It has also stopped holding information sessions for parishes and other groups interested in sponsoring refugees because of the lack of spots available for refugees.

“People are very frustrated,” ORAT director Martin Mark told The Catholic Register in an email. “We are very disappointed. This is not a good situation.”

The Archdiocese of Toronto is one of the largest sponsorship agreement holders in Canada. Sponsorship agreement holders, or SAHs, hold a formal relationship with the Ministry of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship which gives them special access to Canada’s private refugee sponsorship system. In April all 100 sponsorship agreement holders were given their annual quota for 2017, setting the number of applications they would be allowed to submit to the government’s Winnipeg processing centre for refugee applications.

Toronto’s limit was set at 375, a number ORAT had reached in the first three months of 2017. The Catholic refugee sponsorship agency has another 100 cases pending that it will not be able to submit to the government until 2018.

Toronto’s problems are shared across the country. The refugee office in the Diocese of London received a 2017 quota of 157, but has 401 applications in process. London will have to decide which 244 applications can wait until 2018.

“The caps, which have been in place for a number of years, have certainly been a problem,” said the Mennonite Central Committee of Canada national migration and resettlement program co-ordinator Brian Dyck.

Dyck sits on the Sponsorship Agreement Holders Association council, which works with the government on the private sponsorship system.

“All of us have people coming to us on a regular basis who want us to help them and it’s difficult to say over and over that we cannot help,” Dyck wrote in an email to The Catholic Register. “No one likes that. These limits have certainly built up a shadow backlog of cases that are not on any government database but are in our minds and hearts. It is difficult to know how to unburden our hearts of this backlog.”

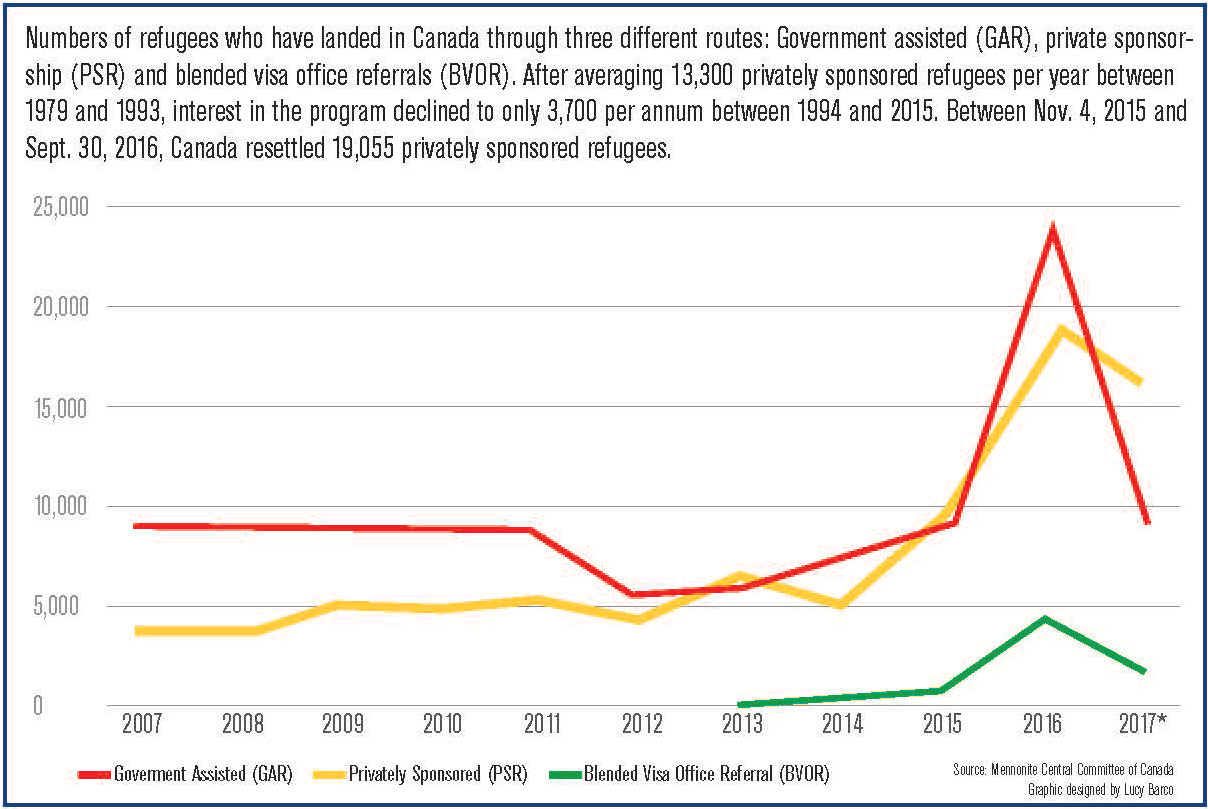

Source: Mennonite Central Committee of Canada. Graphic designed by Lucy Barco

Source: Mennonite Central Committee of Canada. Graphic designed by Lucy Barco

The official backlog stands at about 45,000 refugees with sponsors waiting for them in Canada. Last year Canada resettled 46,700 refugees. Syrians have been a large proportion of that number. Between Nov. 15, 2015 and Jan. 29, 2017, 40,081 Syrians landed in Canada, including 14,274 who were privately sponsored, mainly by faith communities. Ottawa has set a target of 16,000 privately sponsored refugees in 2017 out of a total of 40,000 protected persons and refugees it plans on welcoming to Canada this year.

“More refugees have landed in Canada last year and this year (if they meet their target) than any time in at least the last 15 or so years,” said Dyck.

But that doesn’t mean that increased landings are keeping up with the number of new applications.

“The applications that have gone into the system have consistently been much higher than the number of applications that have been finalized. … The number of applications in the system is huge and growing,” Dyck said.

By increasing the number of refugees actually landing in Canada and keeping a tight lid on the number of new applications, Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen plans to bring the applications and landings back into balance and cut the time between an application submitted and a refugee arriving down below 12 months in 2019.

“It will not be an easy goal to meet,” said Dyck. “It comes down to a math problem. We need to finalize more cases than the number that come into the system. In that ledger, I think SAHs are in agreement that they want to see more landings and fewer caps, and that is what we push for.”

How long a refugee waits for a plane ticket to Canada varies greatly depending on where the refugee is. The current average processing times for refugees in Ethiopia is 74 months (six years and two months), in Pakistan 73 months, in Ghana it’s 54 months, in the Philippines 54 months, in Saudi Arabia 13 months, in Lebanon 12 months.

Dyck sees no evidence that the intense interest in Syrian refugees has resulted in longer delays for non-Syrians.

“Other major refugee populations stayed reasonably stable in terms of landings or even increased,” he said.

With 64 million refugees and displaced persons around the world, resettling small numbers in Canada saves lives, but it doesn’t solve the larger problem, said Dyck.

“I pray for an end to conflicts that are compelling people to flee their homes,” he said. “Because that is ultimately the only solution to the world’s huge and growing refugee crisis.”