Since cameras were invented, they’ve been used to document the lives of poor people and the injustice of their conditions. That tradition lives on in Toronto, in the photographs of Vincenzo Pietropaolo.

“He is a very fine photographer who has made a significant contribution to documentary photography in Canada,” Ann Thomas, senior curator at the Canadian Photography Institute, told The Catholic Register via email. “Vince’s work has and always will enjoy a critical place in the tradition of Canadian documentary photography.”

The role of photography in social justice has a long history. In the 1880s, Dutch immigrant Jacob Riis used a camera to expose appalling conditions the poor faced on Manhattan’s lower east side for his book How the Other Half Lives. Just before the First World War Canadian photographer Arthur Goss documented similar conditions in Toronto’s Irish slums. In the 1950s, Canadian photographer Richard Harrington documented famine and the devastation of Inuit culture. In 1992, Andrew Stawicki launched his PhotoSensitive collective of crusading photographers by documenting the homeless and the poor for Toronto’s Daily Bread Food Bank.

When 18-year-old Pietropaolo began photographing his Italian immigrant neighbourhood of Toronto in the 1960s, he didn’t know he was stepping into a long tradition of photojournalism on behalf of the poor. The poor were just his neighbours and friends and he was learning photography.

By the time he was 40, Pietropaolo knew what he was doing when he walked away from a successful career as a city planner in Toronto. As a freelance photographer, he sought work with unions and social justice organizations, documenting the immigrant and working class experience.

“Photography was always in my heart and I was photographing all along,” he said. “Then I thought I should either stop thinking about photography and concentrate more on my planning career or, you know, one or the other. So I gave up my job.”

He put years of work into his 2009 book, Harvest Pilgrims, documenting the lives of migrant labourers who work on Ontario farms. His 2006 book, Not Paved With Gold, shows us the lives of Italian immigrants in the 1970s. Celebration of Resistance brings together three years worth of protest photographs from the early years of Premier Mike Harris’ “Common Sense Revolution” in Ontario. Invisible No More presents the ordinary lives of people with Down’s syndrome, autism and other disabilities.

“You know there’s the tortoise and the hare story? He’s the tortoise,” Loyalist College photojournalism program co-ordinator Frank O’Connor said of Pietropaolo. “We live in a world of sexy, image-moment, entertainment, pizzaz — all that sort of stuff. But documentary photography isn’t necessarily like that… The strength of his work is that he has documented not the moments but the existence of people.”

Almost all of Pietropaolo’s projects have stretched over years, gradually maturing until he can present an entire history.

“In looking back on my work, I realize that much of my work has a religious connotation to it,” said Pietropaolo. “My migrant workers, I called them Harvest Pilgrims. They’re like pilgrims who come every year for harvest. Pilgrimage, of course, is associated with religion. But in this case, these guys are pilgrims to their workplace.”

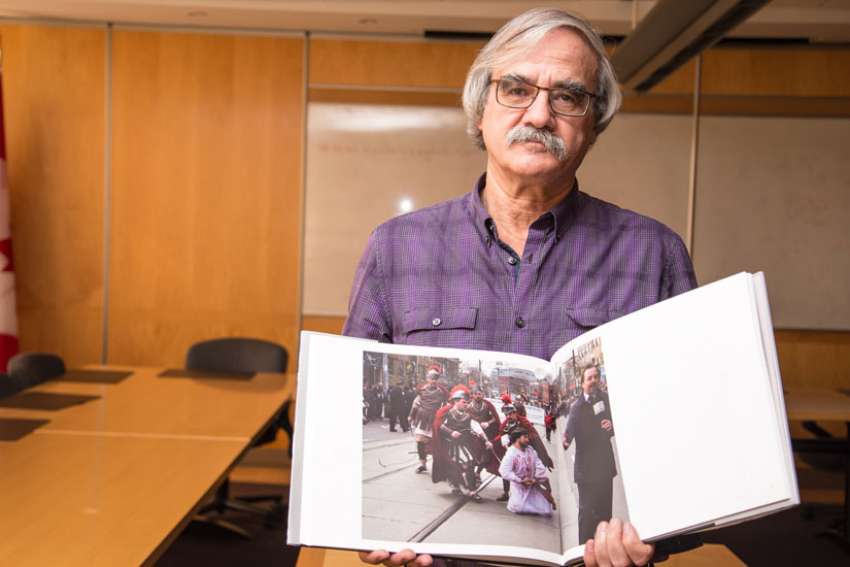

The other theme that comes up over and over again is migration, displacement and life in exile. His latest book, Ritual, presents a 50-year history of the Good Friday procession through Toronto’s Little Italy neighbourhood.

“I started photographing this as part of an immigrant identity,” Pietropaolo said. “Before you can integrate anyone you have to accept their immigrant identity…. The Church is oftentimes the most visible part of your immigrant identity.”

As a boy born in Italy, who grew up in Toronto, whose parents were working class, Pietropaolo doesn’t document immigrant experience from the outside.

“Being an immigrant marked me. My experience in Canada is from the point of view of an immigrant,” he said. “That marked my life as a photographer. I started photographing the immigrant experience — not just the Italian immigrant experience but other groups.”

A project for the Royal Ontario Museum featured refugee families, another one offered a comprehensive history of the waves of immigration that washed through the Kensington Market neighbourhood of Toronto.

The immigrant experience led him to other subjects.

“I became interested in photographing the working class — working class cultures. That led me to the labour movement,” he said. “I was interested in portraying and giving a voice — maybe that’s too lofty sounding — but certainly documenting people who I felt were vulnerable, who were suffering social injustices.”

Pietropaolo’s concentration on social justice kept him close to the Church. The Harvest Pilgrims project was financed by the United Food and Commercial Workers, who have argued that migrant agricultural workers should have the right to join a union, but also by the Sisters of St. Joseph and the Sisters of Providence, who believe the Church is called to minister to anyone who is poor, alone and human. When Pietropaolo went looking for places where migrant workers gather, he found them in churches.

The same is true of his work documenting the lives of permanent immigrants.

“Historically, churches have always been at the forefront of helping immigrants with all sorts of programming. I can speak from experience with the Italian Church in Toronto. It was the Italian parish of St. Agnes in the 1930s, historically acting as the major community centre, helping immigrants find jobs, helping them with bureaucratic problems they might have had, finding rents. Long before soup kitchens became fashionable, churches were already doing that,” he said.

Pietropaolo’s own history in photography spans several waves of technology. When he started he rolled his own Ilford 400 black and white film and spent his evenings in the darkroom. He has shot colour negatives, colour slides and works today with digital cameras and Photoshop. But the photographer isn’t pumping out artifacts of his camera or computer. Pietropaolo’s job is to tell a story.

Film develops in a darkroom in a few minutes. A story develops through a lifetime.

“What a great testament,” said O’Connor. “To say you can apply your passion in your life and at the end of the day, when you’ve breathed your last, you’ve created a body of work that lasts.”

(To learn more about Vincenzo Pietropaolo's photography, visit vincepietropaolo.com)