Three years after the Christian Brothers of Ireland filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the United States, 422 survivors of abuse at schools and orphanages operated by the brothers will begin receiving cheques this month. Included among them will be 90 former Newfoundland victims from the 1950s and ‘60s.

The claimants will each receive a share of $16.5 million left from the sale of Christian Brothers assets in the U.S. The cheques will begin at $5,000 and average around $39,000.

Though that’s the end of the saga in the United States, the Canadian victims — most from Mt. Cashel but about half-a-dozen from Newfoundland day schools the Irish Christian Brothers operated — are pursuing their claims against the Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation of St. John’s.

As the Church and victims await another day in court, the Archdiocese of St. John’s is preparing to mark the 25th anniversary of the Winter Commission — an enquiry set up in 1989 by then Archbishop Alphonsus Ligouri Penney. The commission found the archbishop had known about and not reported sexual abuse in the Archdiocese of St. John’s and that archdiocesan officials participated in the suppression of a 1975 police investigation. It’s final report led to Penney’s resignation and to years of soul searching and waves of child protection regulations from Canada’s Catholic bishops beginning with “From Pain to Hope” in 1992.

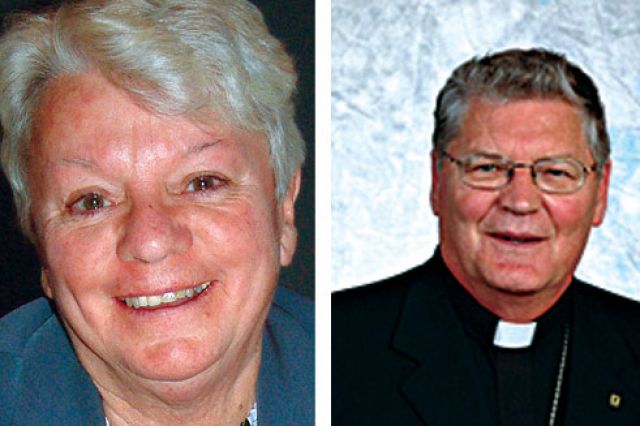

Sr. Nuala Kenny, a professor of pediatrics and bioethics who sat on the Winter Commission, will lead free sessions for laity March 21 and 22 at Corpus Christi Parish in St. John’s. She will also speak with all St. John’s clergy in a separate session.

Since 1990 lawyer Geoff Budden, a partner at Budden, Morris LLP, has spent virtually his entire career representing abuse victims, beginning with a single Mt. Cashel victim in the first Mt. Cashel court case. He understands the surprise people express over the idea Mt. Cashel is still being litigated.

“While it’s true that the litigation began in 1990, it’s not true that any one person has been litigating their claim for over 20 years. It’s really a series of lawsuits,” Budden told The Catholic Register.

The Canadian province to the Irish Christian Brothers went bankrupt in 1996. It’s assets were divided and combined with a settlement offer with the provincial government. The $11.5 million settlement was divided between a group of victims who were mainly resident at Mt. Cashel in the 1970s.

The generation of victims from the 1950s and ‘60s can no longer sue the Irish Christian Brothers in Canada, but believe they have a legitimate claim against the Archdiocese of St. John’s.

“We say the bishop had actual knowledge that children were being abused at Mt. Cashel; that St. Raphael’s Parish, or rather that the orphanage and St. Raphael’s Parish, existed within the same building,” said Budden. “There were diocesan priests on duty.”

Budden also asserts that the archbishop (it was a bishop before 1955) can be held accountable because the brothers operated in the archdiocese according to standards “that were zealously insisted on by the archbishop or bishop with regard to reporting who was stationed within the archdiocese and so on.”

Archbishop Martin William Currie rejects the notion that the archdiocese was liable for what the Christian Brothers of Ireland did.

“The Irish Christian Brothers are a distinct corporation with a distinct identity,” Currie said.

The archdiocese neither appointed nor supervised the Christian brothers who were running their own institutions, he said.

“I can’t see why we should be responsible for a religious order who appointed their own people and supervised their own people,” said Currie.

Currie also doubts that the mere fact religious orders tell the archbishop about appointments before making them means that the archdiocese had some responsibility for their actions.

Currie concedes that few people are likely to see why the archdiocese is still fighting in court against Mt. Cashel victims.

“People don’t make the distinction between them (the Christian Brothers) as a separate corporation in the archdiocese,” Currie said. “What responsibility does the archdiocese have for it? That I don’t know. Our lawyers tell us they don’t think we have.”

Currie is the fourth archbishop of St. John’s to find himself saddled with the legacy of Mt. Cashel.

“I can’t say when this will go away. I pray, but prayer doesn’t work like that. I know throwing money at it doesn’t work. What do you do?” Currie asked. “All of a sudden somebody comes out of the woodwork and says something happened in 1953. What are we supposed to do?”

The archdiocese continues to pay for counselling for many of the original victims of Mt. Cashel who are now spread across Canada.

“I’m not sure it will ever go away,” said Currie.