National polls have continued to highlight the desire for more and better hospice and palliative care for the dying, yet only 16 to 30 per cent of terminally ill Canadians have appropriate access to such services, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

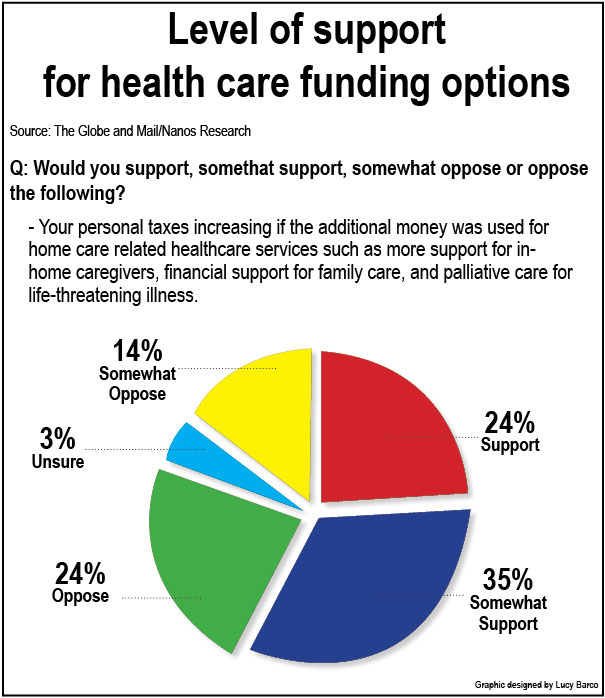

How strongly Canadians feel was revealed in a Nanos-Globe and Mail survey conducted at the end of October. Almost 60 per cent of Canadians said they would pay higher taxes if the public health system paid for in-home caregivers, financial support to families caring for loved ones and palliative care, according to the poll.

That backs up a Harris/Decima poll from 2013 when 96 per cent of Canadians said they support hospice and palliative care for the dying. In Parliament, a private member’s bill calling for a national strategy for palliative care has been gaining widespread support.

Catholic health providers are demanding a change. At the end of a Nov. 7-9 conference in Ottawa organized by the Covenant Health Palliative Association, Catholic health care institutions came away asking for changes to the Canada Health Act that would see home and palliative care covered by provincial health plans — just like X-rays, blood work and family doctor visits.

The Catholic institutions have popular opinion on their side. More than four out of five Canadians (85 per cent) told an Ipsos survey in August they wanted palliative care to be an insured service under the Canada Health Act.

Home care is currently not covered under the Act. What financial support there is varies by province, said Covenant Health’s Karen MacMillan, senior operating officer of acute services at the Grey Nuns Community Hospital in Edmonton.

“The Health Act was written in the ’60s. Really, what it covered was acute care services,” MacMillan said. “There are some who are worried that if you open up the act that it becomes a huge negotiation and it’s years in the making and it just bogs down, versus amending the act to include palliative home care.”

People would rather die at home, but Statistics Canada reports 70 per cent of deaths in Canada happen in hospitals.

“They’re dying in the most expensive setting,” said St. Elizabeth Health Care spokesperson Madonna Gallo. “It’s obviously not simple or straightforward or it would have happened already, but if we could shift some of those resources into other areas of the system and pro-actively provide more palliative care sooner, and in other types of environments like home and residential hospices — quality palliative care can save the system a lot of money over time.”

“They’re dying in the most expensive setting,” said St. Elizabeth Health Care spokesperson Madonna Gallo. “It’s obviously not simple or straightforward or it would have happened already, but if we could shift some of those resources into other areas of the system and pro-actively provide more palliative care sooner, and in other types of environments like home and residential hospices — quality palliative care can save the system a lot of money over time.”

Even if Canadians are willing to pay higher taxes to access palliative care at home, they might not have to, according to St. Elizabeth senior vice president Nancy Lefebre.

“People always talk about not having enough money in the health-care system. And the concern is, is that a reasonable goal? Will it bankrupt us?” said Lefebre.

“I think we need to be looking at the fact we already spend $220 billion in health care, of which home care is only five per cent. We have the money. It’s how we currently utilize the money.”

Just declaring home care services covered under the Canada Health Act doesn’t magically make non-existent services available, warns Catholic Health Association of Canada executive director Michael Shea.

“There are other factors in terms of the co-ordination and delivery of palliative care that need to be addressed and understood within the system as well,” Shea said.

“It’s going to cost us more money to set it up, but then if you set it up you (will) start to see the flow then happening into the community and you can actually take some resources out of the more costly system,” said MacMillan.

Today, the palliative care system relies heavily on the labour and the bank accounts of ordinary Canadians caring for their parents and other loved ones at home. Half a million Canadians are purchasing home care services. The Covenant Health Palliative Care Association estimates that families typically shoulder 25 per cent of the cost of palliative care at home.

With Canada expected to be home to 3.3 million seniors over the age of 80 by 2036, compared to just 1.3 million in 2009, demands on family are rising fast. St. Elizabeth Health Care research suggests 58 per of Canadians expect to become caregivers in the near future.

“It actually becomes a huge cost and burden to the family or to loved ones to try to keep someone at home, including drug costs and supplies — all kinds of things. It becomes very onerous,” said MacMillan.

In 2012, Statistics Canada reported almost half a million Canadians needed help with a chronic health condition but did not receive that help.