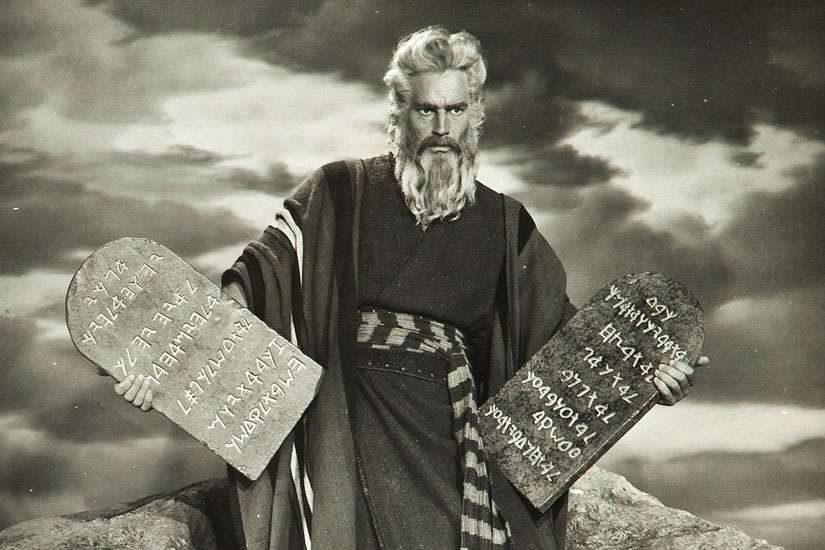

Take for instance our feelings about the Ten Commandments found in the Book of Exodus (20:1-17) and Deuteronomy (5:1-32). Unsurprisingly, almost three-quarters of us (73 per cent) think the Ten Commandments still apply today. But more surprisingly, that includes more than half (54 per cent) of Canadians who reject religion.

“I found that really interesting,” said Justin Trottier, atheist spokesman for the Canadian Secular Alliance. “Half of the commandments involve belief in God — how to worship God. I wonder if those people know what the Ten Commandments are. If you reject religion, you’ve rejected half the commandments.”

Chances are Canadians think the world would be better if we didn’t steal or kill or covet. And a little respect for parents and grandparents and people in general would be a good idea. The survey didn’t ask them to actually list all Ten Commandments.

Strangely, the same people who like the idea of the Ten Commandments — which are, after all, commandments and not suggestions — are ambivalent about any list of definite, objectively true statements about right and wrong.

A majority (51 per cent) of Canadians agreed with the statement, “What’s right or wrong is a matter of personal opinion.”

This came right after the question about the Ten Commandments.

A solid 40 per cent of Canadians inclined to accept religion agreed that right and wrong is a matter of opinion, and 53 per cent of those inclined to reject religion thought so. But the most relativistic among us were those Angus Reid classed as ambivalent toward religion. Fifty-seven per cent of this group think of right and wrong as just your opinion.

The Angus Reid Institute survey divided Canadians into these three categories. Those who embrace religion came in at 30 per cent of us. Those inclined to reject religion are 26 per cent. The ambivalent crowd is the largest number at 44 per cent of Canadians.

The moral relativism of Canadians, at least for the 38.7 per cent of us who are Catholic, probably has more to do with our attitudes about religious authority figures likely to make hard, dogmatic statements about precisely what is right or wrong, said Julius-Kei Kato, King’s University College professor of religious studies.

“A great many Catholics still self-identify as Catholic yet may disagree with some official Catholic teachings and with what the authorities tell them to accept,” Kato wrote in an e-mail from the King’s campus at Western University in London, Ont. “This phenomenon is evidenced throughout Catholic history, but in recent history it is clearly the result of a number of factors among which the following are arguably the most significant — the sweeping revolutionary sociological changes that happened in Western societies, such as the sexual revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, the widespread disagreement of lay Catholics in the West with some official Catholic positions insisted upon by successive popes from Paul VI to Benedict XVI on artificial contraception and the possibility of ordaining women.”

On sex in particular, the clergy sex abuse scandals that have hit the faithful over and over since the Mount Cashel Orphanage abuses came to light in 1989 have left many less inclined to accept clerical judgments about the rights and wrongs of sex, said Kei.

“These things practically destroyed the moral credibility of the Catholic leadership for many,” he said.

In this atmosphere it is perhaps unsurprising that Catholic positions on specific moral controversies don’t find much agreement among the Canadian public.

The Angus Reid study found 85 per cent of Canadians approve and accept “a woman being able to obtain a legal abortion if her own health is seriously endangered by the pregnancy.” Another 11 per cent disapprove but still accept the idea. Only four per cent both disapprove and do not accept it.

Among those inclined to accept religion, the numbers are only slightly more anti-abortion. Sixty-nine per cent of the embrace religion group approves and accepts, 22 per cent disapprove but accept and nine per cent both disapprove and do not accept.

A bare majority (51 per cent) of Canadians approve and accept the idea a woman should be able to obtain a legal abortion for any reason — though that number falls to 28 per cent for the embrace religion crowd, as opposed to 72 per cent of those who reject religion.

On gay couples adopting children, 60 per cent of Canadians approve and accept, including 40 per cent of those who embrace religion. Sixty-three per cent of Canadians approve and accept same-sex marriage, including 41 per cent of those who embrace religion.

Canadian sexual mores are more squeamish on the question of children under 18 having sex. Only 36 per cent of all Canadians approve and accept sex below the voting age and that drops to 18 per cent of those who embrace religion.

As for unmarried adults having children, there’s a big gap between Canadians in general and those of us inclined to embrace religion. While 70 per cent of the population in general approves and accepts procreation among the unmarried, that falls to 44 per cent among those who embrace religion.

On moral questions that don’t involve sex, Canadians find more common ground.

More than half of Canadians (57 per cent) don’t see a justification for war even when other ways of settling international disputes fail. That result is consistent for Canadians who embrace religion (57 per cent), reject religion (57 per cent) and the ambivalent (58 per cent).

Do the poor have a right to an adequate income? Eighty-six per cent of Canadians think so, including 89 per cent of those inclined to embrace religion.

The gap between religious and non-religious Canadians reappears on the question of euthanasia. Asked whether they agree or disagree with the statement, “There are some circumstances in which a doctor would be justified in ending a patient’s life,” 61 per cent of those inclined to embrace religion agree, compared to 92 per cent of those who reject religion and 86 per cent of the ambivalent.

Who volunteers? This survey like many others finds it’s the religious. Forty-five per cent of those who embrace religion said they had volunteered in the last month, compared to 27 per cent of those inclined to reject religion.

The Angus Reid Institute study collected answers online from 3,041 Canadians between March 4-11. The respondents were part of Angus Reid’s panel of 140,000 people who have previously told the organization they are open to completing polls. The weighted survey results are accurate within a margin of error of plus or minus 1.8 per cent 19 times out of 20.