“There’s many levels of poverty; it’s not just a monetary poverty,” said Teresa Kellendonk, who presented her paper on Feb. 1 to a meeting of the International Prison Chaplains Association held at the United Nations headquarters in New York.

Kellendonk is a vice-president of IPCA, which represents Christian prison chaplains around the world. She served as a prison chaplain herself for six years, and during that time she heard inmates say that they felt like animals or like bad people.

“Trying to get somebody to see the goodness of who they are because they’re born, because of their humanity… If we don’t enable them to see that, that’s spiritual poverty,” Kellendonk said.

Kellendonk was invited to present her paper to the conference.

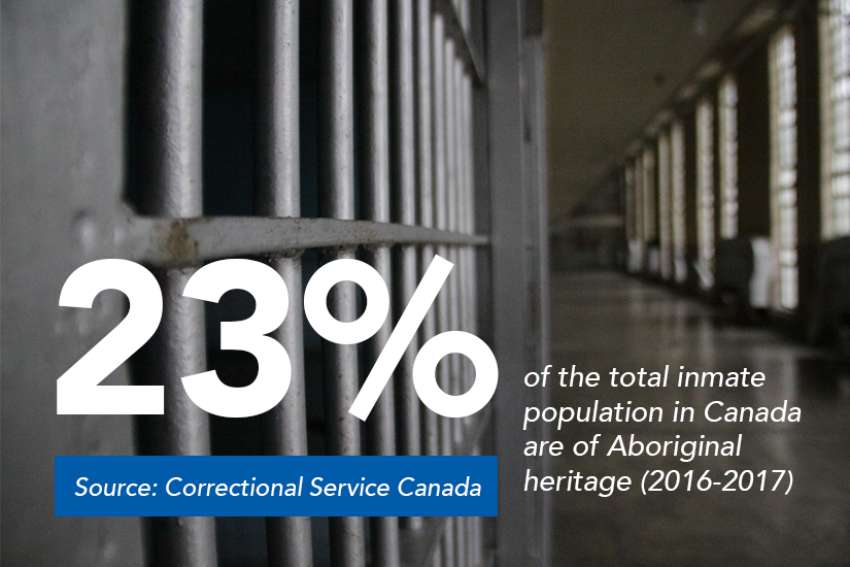

In her paper — entitled A Human Dignity and Faith Perspective on the Eradication of Poverty as One of the Main Root Causes of Incarceration — Kellendonk addresses the effect poverty has had on the Aboriginal community. In 2016-17 alone, inmates with Aboriginal heritage represented 23 per cent of the total inmate population, despite only representing three per cent of the total Canadian population, according to Correctional Service Canada.

“There’s a lot of poverty on our reserves… the legacy of residential schools, and there’s the generational poverty. When you have all of that, there’s an economic poverty, then there’s a political poverty,” Kellendonk said.

Aboriginal children alone are more than twice as likely to live in poverty than non-Aboriginal children, according to a 2016 study by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. The study says 51 per cent of First Nations children live in poverty, rising to 60 per cent for children living on reserves.

Child poverty rates also worsened between 2005 and 2010. The study calculated poverty rates on reserves and in the territories, something that had not been examined before.

“We have a generational poverty happening, and it’s a vicious cycle,” said Gary Gagnon, co-ordinator of the Office of Indigenous Relations for the Archdiocese of Edmonton.

In prison, chaplains serve an essential need for offenders, who often suffer from isolation from their community and their culture, said Kellendonk. This is especially true for Aboriginal offenders, she added.

Since 1992, Correctional Service Canada has had elders minister to offenders with sweat lodges and other spiritual practices.

“Elders are invaluable,” said Gagnon, adding they have traditional teachings that aren’t codified. “They’re living stories.”

Elders help inmates reintegrate back into society, according to the Correctional Service of Canada.

“Elders recognized that Indigenous inmates required healing to better understand their history, their challenges, and to develop a strong sense of identity so that they can move forward in their lives as productive members of society,” said Sara Parkes, a spokesperson for the CSC.