“The next day he was killed.”

The day remembered so vividly by Mazzerolle was June 22, 1965, the day Fr. Art MacKinnon was murdered. To many, the young priest from Cape Breton died a martyr’s death for defending the weak and vulnerable during a bloody civil war.

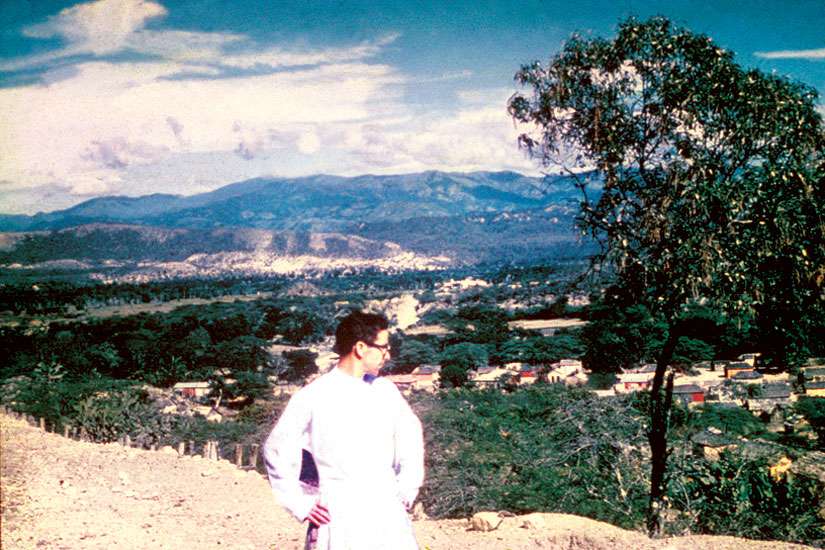

Just hearing MacKinnon’s name 50 years later brings back images, sounds and smells from the small town of San José de Ocoa in the Dominican Republic, where Mazzerolle worked with the Scarboro Foreign Missions priest all those years ago.

“Father was so good,” said the 95-year-old member of the Religious Hospitallers of St. Joseph. “He was there with the young people, taking them in and helping the young people.”

It was solidarity with those young people that cost MacKinnon his life.

Ordained in 1959 at age 27, MacKinnon arrived in a small parish in the Dominican Republic in 1960. He went to work, easing the suffering of the oppressed Dominican people then ruled by dictator Rafael Trujillo. MacKinnon’s first tasks were to help build a school, an old age home and to learn Spanish.

“I went there to work with him because he was working in San José de Ocoa and the Scarboro Missions said they needed some help,” said Mazzerolle, who spent most of her 70 years as a nun working with the poor. “After one of the priests in (Monte Plata) went home they asked Art to go and work there.”

That April, 22,000 American troops arrived on the island as tension between the ruling class and the working people erupted into war. Missionaries like MacKinnon, who were aligned with the poor, became easy targets for the military.

“Despite the dangers, Fr. Art continued to denounce the brutality,” said Fr. Gerald Curry, a Scarboro Foreign Missions priest who went to the seminary with MacKinnon in the 1950s.

“He witnessed the people’s tears as he celebrated the Eucharist and spoke of Jesus who stood up for the persecuted. He helped them realize their rights and dignity as human begins.”

MacKinnon led a delegation on June 14, 1965 to demand the release of 37 parish youth who had been imprisoned without cause. The government had been waging a campaign of terror, and MacKinnon used his pulpit to denounce the oppression.

On June 22, two men came to the priest’s house and pleaded with MacKinnon to come with them to the home of a sick person. Despite warnings, including words from his superior to avoid venturing out at night, MacKinnon answered the call for help.

He never returned. He was shot at the side of a road.

There were no witnesses to the shooting. Years later, MacKinnon’s nephew conducted his own investigation and wrote a book in which he concluded the crime was probably committed by two policemen who were working with the military. Both policemen were shot and killed by a solider that same night.

“He went in his jeep and that is when he was shot,” recalls Mazzerolle. “We were all upset. I was scared . . . because we had soldiers come stay outside our house all day long and all night; two at the front door and two at the back.”

A monument still stands at the roadside where the young priest was murdered.

“Fr. Art’s death was the result of his love for the people of his parish,” Curry recently wrote. “Because of his solidarity with them, he came to share their suffering even to the sacrifice of his young life.”

Mazzerolle isn’t the only one remembering MacKinnon on the 50th anniversary of his death.

On June 21 in the small township of New Waterford, N.S., where MacKinnon spent his boyhood, Antigonish Bishop Brian Dunn will celebrate Mass for MacKinnon at the parish of St. Leonard. Many of MacKinnon’s relatives will be in attendance to remember the martyr’s life, and to see a portrait of MacKinnon “enshrined” at St. Leonard’s, Curry said.

Curry, who helped organize the celebration in Cape Breton, said he is glad MacKinnon’s sacrifice is being acknowledged.

“I’m very glad that we are not forgetting Art because Art gave his life in sacrifice for his brothers and sisters in the Dominican Republic,” he said. “He followed in Christ’s footsteps in a very real way.

“I’m so glad that we are celebrating what Art did.”

Today in the Dominican parish of Ocoa, the Padre Arturo Centre carries on MacKinnon’s work in a facility that houses an elementary school for children and teaches carpentry and sewing to adults. Mazzerolle says the centre’s success is due to the prayers and intercession of its namesake, Fr. Padre Arturo.

When she was still in the Dominican, Mazzerolle would light a small candle each day and place it beneath a picture of MacKinnon. During hard times, he was always there for them, she would say.

“Whenever things are at their most desperate, something always comes up — thanks to him.”

MacKinnon is buried in Monte Plata where, says Curry, many people who were not even born when he died continue to celebrate his life.