. It gave 24 participants from First Nations and Inuit communities from across Canada a “micro-seminary” formation in liturgy, the preparation of homilies and the proper way to proclaim the Word of God if they must preside at a service in the absence of a priest, said Fr. Bill Burke, the Canadian of Conference of Catholic Bishops’ national liturgy director.

Participants are “on the frontlines of where the spiritual culture of the aboriginal people of Canada and the spiritual culture of the Latin Church are intersecting,” said Burke. While the course aimed to give them the tools of leadership, Burke said he and other faculty “have much to learn.”

Saint Paul University theology professor Susan Roll has been involved in the program since its very beginning when she and another woman tried to organize a one-day training workshop several years ago.

“We discovered it was impossible to teach presiding skills for a Sunday celebration of the Liturgy of the Word in just one day,” she said, so last year, the university launched a week-long pilot program.

This year, the program was up and running, and included Ottawa Archbishop Terrence Prendergast on the faculty, teaching an overview of Scripture.

Irvin Sarazin, an Algonquin from the Golden Lake First Nations in Ontario, acted as elder for the program. He appreciated learning about all the hard work that goes into preparation of a homily. He also came to realize that not only is the distribution of Holy Communion sacred, but so is proclaiming the Word of God in Scripture.

“When we’re up there, Jesus is speaking through us,” he said.

Donna Naughton of Ojibway of the Pick River First Nation acted as the facilitator this year.

“The week has brought renewal for some; an encouragement and a hope for others. And it has created a knowledge base of the sacredness of bringing the Word to others in their communities,” she said.

Lina Desmoulins, also of Pick River, said she had lost her Ojibway language after missionaries discouraged using it. Her grandmother used to lead church services back in the days when the priest could not come, so she came to learn how to do the same thing.