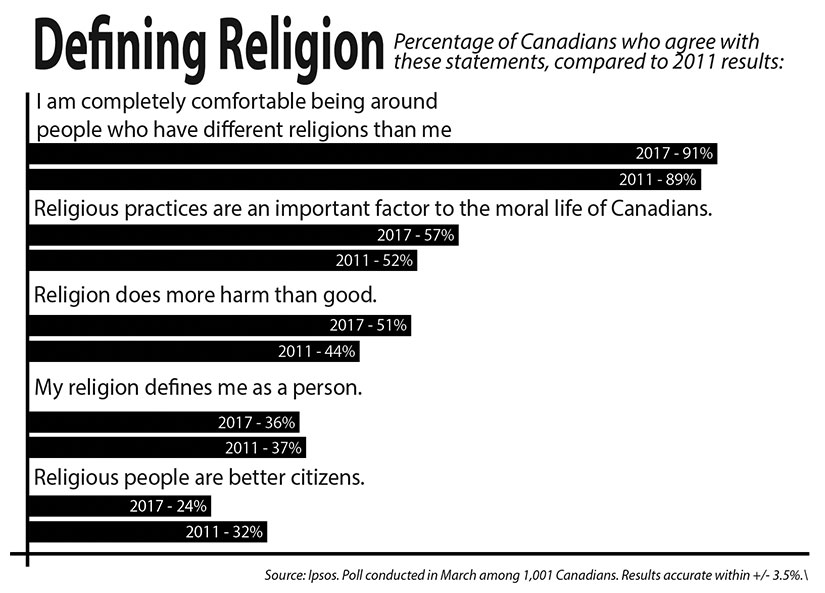

Ipsos Public Affairs surveyed 1,001 Canadians online from March 20 to 23 and the results suggest more Canadians are moving away from formal religions.

About 51 per cent of Canadians polled by Ipsos Public Affairs agreed that “religion does more harm in the world than good.” That’s a seven-point increase from a similar questionnaire that was conducted in 2011.

“A couple of points of shift is not a big deal because that’s all in margin of error, but when we have changes of seven points in six years ... that’s a significant shift,” said Sean Simpson, vice-president of Ipsos Public Affairs.

Simpson told The Catholic Register that in a technological age where information is so easily accessed, Canadians have a “higher sensitivity” to news of religious radicals committing acts of violence and terrorism.

He also attributed this shift in public perception to the growing secularization of Western culture.

“If you go further along in the study, only 22 per cent feel that it’s important to their political thinking,” said Simpson. “And it’s only 29 per cent among Catholics, which means that seven in 10 Catholics say it’s not important to their political thinking. They are likely not supporting political parties based on those traditional values.”

However, Reginald Bibby, a sociologist at the University of Lethbridge who studies religion trends with the Angus Reid Institute, says Canadians are much more complex that the survey reveals.

“By our standards, in terms of sociology of religion, all I’m saying is Ipsos has very loose items,” he said. “That item about religion doing more harm than good ... our figure was 51 per cent positive on that, so virtually the same figure.”

Bibby explains that 51 per cent in either direction should be largely understood as a 50/50 split and Canadians have been split on this particular statement for many years.

Bibby’s data comes fromresearch for a book he published in April called Resilient Gods.

In his research of data dating back to 1975, he found that a “solid core” of 30 per cent view religion as a central part of their lives. Another 30 per cent reject religion, while the remaining 40 per cent are somewhere in the middle.

Bibby said that depending on any number of social and cultural factors, these groups would shift slightly over the years. However, he believes religion is here to stay. With a steady increase in immigration, Bibby said the “pro-religious core” in Canada is assured for the foreseeable future.

“Frankly, we’ve been asking these same questions for years,” said Bibby. “It’s one of the frustrating things as an academic when you’re doing research on stuff like this, you have to meet all kinds of standards, and it’s slow and there’s a review board. .. but then you come along and see a few poll items and the media jump all over it like it’s some big finding.”

Bibby said that comparing data from 2011 to 2017 is much too short a time frame to fully understand the direction in which Canadian perception on religion is going.

“If you had asked that question in 2001, you know what you’d be expecting, especially after 9/11,” said Bibby. “Had they done the survey in 2001, now that would be noteworthy.

Graphic by Erik Canaria

Graphic by Erik Canaria