This newspaper first reported the shortfall in January of this year, but a Globe and Mail report that hit the front page April 19 has raised accusations that the 50 Catholic organizations party to the 2006 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement used legal trickery to sidestep their obligations.

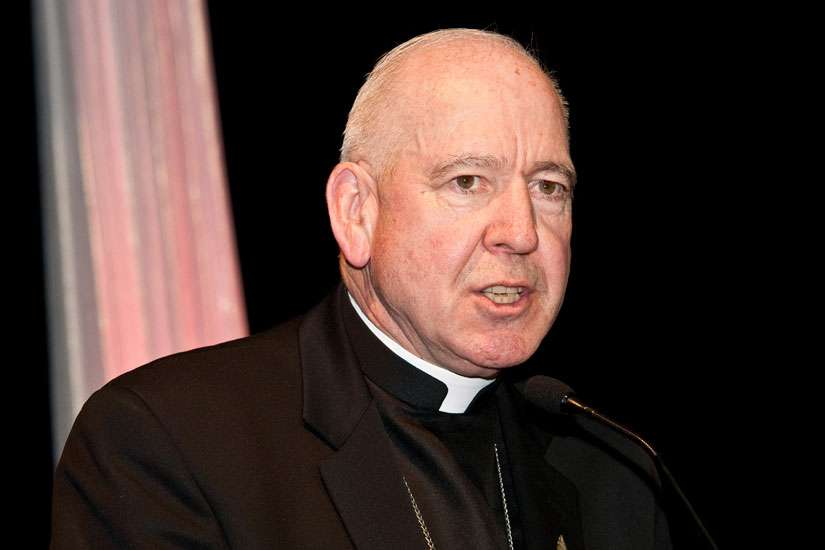

“It isn’t accurate,” said Pettipas, who chairs the board of 50 Catholic Entities who are party to the settlement. “There was a cash contribution.

There was in-kind payment. There was a best-efforts campaign. We did all those. There wasn’t any weaselling out.”

As the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was pending last year there was a disagreement between the federal government and Catholic lawyers over whether or not the Catholic Entities had fully paid the last $16.6 million of $29 million owing in cash contributions to healing programs that would be run by First Nations organizations. The government contended the Catholic entities had paid $15 million and still owed a final $1.6 million.

All sides were seeking to conclude the settlement before the TRC issued its final report.

The contested $1.6-million payment went to arbitration before Justice Neil Gabrielson in Saskatchewan. He ruled in July last year that the Catholic Entities owed another $1.2 million and that this payment would conclude all the Catholic obligations under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

“So, from our 50 Catholic Entities, we made another cash call,” said Pettipas. “We had to do it before the end of the TRC mandate, so we paid $1.2 million… We said, here’s $1.2 million and we get our release.”

While no one is disputing the final cash settlement, the glaring shortfall in the fundraising campaign has led some to question whether the Catholic Entities should have been released from their obligations.

Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennett said the government would pressure the Church into restarting its fundraising efforts.

“I think we want to explain to the Catholic Church that we’re serious about them honouring this obligation and we will apply deeper pressure,” Bennett told The Globe and Mail.

The original 2006 agreement did not commit the Catholic Entities to anything more than “best efforts.” Former Assembly of First Nations Chief Phil Fontaine, a residential school survivor who chaired the Moving Forward Campaign for the Catholic Entities, believes best efforts were made to raise as much money as possible.

“We tried very hard to meet the commitment that the Catholic Church Entities faced. We were unsuccessful,” Fontaine told The Globe and Mail.

Ketchum Philanthropy senior vice president Joanne Villemaire told The Catholic Register the campaign was “disappointing” but that every effort was made against some very bad odds.

“This was a very tough project, a tough project going in,” Villemaire said. “There was significant effort that was put into it. Everyone took it seriously.”

Even before Ketchum took on the project, the fundraising professionals advised the Catholic Entities board it would be a tough slog. Ketchum is one of Canada’s largest fundraising organizations whose client list includes every major hospital and university in the country and extends to organizing United Way appeals across Canada. While the seven-year Moving Forward campaign did manage to raise money from Catholic dioceses, religious orders and associations, neither wealthy individuals nor corporations were ready to step up and become lead donors, said Villemaire.

“A lot of people had given an indication that they would be at the table, but at the end of the day it was very low levels or it was not there,” she said.

Many Canadians find it difficult to understand where the Indian Residential Schools fit into the complex history of colonization that has marginalized and oppressed aboriginal Canadians over the last four centuries. At least half of Canada’s Catholics arrived as immigrants over the last 50 years. Many have trouble seeing the 150-year history of the residential schools as their fault.

“It’s not necessarily that Canadians are not supporting this. I think they’re probably saying this is a government issue and government should probably be supporting this. It’s a government responsibility,” said Villemaire. “The Catholic Church and other religious entities have been brought into this because they were all part of delivering the services on behalf of government.”

Ketchum and the Catholic Entities decided to part ways on the campaign in 2013.

“We dismissed them,” said Pettipas. “Not because they were doing a bad job. They were doing a terrific job, but it wasn’t working. We were spending more money doing administration and promotion than we were taking in. On a $25-million campaign, you can expect to spend 10 per cent or $2.5 million on all that. But we had already spent $2 million and got almost nothing. So what do you do? Do you keep spending that kind of money and go broke yourself? What would you do?”

With the departure of Ketchum, the Catholic Entities decided to launch a nationwide pew collection. Some dioceses decided to give a lump sum rather than distribute envelopes, but most participated. However, a week before the envelopes landed in pews Typhoon Haiyan, one of the strongest tropical cyclones ever recorded, hit the Philippines.

“The needs or the plight of Canadian aboriginals sort of paled in comparison to the immediacy of that one,” said Pettipas.

The final tally on the pew collection was just shy of $1 million.

As for the moral obligation of reconciliation, the Church is still there in remote aboriginal communities doing all that it can, said the archbishop. In fact, the Catholic Entities have over-fulfilled their obligation for in-kind services under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement. Where the court had ordered $25 million in services to be delivered between 2007 and 2017, the Catholic Entities had spent nearly $30 million on community-based projects and services within just seven years.

“I think reconciliation is about relationship,” Pettipas said. “It’s about being able to meet one another. When I see what continues to happen in Canadian society around First Nations, I say we have a whole lot of reconciliation to do yet. Because things are still happening. It isn’t that it stopped happening with the residential schools closing. There are things still happening and we are seeing the effects — La Loche in Saskatchewan; now we’re talking about Attiwapiskat again. Canadians have to be concerned about this as a Canadian problem.”