The place where he felt at home — where he felt understood, welcomed and valued — was an ethnic Vietnamese parish. To this day, Nguyen considers Vietnamese Martyrs parish his home parish in Toronto. It was his launching pad into St. Augustine’s Seminary, the priesthood, canon law and his ministry as bishop.

The importance of ethnic parishes in the Catholic mosaic of Toronto has been highlighted by a sweeping new survey of Canadian social values released last week by the Angus Reid Institute and the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. The survey found big differences between immigrant and established Canadians in social attitudes toward sexual morality, assisted suicide and the advancement of women.

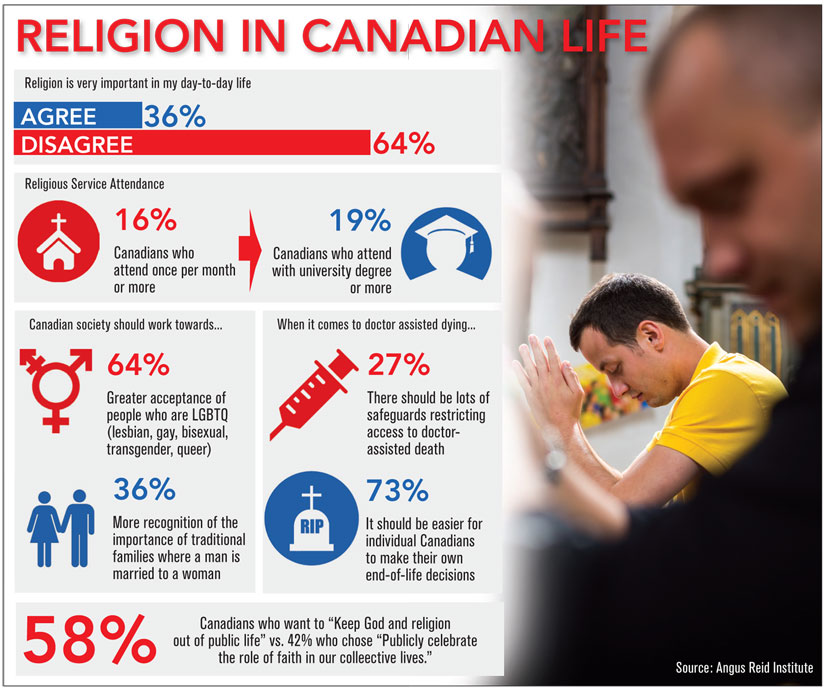

But the biggest immigrant/non-immigrant split is on the question of religion. Across Canada a clear majority told Angus Reid they thought Canada should “keep God and religion completely out of public life.” But for new Canadians, the majority of immigrants thought Canada should “publicly celebrate the role of faith in our collective lives.”

This fault-line is no surprise to anyone who has witnessed the vitality and commitment on display every Sunday in dozens of Toronto parishes where immigrants are the dominant force. The Archdiocese of Toronto celebrates Mass every Sunday in more than 30 languages. There are pastoral councils to co-ordinate service to Chinese, Polish, Hispanic, Portuguese, Italian, Vietnamese and Filipino Catholics. There are ethnic or national parishes for Tamil, Chinese, Korean, African, Brazilian, francophone and many other groups.

“When we talk about the multicultural, it enriches all of us,” said Nguyen. “It’s just a beautiful thing when we have so many different ethnic parishes in our diocese here, the liturgy being celebrated in so many languages in our diocese every Sunday. The life of the Church is vibrant and enriched with all these languages and cultures and experiences.”

Immigrant or not, there is “a sort of fault line between people who are religious and people who are not in Canadian society today,” Angus Reid research associate Ian Holliday told The Catholic Register. “That’s certainly something we see.”

Angus Reid researchers divided Canadians into five segments. This “segmentation analysis” found 20 per cent of us are “faith-based traditionalists.” That doesn’t mean that all these people are church-going and conservative. In fact, 15 per cent of this group claims no religious identity. But this segment of the Canadian population is at odds with the rest of the nation over assisted suicide, gay marriage and the role of religion in public life.

Three-quarters of faith-based traditionalists want safeguards and restrictions on assisted suicide versus only 27 per cent of the general population who want “lots of safeguards.” A third of faith-based traditionalists go to church or other religious services every week, versus just 11 per cent of the general population. Almost two-thirds of faith-based traditionalists want to emphasize “more recognition of the importance of traditional families” versus 64 per cent of Canadians who think “greater acceptance of people who are LGBTQ” should be our goal.

The faith-based traditionalist segment in the Angus Reid analysis is the most immigrant-heavy segment, with 26 per cent who either immigrated or are children of immigrants.

“New immigrants to Canada tend to be more religious and more interested in seeing that religion be a part of public life in society here,” said Holliday.

But that’s not really a change, said St. Jerome’s University sociologist David Seljak.

“Immigrants have always been the backbone of religious growth in Canada. It’s not a new thing,” Seljak said. “The role of immigrants has just become more stark. It’s always been there, but now we can see it in stark relief because the rest of the population has changed.”

As settled Canadians have drifted into a more secularized, skeptical mindset and stayed away from churches, synagogues and mosques, they’ve become more like other industrial and post-industrial Western societies — particularly in Western Europe. The faith-filled lives of Africans, Middle Easterners and Asians stand out in contrast, said Seljak.

The role of ethnic parishes in helping new Canadians settle in and find their feet remains a great strength of the Catholic Church in Canada, Seljak said.

“The immigrant Church acts as a kind of refugee and immigration integration centre,” he said. “These communities help people integrate into Canadian society.”

But it isn’t just about what the Church does for immigrants. It’s also what immigrants do for the Church.

“It’s also a question of enculturation,” said Seljak. “There isn’t just one form of Catholicism — a kind of Canadian form. You allow these other forms to exist.”

On church attendance, the Angus Reid numbers disprove the cliché about universities as religious deserts, where the secular spirit has crowded out and belittled any notion of religious devotion. In fact, Canadians with a university degree or better are those most likely to attend church weekly or more than once a week. Almost one in five university graduates (19 per cent) attend religious services at least once per month, compared to just 16 per cent of Canadians in general.

The numbers “speak against the kind of common mythology that universities are these secular monsters that will turn your devout children into atheists,” said Seljak, who is famous for teaching a University of Waterloo-St. Jerome’s course on Catholic social teaching known as “Evil 101.”

As other surveys have shown, the Angus Reid poll of nearly 4,000 Canadians confirms that the largest religious grouping in the nation is those who claim no religious identity. More than one-third (34 per cent) of Canadians have no religious affiliation. The second largest group is Catholics at 29 per cent.

Graphic by Lucy Barco

Graphic by Lucy Barco