“We get involved when there’s a problem. We’re responding to a problem — we’re not creating a problem,” said Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Hamilton executive director Rocco Gizzarelli.

But it doesn’t always work.

“It shocks me that a child can go through a system and there’s no one that stops to look down at that kid and say, ‘Hey, wait a minute. What do you need? What are you feeling? What would you like to do?’ I think that needs to change,” Child and Youth Services Minister Michael Couteau told The Catholic Register. “Because that does happen.”

Couteau is driving the biggest legislative changes in Ontario’s child welfare system since the Child and Family Services Act was first passed in 1990 — a 250-page reform bill that has already been through first reading and will be studied in committee this month. If it passes this spring, by next year the new law will protect older teens up to the age of 18 (from the current 16), will require greater transparency and accountability from children’s aid societies and will mandate that every decision made about a child in the system be driven by the child’s best interest. It’s a change driven by ever-growing evidence of an inadequate system stained by several cases of child deaths.

But it’s a law and you can’t legislate love. It takes something more than an agency to raise a child, and there are problems that no single piece of legislation can solve.

The system is complex, with 47 independent children’s aid societies, each with its own history, board of directors and suite of services. There’s fear in many agencies that the province’s next move might be massive centralization and control from Queen’s Park.

“We’ll give the minister tools, to have a bigger stick, to force the children’s aid (societies) to do what we want them to do,” said Ontario Child Advocate Irwin Elman, explaining the logic behind the reform bill. “So that’s why in the bill there’s this idea that the minister can appoint members of the board of every children’s aid. Is he going to do that? He has the power.”

It’s not just appointing board members. The new act will allow the Minister of Child and Youth Services to take over boards, to amalgamate societies, to issue compliance orders in particular cases. The reform also opens up the possibility of creating a single, centralized, provincial adoption agency.

Could that mean the few religiously based children’s aid societies (two Catholic societies in Toronto and Hamilton, plus Jewish Child and Family Service of Greater Toronto) are in trouble?

“I do worry about that,” Hamilton’s Bishop Doug Crosby said. “At the same time I have hopes that we will be engaged in the dialogue.”

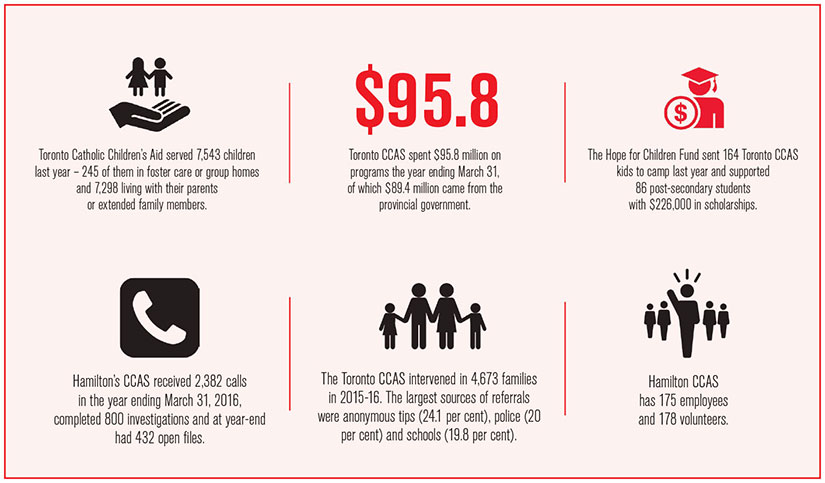

(Graphic by Lucy Barco)

(Graphic by Lucy Barco)

“There’s a critical role of faith in all this that they want to eliminate. You see in the legislation, amalgamation is in there,” said Gizzarelli.

At the beginning of February, Couteau’s office told The Catholic Register it was trying to find a date for a face-to-face between Crosby and Coteau.

Coteau knows about the fears, but is convinced that the 47 children’s aid societies and his ministry are all pulling in the same direction.

“I think there’s a buy-in from the system. I don’t think I have met one person in the system who doesn’t acknowledge that this piece of legislation is overdue and it’s going to make major changes,” he said.

“We’re obviously watching and talking about it,” said Catholic Charities executive director Michael Fullan, a member of the board at Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Toronto. “The ministry has taken over children’s aids in the past — going back 10, 15 years ago. It’s happened. It’s rare. They have forced amalgamations already in the province. This is not new.”

If everybody’s nervous, Couteau understands.

“It’s going to be uncomfortable for some folks,” he said. “When you start talking about appointments, the minister having the right to appoint, to take over a board, having the ability to just force people into mergers — it makes people uncomfortable.”

But Coteau insists those measures are “just a small piece of the legislation.”

“When we’re talking about children, we should have challenging conversations that do make us uncomfortable, that make us think differently and allow us to put in place what we feel is necessary to protect children,” he said.

Amalgamating Catholic and Jewish agencies out of existence isn’t on Coteau’s to-do list.

“I’ve been on the record many times saying that I believe there is value in having a Catholic system, there’s value in having a Jewish system,” Coteau told The Catholic Register. “Especially considering that in the (new) legislation you will notice there’s a centrepiece around indigenous and black youth and building culturally relevant programs or initiatives within the larger systems…. We can learn from what the experiences have been like in the Jewish and Catholic boards, because they’ve been doing this for years. I think there’s actually benefits to us adopting processes, ideas and thoughts from other systems outside of the general, public system itself.”

When it comes to the make-up of society boards, Couteau’s worry is that they don’t necessarily reflect the people they serve. There’s an awful lot of black families involved in the system and not very many black people on children’s aid society boards.

The societies have not collected race-based data in the past and the new legislation will require it. But one look at the group home and foster care population in Toronto found 41 per cent of the kids were black.

“I don’t want to get into the business of just picking random names and appointing people to a board,” Couteau said. “But what I think is necessary is, for example, making sure that that board is reflective of the clients it takes in — to make sure that that board has the voices of cultures, like indigenous voices.”

“In terms of diversity, we’re working on that,” said Toronto Catholic Children’s Aid executive director Janice Robinson. “It is a requirement for all board members to be Catholic.”

Robinson’s preference would be to see children’s aid societies solve board diversity problems on their own. Once board members start getting appointed at Queen’s Park it could threaten the “Ontario model,” which holds up community boards as the best way to ensure the societies are responsive to their local community.

Reforms to the Child and Family Services Act are “overdue,” says Ontario’s Child and Youth Services Minister Michael Couteau. Among other changes, his reform bill will mean protection for children to the age of 18 instead of the current 16 years of age. (Photo by Michael Swan)

Reforms to the Child and Family Services Act are “overdue,” says Ontario’s Child and Youth Services Minister Michael Couteau. Among other changes, his reform bill will mean protection for children to the age of 18 instead of the current 16 years of age. (Photo by Michael Swan)

“The relations CASs have with their communities is very much treasured. It varies across Ontario,” she said.

In the academic literature, involvement in child welfare is associated with homeless, long-term poverty, unemployment and education deficits. Domestic violence is a huge issue throughout the system and it gets passed from generation to generation.

“The generational nature of child welfare services is something we want to disrupt. We want to stop it,” said Robinson.

There’s no magic formula for getting different outcomes, especially when it comes to lifelong poverty, said Gizzarelli.

“The (academic) literature and the child advocate have gone on record saying we produce poor outcomes for kids. But people need to put in context that a lot of these kids come to us already troubled,” said Gizzarelli. “There seems to be this focus on the poor outcomes. There’s poor outcomes when there is no system either.”

In the chicken-or-egg debate over whether poverty creates the need for children’s aid or children’s aid sets up kids for a life of poverty, there are still unanswered questions, Robinson said.

“We are really just beginning to understand that there are social determinants, predictors if you will, of the need for child welfare services,” Robinson said. “The legislation doesn’t tell us the social determinants of how people come to our door. It’s poverty. It’s homelessness. It’s vulnerability for all kinds of other reasons.”

Couteau says his child welfare reform plans are part of his government’s overarching poverty reduction strategy, which includes a 10-year commitment to end chronic homelessness, increases in minimum wage, access to dental care for 45,000 low-income kids and now free university and college tuition for about 150,000 students whose families make less than $50,000 per year.

While children’s aid societies have a long history of dealing with the effects of poverty, it is not a problem they were ever set up to solve on their own, said Hamilton’s Gizzarelli.

“Poverty is a social issue,” he said. “It’s not just a child welfare issue. It’s a community issue. We have a collective responsibility…. To isolate it just to child welfare, we’re not looking at the problem.”

There are no magic bullets, no sure-fire formulas. Kids are born into poverty, family dysfunction, social isolation, racism and exclusion, patterns of violence, poor housing, no housing, addiction and 100 other things they can’t control. From the Catholic point of view, faith is how people stand up against those odds.

For Robinson, faith is not some abstract philosophy but a practical tool.

“It’s not an old-fashioned idea at all. It’s a very integral part of what makes a person,” Robinson said.

The families who come to Catholic Children’s Aid have declared they want Catholic services.

“One of the things I find in the families we work with is that loneliness, social and emotional loneliness, is a big factor,” Robinson said. “Connection to the Church can be a big assist.”

Cultural and religious identity, the practices of prayer and discernment, build “resilience” in all children, not just kids in care, she said.

“In this day and age, we need an anchoring point for kids,” said Gizzarelli. “We do know that bringing faith into people’s lives produces different kinds of outcomes.”