Her maternal great-grand-parents fled Iraq for Russia when the Young Turks were slaughtering Assyrian Christians and Armenians in 1915. The 20th century’s first genocide was a side effect of the attempt to carve a modern, secular state out of the dying Ottoman Empire during the First World War.

Now the Assyrians and other Christians are on the run from an attempt to refound an Islamic empire out of the ruins of Syria and Iraq, two failed modern states. Inspired by a book called The Management of Savagery, the Islamic State and its self-appointed caliph has forced up to half a million people, including more than 100,000 Iraqi Christians, on the road searching for safety.

Eventually the Kyorkis family returned from Russia to the southern Iraqi city of Basra, where, by the time Sherly was born in 1990, they were urban, middle class, educated citizens of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. They lived in peace with their Sunni and Shia Muslim neighbours. But the 1993 Gulf War sent the family again searching for safety — this time to Canada.

As president of the Assyrian Chaldean Syriac Student Union in Canada, Sherly Kyorkis is now pleading for Canadian intervention to protect the aboriginal people of Iraq.

Syriac and Aramaic-speaking people were the first Iraqis and they were among the very first non-Jews to embrace Christianity. They built churches on the plain of Nineveh as early as 80 years after the birth of Christ, centuries before Arabs swept into the region with Islam.

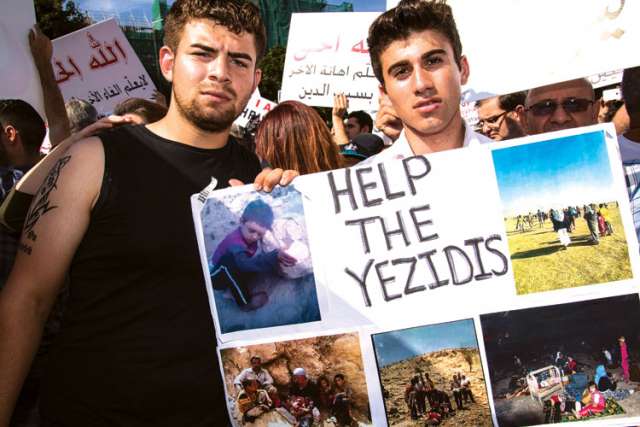

With those indigenous Iraqis now threatened with ethnic and religious cleansing by Sunni militants of the Islamic State, Kyorkis helped to organize a protest of about 5,000 Iraqi immigrants and sympathetic Christians at Queen’s Park in Toronto Aug. 10.

“We never dismiss the fact that Iraq is our land and we are Iraqi people, but when it comes down to our ethnicity, ethnically we’re not Arab. We’re indigenous to that land and we’re the descendants of Mesopotamian people,” Kyorkis told The Catholic Register. “We can’t let that go in order to conform to what Iraq is now.”

Among the protesters at Queen’s Park were Yazidis with relatives trapped on Mount Sinjar, dependent on American air drops for food and water. While the dramatic story of the tiny Yazidi, Mandaean and Sabean minorities has attracted most of the media attention, the majority of protesters at Queen’s Park and the largest group of people on the run in Iraq are Christians, two thirds of them Chaldean Catholics.

The ancient Syriac Orthodox, Syriac Catholic and Assyrian Church of the East are also seeing crosses pulled down from their churches and their people threatened — “Convert or die.”

Of course Shia Muslims and others who disagree with the Islamic State are also threatened.

The Islamic State (also known as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) controls a cross-border area of Iraq and Syria that has been variously estimated to be the size of Belgium to the size of Great Britain.

Iraq’s 150,000 remaining Christians are all either internally displaced or already refugees in Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and Kurdistan. Even with Kurdish Peshmerga forces battling for control of Mosul Dam — with the help of American bombing — Iraq’s second city remains cleansed of Christians.

The Vatican has called on the international community to protect the remaining Christians of Iraq in the plain of Nineveh, north of Baghdad.

“The tragic experiences of the 20th century and the most basic understanding of human dignity compels the international community, particularly through the norms and mechanisms of international law, to do all that it can to stop and to prevent further systemic violence against ethnic and religious minorities,” Pope Francis wrote to United Nations secretary general Ban Ki-moon on Aug. 9.

The responsibility to protect vulnerable minorities lies with Western governments and the churches. Protesters at Queen’s Park made three key demands of the Canadian government:

- speed up the refugee process for Iraqis who need to be resettled;

- treat internally displaced Iraqis as refugees instead of forcing them to cross an international border before they are considered for resettlement;

- pressure the United Nations to create a zone of protection for Iraqi Christians on the Plain of Nineveh.

The demand for a safe haven is also coming from the Vatican. The pope’s personal representative to the Christians in Iraq, Cardinal Fernando Filoni who has been in the country since Aug. 13, teamed up with Chaldean Catholic Patriarch Louis Sako of Baghdad to demand international action to guarantee the Christian community’s survival in Iraq.

Iraqi Canadians worry that the rest of us are skimming over Iraq headlines. The purpose of the silent march of 5,000 through downtown Toronto was to draw attention to the crisis, said refugee advocate and protest organizer Rabea Allos.

“They don’t have water, they don’t have food, they don’t have shelter. Originally they were staying at the homes of relatives or at schools, monasteries, churches. Now they’re staying outdoors. They need food, they need mattresses, blankets. We would like to see that the Canadian government helps,” Allos said.

Beyond short-term humanitarian relief, Canada needs to resettle Iraqis faster and more efficiently, he said.

“Applications are being delayed at Winnipeg for six months,” said Allos.

Many of the protesters and some Canadian bishops have asked that Muslim leaders issue fatwas against the Islamic State and clearly condemn ethnic cleansing in Iraq. But Canadian imams long ago stated their condemnation of violence in the name of religion, said Toronto Imam Habeeb Alli.

“Muslims are always put in the jury box every time some fanatic raises his voice,” he said. “Yes, our hearts bleed when someone is suffering or injustice is done somewhere. But it doesn’t necessarily mean that we have to condemn, or go on television, or give fatwas about everything.”

The Islamic State is hardly waiting for approval from Canadian Muslims, so issuing a fatwa from Toronto would be an empty gesture, Alli said. Canadian Muslims have chosen a modern, pluralist and democratic state and want nothing to do with some pretend caliphate enforced at the end of a gun.

“That someone can just rise up like this and say they are the leader of the Islamic world, this is un-Islamic and it’s illogical,” said Habeeb. “The ulama (religious scholars) of the Islamic world, including of the Western world, of England, the United States and the Canadian Council of Imams, they have condemned this approach by this Abu Bakr.”

Ibrahim Awad Ibrahim al-Badry has changed his name to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and appointed himself caliph of the Islamic State. He has rallied fighters, first against the Assad regime in Syria and then to fight on behalf of the Sunnis of Iraq — a group largely excluded from government since the fall of Saddam Hussein 10 years ago. Abu Bakr’s program is taken from a text that has floated around the Internet for years called The Man-agement of Savagery.

“If we succeed in the management of this savagery, that stage (by the permission of God) will be a bridge to the Islamic state which has been awaited since the fall of the caliphate,” reads the short book. “If we fail — we seek refuge with God from that — it does not mean the end of the matter; rather, this failure will lead to an increase in savagery!”

Canadian Christians are re-sponding to this with charity. At Aug. 18 Masses, Toronto parishes held a special collection for the Catholic Near East Welfare Association of Canada. The CNEWA will feed that money directly to Chaldean, Syriac Orthodox and Syriac Catholic bishops. A lot of the focus is on people sleeping in the streets of the Kurdish capital of Erbil.

“It’s a big city, but of course not ready to welcome 80,000 people,” said CNEWA Canada executive director Carl Hetu.

The Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace has already sent an initial contribution of $50,000 to the Caritas network in Iraq, Turkey and Lebanon. Development and Peace is the Canadian arm of Caritas. The Vatican-affiliated network is caring for 3,200 Iraqi families with food, shelter and psychological support.

Aid to the Church in Need sends its contributions to the Catholic and Orthodox bishops of Iraq. “The bishops are working with us to determine the priorities,” said Aid to the Church in Need Canada executive director Marie Claude Lalonde. In fact CNEWA, Caritas, the Jesuit Refugee Service and Aid to the Church in Need are all working together, Lalonde said.

“It’s the risk that Christianity will totally disappear from the place,” she said.

Malteser International, the relief agency of the Knights of Malta, has run a health care centre in Karamlish, 430 kilometres north of Baghdad, for years. The clinic shut down when Islamic State forces overran the town. The Sovereign Order of Malta has put up a $500,000 matching pledge to spur contributions from North America.

“Helping the sick, the wounded and those fleeing persecution in the Middle East was the order’s original mission 900 years ago, so the current plight of Iraqi Christians and minorities has moved us deeply, said Malteser International Americas executive director Ravi Tripptrap in a release. “We are doing everything in our power to bring immediate relief to those in need and ensure their survival.”

From Hamilton’s St. Thomas the Apostle Chaldean Catholic Church, Fr. Niaz Toma looks back in shock and disbelief at his home town of Erbil. Toma fled Erbil in 2002 when he felt his life was in danger. As he pastors Chaldean Catholics in Hamilton and Oakville, he can’t believe that the world around him calmly goes on.

“We were so surprised and shocked by the world silence,” Toma told The Catholic Register’s Evan Boudreau. “This is not persecution actually. This is a genocide. When one expels a people of 2,000 years and destroys their churches and burns their monasteries and burns some of the priceless treasures… We have books, hand written books, that go back to centuries ago. All of these books were burned.”