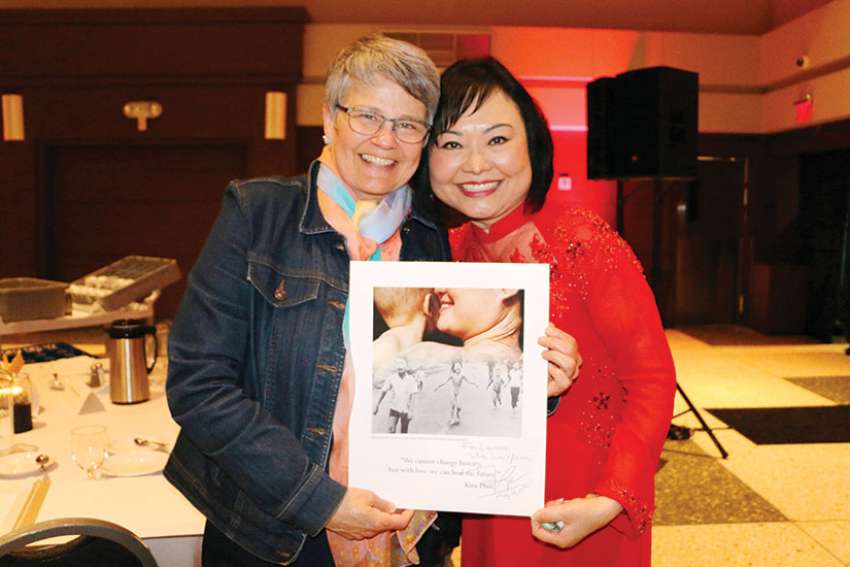

That haunting image, snapped by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut, received a Pulitzer Prize and illustrated the terror of that war for the rest of the world. The girl in that photo survived, and is now a Canadian citizen, grandmother and ambassador for peace.

Kim Phuc was the special guest last month at the 19th annual Focus on Life Gala, a fundraiser for pro-life efforts in Vancouver. “At nine years old, I knew nothing of pain,” she said.

That is, until South Vietnamese planes dropped a napalm bomb on her hometown of Trang Bang on June 8, 1972, mistaking civilians for enemy soldiers. The napalm badly burned Phuc’s body and the attack killed two of her cousins as well as two other villagers.

“Napalm is the most terrible burn you can imagine,” she said.

One journalist later described the scene, saying another child had been so badly burned in the attack that “it looked like it was clothing hanging off his body, but it was his skin.”

Photographers and local soldiers rushed Phuc and other children to the hospital.

“Unfortunately, the soldiers who tried to help me on the road didn’t realize when they poured water on me, they made the napalm burn even deeper. I lost consciousness,” she said.

“When my parents found me three days later, I was in a hospital morgue. The doctors had done everything they could and I had been left to die.”

Phuc said it was a “miracle” when she was transferred to a burn clinic in Saigon for special treatment. She spent 14 months in hospital and had a total of 17 operations.

“The pain was unbelievable. I almost died many times,” she said. “Facing pain at an early age was harder than any challenge that should happen to a child.”

Her final operation was in 1984 in Germany. It gave Phuc the freedom to finally move her neck. She said one of her arms and her back were badly scarred and her skin was tight and itchy.

She completed laser skin treatments in Miami, Fla. earlier this year to heal the scars.

“My dream was to become a doctor,” she said. “Do you know why? Because I stayed in the hospital too long!”

Phuc was thrilled when she was accepted into medical school in Saigon. Unfortunately, she was about to be re-victimized.

“The Vietnamese government found me and decided to use me as a war symbol for the state. Officers took me out of school for propaganda interviews. I said no. They didn’t care,” she said.

“I became a victim a second time. I was not a political person; I wanted peace.”

After a few years, she met the prime minister and begged him to let her finish her studies. He arranged for her to go to Cuba in 1986, where she met her fiancé.

Before leaving for Cuba, Phuc had discovered a faith that helped her cope with the acute suffering she’d experienced since she was nine years old.

“Like most Vietnamese children, I was raised in the Cao Dai faith. But something was missing. I kept looking for answers. In 1982, I found them in the Bible. I became a Christian.”

Her new-found faith taught her about forgiveness.

“I was holding a lot of anger and hatred for those who dropped the bombs and those who were controlling me. I knew I didn’t want to live my life like that,” she said.

“With God’s help, I learned how to transform that bitterness into forgiveness and how to forgive my enemies. It wasn’t easy, but I did it.”

Phuc married Bui Huy Toan in 1992 and they were given permission to honeymoon in Moscow. When Phuc learned the flight would stop in Gander, Nfld., to refuel, she planned their escape.

The newlyweds got off the plane in Gander and sought political asylum. Later, Phuc became a Canadian citizen, gained honorary doctorates from six universities and launched Kim Foundation International, a non-profit dedicated to helping child victims of war and violence. She also met a man who said he was partly to blame for the napalm attack, and personally forgave him.

“If that photograph was determined to follow me, I wanted to live a life of purpose with it, to find a way to help other children who had suffered,” said Phuc, who eventually settled in Ajax, Ont., raising two sons with her husband.

Her foundation helps build schools, hospitals and orphanages as well as providing medicine and wheelchairs to children in countries such as India, Uganda and Tajikistan.

She praised the Archdiocese of Vancouver, the Christian Advocacy Society of Greater Vancouver and Signal Hill, the partners behind the Focus on Life initiative, for their efforts in their communities.

“By encouraging young people to value themselves and to love and respect life and one another, you are helping to create a better world, a more joyful world.”

The fundraiser was held to support the Value Project, training for teens to value themselves and each other through retreats and school activities, as well as future media efforts with medically accurate information about pregnancy and contact information for nearby crisis pregnancy centres.

Archbishop J. Michael Miller said Phuc’s story is a powerful example of forgiveness and transformation.

“We all have a mission to treasure, care for and support the gift of human life,” he said.

“All of us here, regardless of the religious and spiritual tradition we follow, must continue to come together to build a society in which the dignity of each person is recognized and protected, and the lives of all are defended and enhanced.”

(The B.C. Catholic)