Immigrants are increasingly the driver for charitable giving in Canada, especially for religious charities, according to a new study by the Angus Reid Institute on behalf of the CHIMP Charitable Impact Foundation.

A close look at charitable giving by people born outside of Canada finds immigrants more likely to give than the general population and more motivated by faith. The Angus Reid study concentrated particularly on Chinese, Filipino and Indian immigrants, three leading sources of immigration to Canada.

“There are a number of stress factors that are really pressuring charities in general,” Angus Reid executive director Sachi Kurl told The Catholic Register. “You’ve got what I would suggest is a slackening of the giving muscle.”

Only seven per cent of immigrants born outside of Canada are non-donors, compared to 14 per cent of the general population. More than a third (36 per cent) of immigrants are classed as “Super Donors” who support multiple charities and spend over $250 per year — well ahead of just one-fifth (21 per cent) of the general population.

Over and over, Angus Reid researchers found that this spirit of generosity among Filipino, Indian and Chinese immigrants is driven by religious faith. Just over 70 per cent of immigrants told pollsters their personal faith has a strong influence on their views of charitable giving, compared to only 46 per cent of the general population who make this claim.

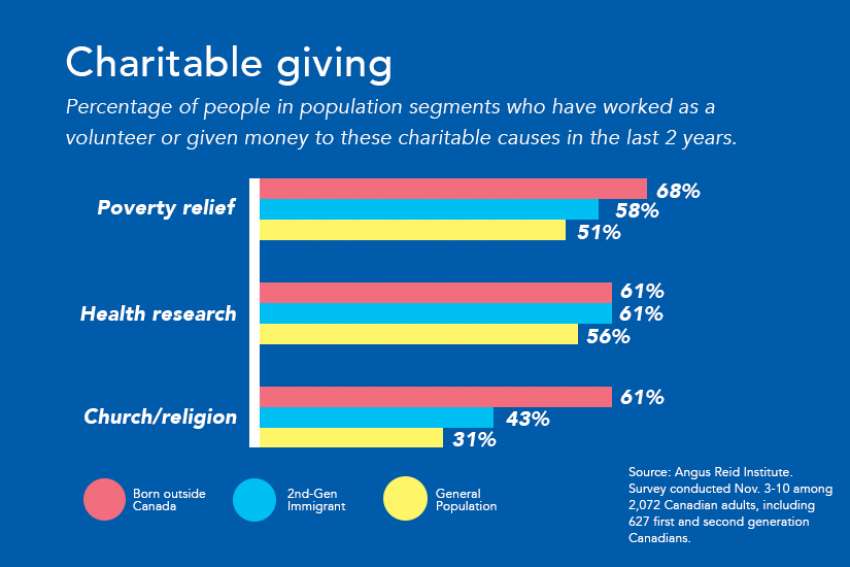

When it comes to explicitly religious or church charities, 61 per cent of those born outside Canada give, compared to just 31 per cent of long-established Canadians.

The children of immigrants (second-generation Canadians) are less generous than their parents’ generation, but still outperform the general population with 43 per cent of them supporting their church and religious charities.

“Culture and religion are big, big drivers of a strong sense among newer Canadians to give,” said Kurl. “If you are a Filipino immigrant, chances are you are Catholic and chances are you have a very strong sense of tithing.”

For ShareLife in Toronto, the loyalty immigrant donors show to their Church is a big advantage, said ShareLife executive director Arthur Peters. The one adjustment new Canadian Catholics have to make is getting used to the idea that church charity is delivered through agencies rather than directly by the bishops and priests.

“Our messaging, through our parishes and through our priests, is that we’re out there,” he said. “It’s not in the same way as the direct service they know from their countries, but we are providing service through the Church.”

Immigrants don’t concentrate their charitable activity on the Church simply out of habit, or because that’s what they used to do back home, Peters said.

“People trust the Church. There’s a high trust that the Church will use their money and be accountable in a proper way,” he said.

But Peters agrees with Kurl that raising money isn’t getting any easier.

“There’s so much competition now in the charitable sector,” he said. “There’s a lot of charities and a lot of competition.”

The Angus Reid research shows many immigrants are drawn to charities that invest directly in health care delivery or education when they want to give to an international charity, Kurl said.

“Because those speak to the basics. Health is something that affects everyone,” she said.

Over half of new Canadians (55 per cent) support international aid agencies like the Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace, compared to just 31 per cent of the general population.

Educational charities get donations from 47 per cent of immigrants but only 25 per cent of the general population. Health and disease research charities have support from 61 per cent of immigrants, but also a pretty healthy 56 per cent of the general population.

Human rights-focussed charities attract money from 27 per cent of those born outside Canada, but are even more attractive to their second-generation children who give at a rate of 33 per cent.

The old image of immigrants as needy consumers of charity who are followed by subsequent generations that gradually become donors may no longer apply, said Kurl. Today’s better educated immigrants are often contributors from day one.

“They are ready for work. They are more likely to have post-secondary training and more likely to be… perhaps in a better situation,” she said. “Largely driven by that culture of giving, again largely driven by faith, there’s also the economic ability. They can give.”

The study was conducted online between Nov. 3 and 10 among a random sample of 2,072 Canadian adults. Angus Reid cautions that because the sample was deliberately skewed to capture more South Asian, Filipino and Chinese immigrants, the results may not be applicable to all immigrants.