For the first time in Canada’s 150 years, the biggest single category of households is people living by themselves. For the Church, this 21st-century reality is raising new pastoral challenges.

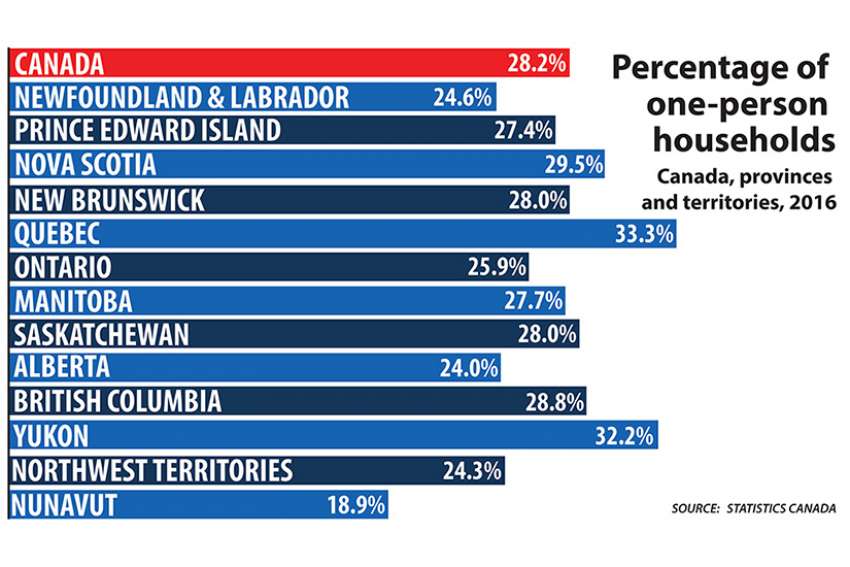

Households consisting of mom, dad and the kids are no longer the norm, according to the 2016 census. One-person households comprised 28.2 per cent of Canada’s 14.1 million private households last year. That compares to 26.5 per cent of all households that had couples with children.

It isn’t just Canada. Around the world advanced nations report that more and more people live alone. In France, 33.8 per cent of households contained just one person. In Japan, 34.5 per cent live alone. In Norway 40 per cent, Germany 41.4 per cent.

In Canada, a bare majority of 51.1 per cent of all couples live with their children — the lowest share ever.

But living alone doesn’t necessarily mean people are lonely, said Nora Spinks, CEO of the Vanier Institute of the Family.

“They may be living alone in a single-person household but may be very actively engaged in their community or very much connected,” Spinks told The Catholic Register. “You have to layer on top of that the technology we now have access to, the public transportation we now have access to. We can’t jump to the conclusion that because 28 per cent of households are one-person households that they are necessarily alone.”

Although many people have the social skills and networks to be content while living alone, loneliness is a rising pastoral issue in parishes, said St. Francis Xavier pastor Msgr. Edgardo Pan.

“You find it in many parishes,” he said. “It’s really a challenge.”

Pan recently received a letter from a parishioner who wanted to start up an outreach to the lonely of St. Francis Xavier’s Mississauga neighbourhood.

“The name of the group would be ‘Someone Cares.’ It’s for people who really feel neglected,” said Pan.

Pan’s parish has already run programs for newcomers, gathering individuals who have come to Canada to work. These parishioners remain in touch with their families mainly by Skype and telephone. The parish also hosts regular outreach to seniors. But the unmet need is ever present, Pan said.

Fr. John-Mark Missio, a pastoral and liturgical theology expert at St. Augustine’s Seminary, believes the epidemic of loneliness is much broader than the numbers suggest.

“We live in a time in human history when more people live alone than ever have in human history,” he said. “That’s striking. It’s disturbing. It’s really thought provoking.”

The census numbers only confirm a reality most Canadians already have sensed, he said.

“This isn’t just a theoretical reality. It’s what we actually live now. The Church does offer the best solution because the Church is a community, a body of believers,” said Missio.

For St. Patrick’s Brampton pastor Fr. Vito Marziliano, the numbers are a reminder that the parish has to remain open, welcoming and available.

“If we are welcoming — I think that’s the key word, hospitality,” he said. “I think the focus is to keep finding opportunities and be welcoming when, for whatever reason, they knock on your door.”

People living alone may be the most common type of household, but the fastest growing category is homes comprising at least three generations of one family. The overall percentage is small — just 2.9 per cent of households — but it represents 403,810 households nationwide. That’s an increase of 37.5 per cent since 2011 and means 6.3 per cent of Canadians live in a home where grandparents, parents and grandchildren share the same bathrooms and kitchens.

Multigenerational living arrangements are most commonly found among immigrant and aboriginal Canadians.

“There’s no question in some cultures that the grandparents are going to live with their children,” said Spinks. “For some, it’s a pooling of resources.”

It isn’t just a tight budget that pushes some families into the multigenerational model. The resources and workload to be shared can include child care, elder care, even running a family business.

“In some cases it’s a very positive experience. In others, it can be extremely stressful,” said Spinks.

Pan often spends time with older parishioners stressed out by life with Canadian-born grandchildren.

“The difference in culture — in conservative countries you don’t hear young people shouting at the elderly. Here they do that,” Pan said.

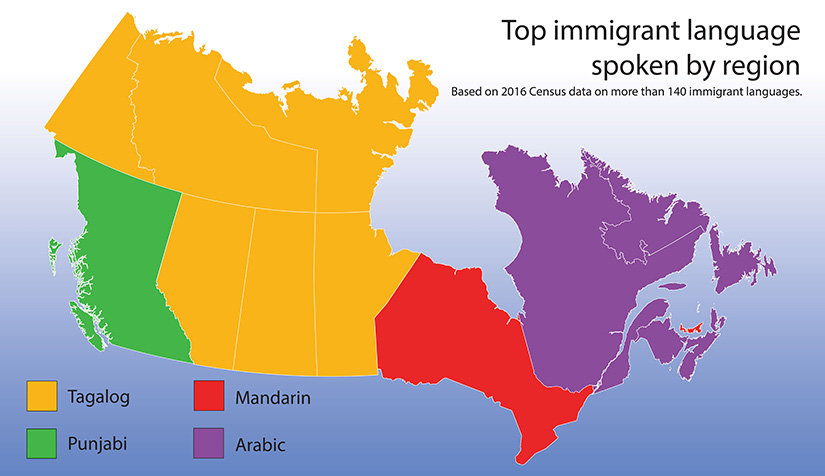

As immigration continues at record levels, language remains a pastoral reality — particularly in Canada’s big cities. More than 13 per cent of us (7.75 million people) claim a mother tongue other than English, French and the Aboriginal languages. More than three quarters of those people live in six metropolitan centres — Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, the national capital region, Calgary and Edmonton.

Among the fastest growing languages is Tagalog — the Filipino language heard in parishes from coast to coast. Ranked number seven in 2011, Tagalog is now the number four immigrant language, with more than half-a-million native speakers.

Among immigrant languages historically associated with Catholic parishes, Dutch, Ukrainian, Italian, German and Polish are all in decline. Across Canada, Italian speakers declined by 30,260 — a 6.9-per-cent drop.

The Canadian Church’s strategies for welcoming immigrants and accommodating their languages have evolved, said Marziliano.

“It’s far more than just language,” said Marziliano, who has pastored both Italian and multi-ethnic parishes. “It also has to do with culture. Even someone who may have surpassed their difficulty with language still worships in their culture.”

The face of the Church and the face of the nation is becoming more Asian. It’s not just the Filipinos on the rise. The number one non-official language in the country is now Mandarin, which leapfrogged from number nine in 2011. Number two is Cantonese. The two main Chinese languages are spoken by 1,204,865 people.

A census is just numbers. The pastoral reality of any parish is always more than that, because God calls us by name, not by number.

“What I see is a kind of wonderful United Nations that’s emerging in all of our parishes,” said Missio. “I think we’re actually reflecting that reality already.”

“I don’t think we’re going to hell in a handbasket and I don’t think we’ve achieved nirvana,” said Spinks. “I think what (the 2016 census) does reflect is how families adapt and how families adjust. They are the first to respond to changes in society and economy and environment.

“If we pay attention to those changes and understand those changes then we will all benefit. If we try to fight against it… we may risk less positive outcomes.”